LIEUTENANT ALAN ALEXANDER MALCOLM AND CAPTAIN RALPH WILLIAM BELL

File reference: CWGC/8/1/4/1/2/48

Casualty Name(s): Lieutenant Alan Alexander Malcolm & Captain Ralph William Bell

Unit Nationality: Malcolm: British (born in Mauritius) Bell: Canadian unit, born in UK

Where commemorated: Arras Flying Services Memorial, France

Malcolm (left) at school, © Gresham’s School Archive.

Bell (right) from The Globe, Toronto, report detailing his disappearance

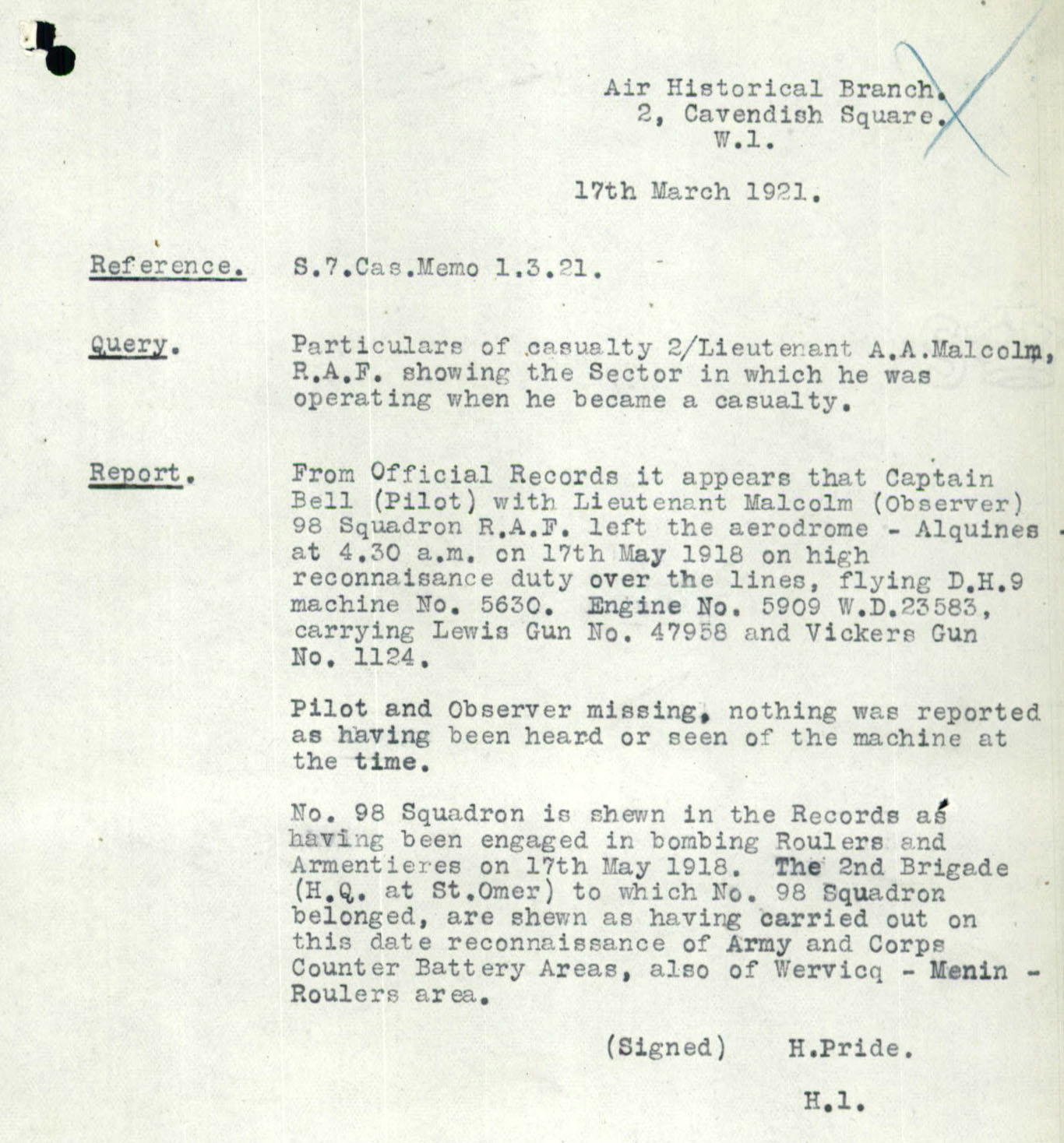

At 4.30 a.m. on 17 May 1918, Capt. Ralph Bell and his observer, Lt Alan Malcolm took off in their single-engined biplane to make a high-level reconnaissance flight over the lines in Belgium. They never returned.

It was Bell’s 32nd birthday. Born in Richmond, UK, by the time the First World War began he was married and working as a journalist in Toronto, Canada, for The Globe newspaper. He volunteered to join the Canadian Expeditionary Force within weeks of war starting, shipping out for Europe in early October 1914 with an infantry battalion. He joined the Royal Flying Corps in April 1917, training as a pilot in Reading, UK, then joining a squadron on the Western Front.

Lt Alan Alexander Malcolm, known as ‘Alec’ at school, had been 21 for three months when he climbed into their DH.9 behind Bell in the chilly, pre-dawn air. Born in Mauritius, where his father was General Manager and Chief Engineer for a forge and foundry in Port Louis, he was the eldest of three boys. By 1909 the family had returned to the UK and he and his next youngest brother were attending Gresham’s School in Norfolk, playing sprites in A Midsummer Night’s Dream.

Alec left school at Easter in 1914 to begin to train as an engineer like his father. In 1915 he joined the Cheshire Yeomanry, receiving a nomination for Sandhurst in 1916. In January 1917, the month he turned 20, he left for France with the 17th Lancers as a Second Lieutenant. Like many young men, he was fascinated by aeroplanes, and must have been excited to be accepted by the RFC to serve as an observer in October that year. Six months later, he was missing on patrol.

His squadron’s chaplain wrote ‘he was not merely a brave, gallant and keen young officer, but a thorough, out and out gentleman.’

