12 June 2023

An Italian expedition: Commonwealth troops at the Battle of Piave River

June 15th Marks the 105th anniversary of the Battle of Piave River – but did you know Commonwealth troops were involved in this decisive World War One event? Read on to discover their story.

The Battle of Piave River

The Italian Front

Many of the Italian Front's battles took place high in the Alps as seen from this Austro-Hungarian position some 3,000 feet above sea level (Wikimedia Commons)

Italy entered World War One on the side of the Entente Powers, i.e., France and the United Kingdom, in May 1915.

Over the next three years, Italian forces clashed primarily with Austro-Hungarian armies across a broad but varied front. Fighting occurred across Italy’s northern Alpine border in Trentino, and more mountainous terrain along the Isonzo River (today in Slovenia), as well as down the Adriatic coast.

Some of the First World War’s harshest, most brutal fighting took place in Italy. The Alpine theatre involved men clashing on snow-capped mountain peaks, in craggy, plunging valleys and ravines, and battling the elements as much as each other.

Some of the battles of the Italian campaign, pitting millions of men and thousands of heavy guns against one another, were titanic. But, like the Western Front, no significant breakthrough was achieved by either side until late on in the war.

One operation did come close to deciding the fate of the Italian front prior to Piave.

In October 1917, the Austro-Hungarian Army, reinforced by a significant number of Imperial German troops, launched the Battle of Caporetto.

This attack punched deep into Italian-held territory and threatened to knock Italy out of the war altogether. Although the attack was eventually repulsed, the cost had been very high, with Italian armies sustaining significant casualties.

Following Caporetto, the Entente committed to stepping up its military commitments to its Italian allies and reinforcing the front.

Commonwealth forces in Italy during World War One

Scottish soldiers wait on a roadside during the march to Piave River (© IWM Q 54742)

Even before Caporetto, the British Army had been sending men and materiel to the Italian front.

Ten artillery batteries from the 94 and 95 Heavy Artillery Groups had been moved to Italy in April 1917.

Given Britain had just 152 batteries in France at the time, and was fighting the bloody Battle of Arras, this marked a significant commitment.

After the events of October 1917, however, the British Army moved five divisions off the battlefields of the Western Front and transferred them to Italy. These were:

- 5th Division

- 7th Division

- 23rd Division

- 41st Division

- 48th (South Midland) Division

These units were battle-hardened, having fought at some of the Western Front’s most iconic campaigns, including the Battle of the Somme.

The British Expeditionary Force (Italy) was initially commanded by General Herbert Plumer.

Plumer might be a familiar name to scholars of Commonwealth War Graves Commission history. It was he who presided over the opening of the iconic Menin Gate in July 1927.

Image: Aircraft of the Royal Flying Corps, and later Royal Airforce, also supported the ground deployment, clashing with the limited Austro-Hungarian air force in Italian Skies ( © IWM Art.IWM ART 2677)

Image: Aircraft of the Royal Flying Corps, and later Royal Airforce, also supported the ground deployment, clashing with the limited Austro-Hungarian air force in Italian Skies ( © IWM Art.IWM ART 2677)

Indian labourers were also employed to support the logistical effort of keeping the fighting men fed and equipped at the front. Their tireless work cannot be overlooked, nor their contribution diminished.

By the time of the Battle of Piave River, two British Divisions had been sent back to France and Flanders. The 5th Division left in March 1918, followed by the 41st Division in April.

A shakeup occurred at command level too. General Plumer was reassigned back to the Western Front. He was replaced by Lieutenant General Cavan who took control of the remaining three divisions of the BEF in Italy.

Some 40,000 men, dozens of heavy artillery guns, and many aircraft formed the BEF Italy at the time of the Second Battle of Piave.

