16 November 2018

The Digger Who Returned

Historian Dr Jacqui Donegan, from Australia’s Department of Veterans’ Affairs, explores the story of how an Australian soldier came back to France to be one of the Commission’s first gardeners.

The signing of the 1918 Armistice meant peace and a journey home for many of those who fought on the Western Front, but not everyone stayed at home. Here we’ll look back at the remarkable story of an Australian soldier who returned to France to join the Imperial War Graves Commission’s (later the Commonwealth War Graves Commission) first wave of gardeners.

These pioneers began the task the Commission continues with today to ensure its sites across the world give relatives, comrades and visitors a carefully tended space to reflect.

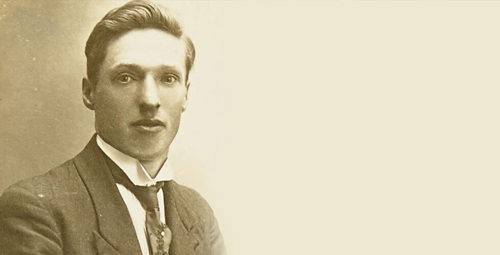

Charles Atkin was a gunner from Adelaide, who fell in love in France and, 1½ years after his repatriation, returned to live in Villers-Bretonneux and became the custodian of the Australian National Memorial.

Atkin was originally from Yorkshire, and after emigrating went to war with Australia’s 3rd Light Horse Regiment and became a driver with the 2nd Division Artillery in France.

In Villers-Bretonneux, according to his local newspaper, he ‘fell victim to the charms of a French girl’,[1] possibly while he was convalescing from a mild gunshot wound to the head. After the war he came back, married his sweetheart, Alix, and they had a daughter, Elise.

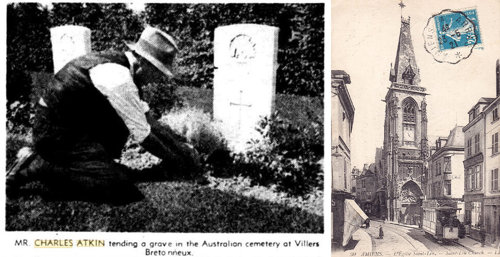

His first job was digging up shells from the war. Then, walking over the fields where thousands of his comrades had fallen, Atkin laid out the Villers-Bretonneux Memorial Cemetery and tended the beginnings of the gardens.[2]

An Australian news clipping from The News (Adelaide), 27 August 1940, during the Second World War, and One of the streets in Amiens, France where Charles Atkin lived with his family.

The ex-digger was formally employed by the Commission as a labourer and gardener, and then caretaker of the Australian National Memorial.

Commenting on the appointment, Colonel Walter Dollman said: “He was so interested in everything. He is a splendid chap, and gave us a lot of information about the war graves and what is being done.”[3]

Construction on Australia’s memorial did not begin until 1936 (delayed by the Depression), but the former dairy farmer had plenty to keep him busy.

The ‘lean and lanky Australian’ was a popular figure in Villers-Bretonneux, known as ‘Sharley’ to the locals.[4] He also remained a member of the Returned Services League in Unley, South Australia, and wrote to them about his life in France.[5] In 1932, he brought his wife to Australia to meet family and friends.

When the Australian National Memorial was officially opened by King George in 1938, Atkin was the last to leave the ceremony.

Along with French workmen and families who had built the monument in the countryside, he sat and watched as Australia’s Deputy Prime Minister Earle Page walked among the graves, and the sun set over the Amiens plateau, the white stone turning pink.[6]

Atkin was happy in Villers-Bretonneux. According to war records at the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, he fulfilled his duties with “every satisfaction … taking great interest in the work at the Memorial and being very attentive to visitors”.[7]

Two years later, when another world war swept through the Somme in 1940, and German bombers were flying overhead, he took his family to Gentelles, with their belongings in two suitcases on bicycles.

The next day he returned and met with the Deputy Mayor, Dr Jules Vendeville, who was evacuating the remaining townspeople to Cherbourg.

Germany’s airforce was blitzing Amiens and Corbie, and its troops were advancing towards Villers-Bretonneux.

“There was nothing to do but lock the memorial tower and main gate,” Atkin said.

“It was a terrible heartbreak to go. I had never seen the garden looking more beautiful.

“I did not even have time to bury the official papers or retrieve any of my own, my medals from the last war or my uniform.”

He joined seven refugees who had only a loaf and a half of bread, and slept in ditches and cowsheds, as they walked the harrowing 390km trek to Cherbourg on the English Channel.

The Atkin family escaped to London and the British Refugee Committee found Charles a job in Fulham New Cemetery, which he supplemented with factory work. His daughter, Elise, joined the Auxiliary Territorial Service, the women’s branch of the British Army.

Part of Atkin’s service record from the Commonwealth War Graves Commission.

Meanwhile, the Royal Air Force sent a reconnaissance flight over Villers-Bretonneux to determine the fate of the Australian National Memorial.[8]

It had been damaged by shell and mortar fire, as it was being used as an observation post by the French. This damage was repaired but other holes were left as honourable battle scars.

French soldiers salute the Memorial, surrounded by gardens and hay fields (AWM H17495)

Charles Atkin and his family returned to Villers-Bretonneux in 1946. He resumed his post at the Memorial and worked there until his retirement in 1961, at the age of 65. He died in 1972 and Alix lived until 1989.

Learn more about horticulture at CWGC.

[1] The Advertiser (Adelaide). 29 Jul. 1938: 6.

[2] The Mercury (Hobart). 25 Jul. 1938: 9.

[3] The Advertiser (Melbourne): 26 Jul. 1938: 21.

[4] Newcastle Morning Herald and Miners’ Advocate. 22 Oct. 1949: 5.

[5] The News (Adelaide). 26 Jul. 1938: 12.

[6] The Maitland Daily Mercury (NSW). 23 Jul. 1938: 1.

[7] F. L. Clark, Personnel Department, Commonwealth War Graves Commission, 5 Aug. 1993. Ref. P268.

[8] The News (Adelaide). 27 Aug. 1940: 4.