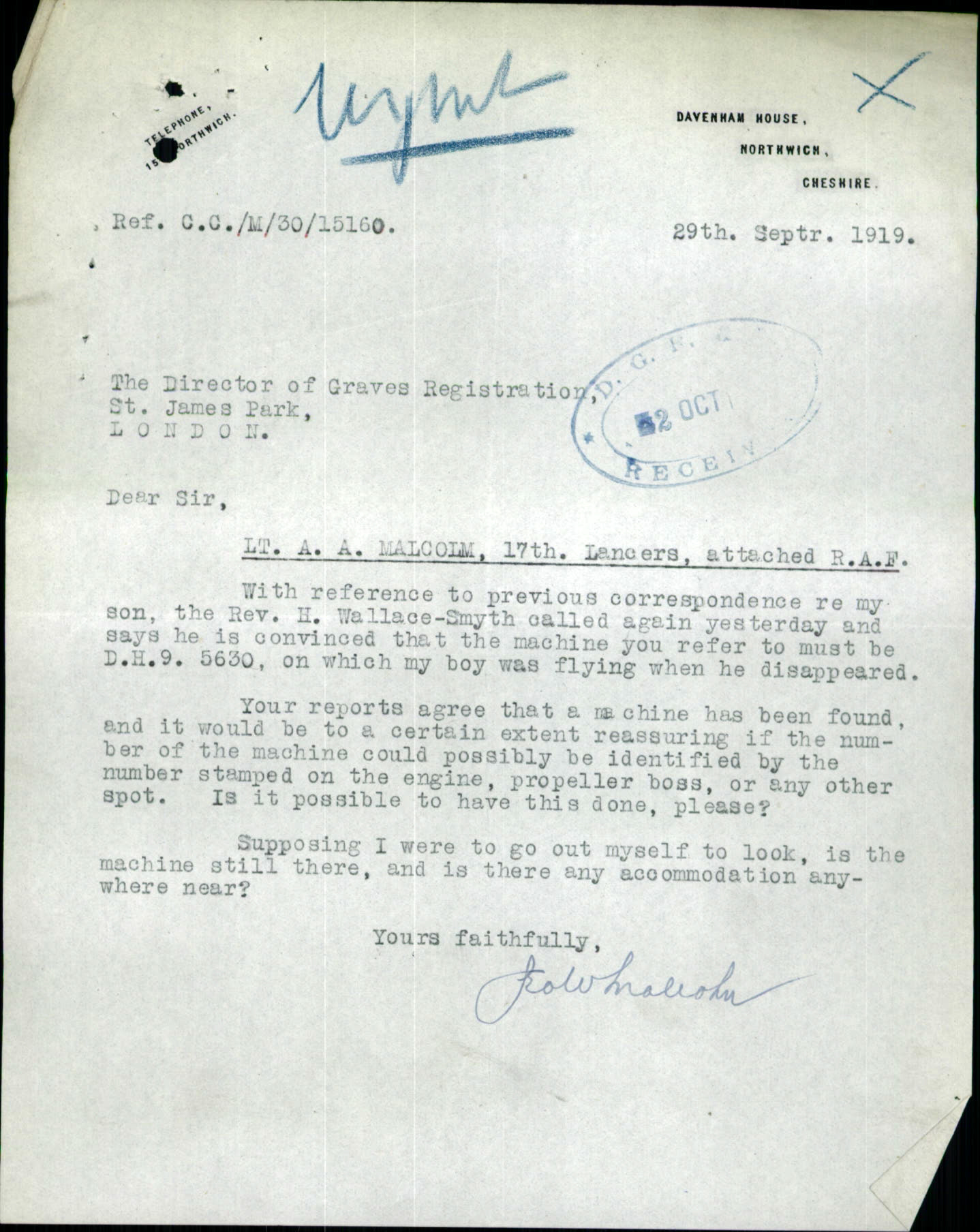

His father wanted answers.

File CCM 15160 in the CWGC archive centres around an eight-year quest by George William Malcolm, Alan Alexander ‘Alec’ Malcolm’s father, for his son’s fate and final resting place. The file contains multiple enquiries from Mr Malcolm to the DGRE as to the possible whereabouts of his son’s grave and details the DGRE’s considerable efforts to investigate the case.

Hoping to help the military authorities to find his son’s crash site and/or grave, Mr Malcolm first gets in touch in January 1919 to report information he has received about a wreck and two graves with a German-made marker saying ‘Lt Bell and his Observer’ reportedly found ‘on the