Showdown at the Piave River

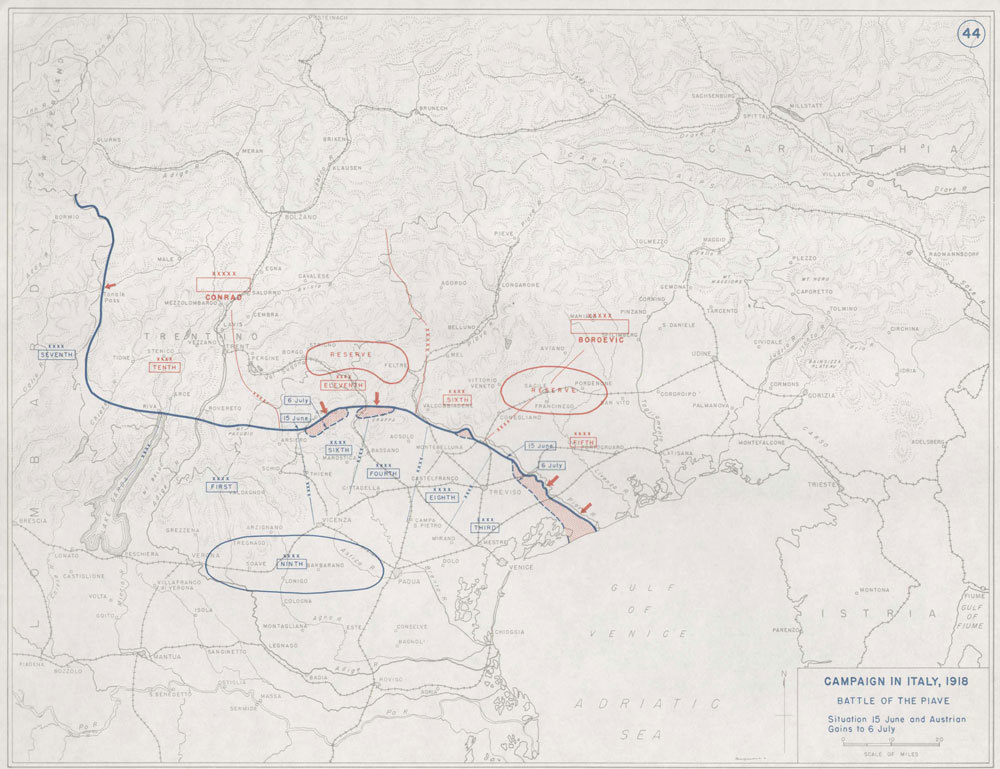

Map showing the Piave River front in June 1918 (Wikimedia Commons)

The joint Austro-Hungarian/Imperial German offensive of October 1917 had pushed the Italian forces back 100 kilometres. The new frontline in this sector lay just 30 kilometres from Venice along the broad Piave River.

Austro-Hungarian forces began to build up throughout the Spring of 1918. Soldiers were being trained and equipped to deploy breakthrough tactics similar to those used by the Imperial German Stormtroopers on the Western Front during the Spring Offensive.

The Italian Army also went through a period of reorganisation and redevelopment. General Luigi Cardona was replaced by General Armando Diaz as Chief of Staff. Under Diaz, the Italians created a more mobile force that was less constrained by rigid command structures.

As armies prepared to clash on the Piave front, the British Expeditionary Force under Lieutenant General Cavan was holding position near the small town of Asiago in rolling Alpine foothills.

Allied military intelligence surmised from the Austro-Hungarian positions an attack was possible at Brenta. By mid-May, it had become clear that the Austro-Hungarians planned to widen their front to incorporate an attack on the Piave.

The Battle of Piave River: The British at Asiago

The Battle of Piave River began on 15th June 1918.

The British divisions were involved right from the off.

Lieutenant General Cavan’s official account, written in September 1918, states the Austro-Hungarian army began their attack on the British sector at Asiago with a “short but violent bombardment”.

Four Austrian divisions hurled themselves at the British lines, which were manned primarily by men of the 23rd and 48th Divisions.

On the right flank, held by the 23rd, the Austro-Hungarians were utterly repulsed and suffered heavy casualties.

According to Cavan, things were tougher for the 48th Division. The Lieutenant General reported that Austro-Hungarian stormtroopers managed to capture the British frontline trench on the 15th of June and push the 48th Division back some 1,000 yards.

However, the ground behind the frontline had been prepared well. A series of switches and slip trenches had been dug, allowing the 48th to fall back into defendable positions along their line.