Ypres-Menin Road’. The DGRE in France searched and reply that the only aeroplane wreckage that was noticed had a cross recording a different flight lieutenant’s name, and a different date for the crash.

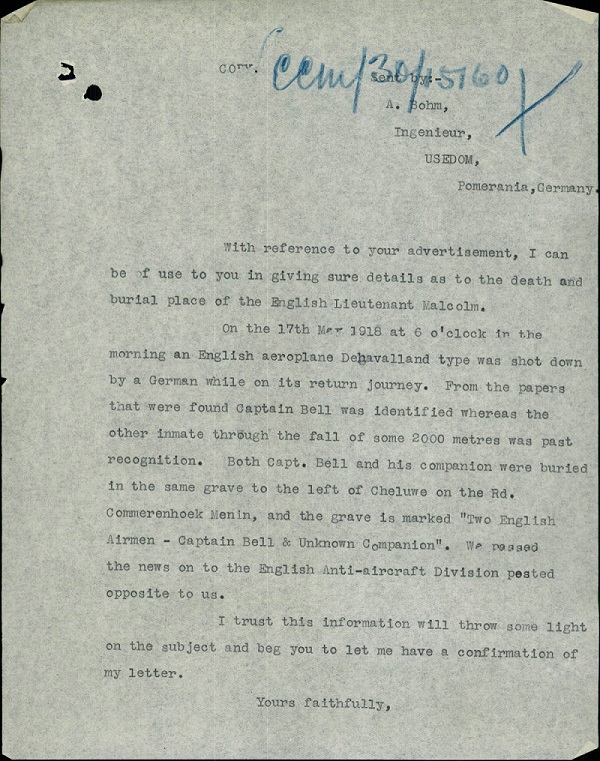

Mr Malcolm continues to look for information that might lead to the discovery of a grave for his son, and to pass any hints on to the DGRE, even placing an advertisement in the German press and forwarding on many of the letters he received from ex-soldiers claiming to have witnessed the crash or to have helped bury the bodies. Several of these speak of an aeroplane that caught fire, or crashed and caught fire; some suggest German anti-aircraft fire brought it down.