On the morning of the 16th, the 48th Division launched a ferocious counterattack. The Austro-Hungarian troops were driven back from the pocket they were occupying. By 9.00 am, the 48th Division was back in its starting position.

Dugouts along the Piave (© IWM Q 26114)

A major push by the British followed. Lieutenant General Cavan reported:

“Acting with great vigour during the 16th, both divisions took advantage of the disorder in the enemy's ranks, and temporarily occupied certain posts in the Asiago Plateau without much opposition. Several hundred prisoners and many machine guns and two mountain howitzers were brought back in broad daylight without interference.

“As soon as "No Man's Land" had been fully cleared of the enemy we withdrew to our original line.

“The enemy suffered very heavy losses in their unsuccessful attack. In addition, we captured 1,060 prisoners, 7 mountain guns, 72 machine guns, 20 flammenwerfer (flamethrowers), and one trench mortar.”

In their part of the line, the 48th Division was backed up by Italian General Monesi and the 12th Italian Division. Their men stepped up to help fill the breach left during the initial Austro-Hungarian punch through the British lines and ensured the gap was filled.

In his report of the action at Asiago, General Cavan heaped praise on the work of the Royal Air Force under Colonel P.B. Joubert.

In his after-action report, General Cavan wrote:

“The work of the Royal Air Force, under Colonel P. B. Joubert, D.S.O., has been consistently brilliant, and the results obtained have, I believe, in proportion to the strength employed, exceeded those obtained in any other theatre of war.

“Between March 10th and the present date (September 1918), 294 enemy aeroplanes and nine hostile balloons have been destroyed, and this with a loss of twenty-four machines.”

The Battle of Piave River: The Italians & Austro-Hungarians clash

Italian soldiers man a parapet (Wikimedia Commons)

The bulk of the fighting during the Battle of Piave River took place between Austro-Hungarian and Italian armies.

The Austrian army had assembled 58 divisions for the attack, around 946,000 men, backed up by over 6,750 heavy artillery guns.

Facing them were 52 Italian divisions of roughly 900,000 men. As well as the 40,000 British in Asiago, the Italian effort was supported by a further 25,000 French troops, as well as a smaller number of American units.

The Allies had 5,650 artillery pieces and 675 or so aircraft to complement their infantry.

On the morning of the 15th, the Austro-Hungarians launched their attack on the Piave across a front up to 25 miles wide.

The element of surprise was somewhat lost. Italian commander General Diaz was informed of where and when the attack would come.

30 minutes prior to the launch of the Austro-Hungarian artillery barrage, the Italians let fly with their own guns. In some stretches of the line, the Austrians were forced back to their original starting point, but the attack was kept on.

Austro-Hungarian General Svetoza Boroveić von Bojna was able to cross the Piaze on the 15th and push on down the Adriatic Coast.

Italian troops cross a pontoon bridge over the swollen Piave (© IWM Q 65289)

However, recent torrential rains had swollen the wide river, making it harder to cross. With bridges damaged or destroyed by artillery, many Austro-Hungarian units were isolated, making them easy pickings for Italian gunners.

On 19 June, the Italians under Diaz were able to sweep up Boroveić’s flank and inflict crushing casualties on the Austro-Hungarian army, forcing its retreat.

Half of the Austro-Hungarian Divisions in the Battle of Piave River had been placed under the command of General Conrad von Hötzendorf. His units were attacking the Asiago Peninsula but ran into more dogged Italian resistance.

40,000 Austro-Hungarian casualties were taken in Conrad’s attack. Conrad later drew flak from Boroveić for not halting his offensive and reinforcing the attack on the Adriatic coast.

Disconnected from their supply lines and taking heavy casualties, the Austro-Hungarians were ordered to retreat on 20th June. By the 23rd, the Italian Army had recaptured all the territory south of the Piave and ended the battle.

The aftermath of Piave River

Casualties on both sides were high during the Battle of Piave River (© IWM Q 65363)

Thoughts of launching a major counteroffensive to drive the Austro-Hungarians back over the Alps were quickly dismissed by Italian High Command.

The countryside and weather played a significant role in aiding the Italian victory. For instance, Austrians advancing down across the Piave were met with a tangled web of vineyards, country lanes and general tough country. Troop movement was difficult.