Details from some letters prompt a further search of a different potential burial location closer to Hill 60 but again, nothing is found.

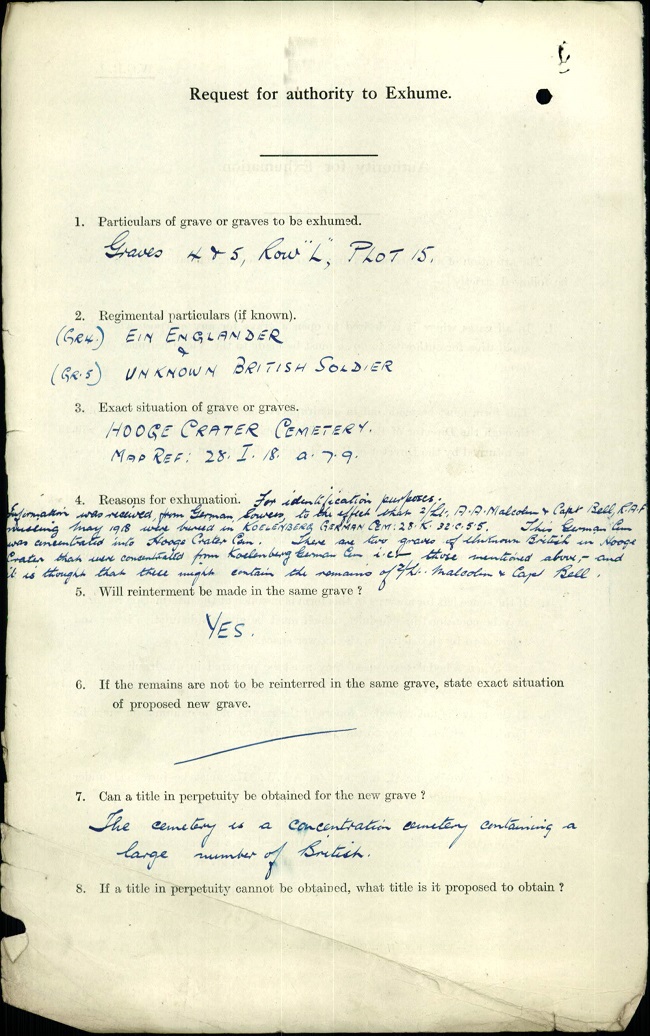

It is suggested that the graves of two unknowns in Graves 4 & 5, Row L, Plot 15 of Hooge Crater might be likely candidates. A request to exhume is made – turned down by Ware on the grounds the bodies have already been exhumed once and nothing prompting an identification was found then.

Further correspondence with a German ex-soldier (a Mr Weber) leads to a further battlefield search and a suggestion that two unknown airmen in Plot 5, Row C of Zandvoorde British Cemetery might be worth investigating. However, the aircraft serial numbers do not match and with that the Commission closes the research in October 1922. Mr Malcolm writes again in 1926, prompted by reading reports of re-interments, and once again exhumation paperwork is checked for any trace of Capt. Bell and Lt Malcolm – who would have been wearing 17th Lancers buttons – but to no avail.

The remaining correspondence details the Commission’s thought process on where to commemorate men like this and the father’s frustration at how long it takes to build the Arras Memorial. Mr Malcolm’s last letter in the file is dated 13 April 1932, asking for two tickets to the unveiling ceremony in Arras. He finally saw his son’s name carved in stone in July 1932, 14 years after the cable breaking the news that he was missing in action.