The Piave was also fit to burst and many of its bridges had been obliterated by artillery. If the Italians were to advance north of the Piave, they would meet the same logistical and transport issues that had plagued their Austro-Hungarian opponents.

Nevertheless, the Battle of Piave River was a major World War One victory for the Italians: possibly the decisive battle of the entire Italian front.

For the Austro-Hungarians, Piave was a major failure.

The once mighty Imperial-Royal Army was very nearly a spent force.

Political and societal tensions at home within the Austro-Hungarian Empire were coming to a head and that turmoil would spill over into the army’s ability to effectively operate.

The attack on the Piave River had cost the Austro-Hungarians dearly:

- 11,640 or so dead

- 80,850 wounded

- 25,550 captured

Total Allied losses came to:

- 8,400 dead

- 30,600 wounded

- 48,100 captured

The Great War in Italy would continue for several more months before one major last engagement: the Battle of Vittorio Veneto.

The British Expeditionary Force (Italy) was present at Vittorio Veneto in the same numbers as had fought at the Piave.

The attack was once again led by the Italians who smashed the remaining Austro-Hungarians in Italy and captured over 445,000 prisoners, effectively ending the Imperial-Royal Army’s ability to fight.

It wouldn’t be long before the Austro-Hungarian Empire was dissolved completely, exacerbated by significant defeats like those inflicted at Piave.

Commemorating the Commonwealth casualties of the Battle of the Piave River

Nearly 450 or so Commonwealth casualties of the Battle of the Piave River are commemorated in Italy by Commonwealth War Graves.

These World War One servicemen are primarily commemorated in four cemeteries and memorials:

- Magnaboschi British Cemetery – Approximately 125 casualties

- Boscon British Cemetery – Approximately 95 casualties

- Granezza British Cemetery – Approximately 60 casualties

- Giavera Memorial – 15 casualties

The British involvement in Italy is a little-known part of the World War One story but it is important we remember and mark the sacrifice of these men commemorated across Italy.

Lance Corporal Allen Richard Hart

Image: Lance Corporal Allen Richard Hart

Image: Lance Corporal Allen Richard Hart

The tragedy of the Great War touched families across the world and certainly the UK.

It seems every household in the country was affected by loss. Sons, brothers, husbands, cousins, and uncles were all killed or went missing during this epoch-defining conflict.

The Harts of Eastnor, Hereford were affected more than most.

Lance Corporal Allen Richard Hart was one of twelve children born to the Harts. He was also one of five Hart brothers to serve during World War One. All served with different units in different campaigns across the globe.

Unfortunately, three of the Hart brothers would lose their lives in action. In December 1916, Corporal Reginald Hart was killed serving with the Royal Field Artillery near Ypres in Belgium.

Private Sydney Joseph Hart, Allen and Reginald’s older brother, died in February 1917 in fighting at Salonika, Greece.

It was against this tragic backdrop that Allen was serving during the action as Asiago and the Battle of Piave River. He and his battalion of the 1st/7th Worcestershire Regiment were clashing with the attacking Austro-Hungarians when Allen lost his life.

Allen’s Company Commander, Captain Henry Wood, sent a letter back to his parents, which reads:

“It is with feelings of the deepest regret that I have to write to you of the death of your son. He was killed by fire from an Austrian Machine gun, while leading his section in a counterattack against the enemy on 15th June.

“It was owing to the splendid manner in which your son and his brother non-commissioned officers led their sections, and obeyed their orders, that this attack finally succeeded.

“I as his company commander, am very sorry to have lost a very promising N.C.O. Your son is buried with his comrades which fell in this action in the British cemetery close by. I should like to express the greatest sympathy of the officers, non-commissioned officers and men of the company with you in your present loss.”

Allen is today buried at Magnaboschi British Cemetery.

Discover more stories of the Commonwealth’s war dead with CWGC

Our search tools can help you uncover more stories of those commemorated by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission.

Use our Find War Dead tool to search for specific casualties by name, where they served, which branch of the military they served in, and more parameters.

Looking for a specific location? Use our Find Cemeteries & Memorials search tool to find all our sites. You can search by country, locality, and conflict.