07 October 2024

Anthems for doomed youth: Remembering the poets of the World Wars

Join us as we take a look at some of the famous war poets in CWGC’s care who sadly lost their lives in the World Wars.

Famous War Poets

War poetry

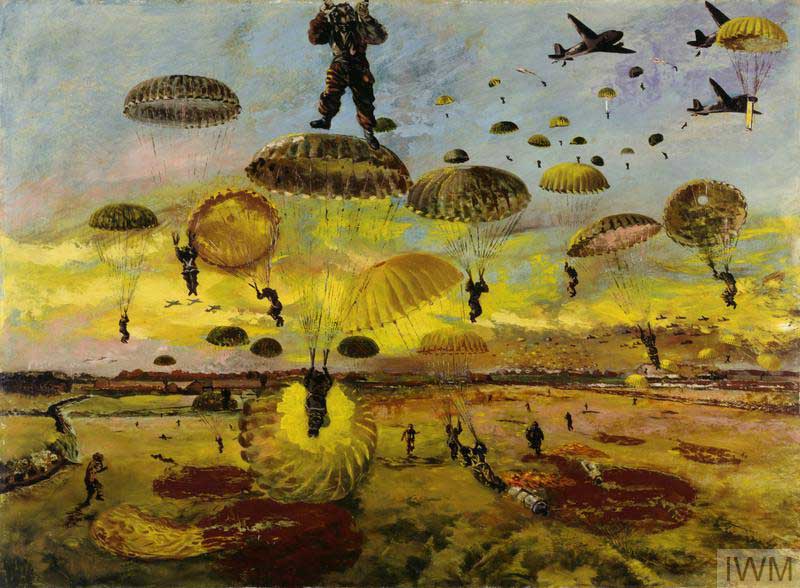

Image: In the same way the battlefields of the World Wars inspired artworks like John Singer Sargent's "Gassed", so too were the war poets inspired by their experiences and surroundings (Public Domain)

Art, literature, and warfare are closely linked.

Humanity has been recording military victories, defeats, and the general experience of warfare in a myriad of artistic mediums, since the dawn of conflict.

Some of the most enduring literature recording and commemorating the World Wars is war poetry.

Most British schoolchildren will have been exposed to the works of war poets in their education. Certainly, the likes of Siegfried Sassoon and Wilfrid Owen are household names. Their prose and verse have come to define the Western Front experience for many.

The Second World War is not so associated with war poetry as the Great War, but many talents turned their emotions and experiences into poetry during that all-encompassing conflict. Sadly, many paid the ultimate price for their service.

Those Commonwealth war poets of the World Wars who fought and fell on battlefields around the world are commemorated perpetually by Commonwealth War Graves.

Here is a small handful of some of the most famous war poets in our care.

War poets commemorated by Commonwealth War Graves

Wilfred Owen

Amongst British war poets of the First World War, several names stand out from the rest. One of those is Wilfred Owen.

His works are some of the most well-known, studied as they are in schools up and down the land. For many, Wilfred’s work is the definitive Great War poetry.

Born in Oswestry, Shropshire, England on 18 March 1893, Wilfred is said to have caught the poetry bug in 1904 during a family holiday in Cheshire.

Image: Wilfred Owen, one of the world's most famous war poets

Image: Wilfred Owen, one of the world's most famous war poets

Wilfred originally enlisted in the Artist’s Rifles, a unit featuring many of his contemporary poets, as well as painters, writers, and more soldiers from a professional art background, in 1915 but was commissioned as a Lieutenant in the Manchester Regiment after several months of training.

In the trenches, the sensitive young poet suffered several traumatic experiences that would come to shape his future work.

At one point, he suffered a concussion after falling into a share crater.

Another incident saw Wilfred knocked unconscious by a trench mortar blast. He was left exposed on a siding for several days, lying amongst the shattered remains of his fellow officers and men.

Upon being recovered from the battlefield, Wilfred was diagnosed as suffering from shell shock. He was sent to Craiglockhart War Hospital: a pioneering psychiatric centre specialising in treating the emotional wounds the Great War rent upon soldiers of all ranks.

Craiglockhart would prove a transformative experience for Wilfred.

One of his fellow patients was another of Britain’s famed war poets Siegfried Sassoon.

Sassoon, as well as several other members of Edinburgh’s literary circles, encouraged Wilfred to develop his artistic voice, focussing on the reality of life on the Western Front and the futility of warfare.

After a successful course of treatment, in which he continued to write and develop his poetry skills, Wilfred was discharged from Craiglockhart and deemed fit for light military service.

However, by July 1918, Wilfred was back on the front lines in France.

In October 1918, Wilfred was awarded the Military Cross, something he felt justified his status as a “war poet”, for gallant leadership at Jancourt. Sadly, his medal was not gazetted until 1919 after Wilfred’s death.

On 4 November, a scant seven days before the Armistice, Wilfred was killed in action crossing the Sambre-Oise Canal. One week later, on November 11, as the village bells sounded victory peals, Wilfred’s mother received notice of her son’s death.

Wilfred’s poetry has come to encapsulate one of the popular views of the Western Front: young men cut down in their droves to fuel a squabble of nations. His prose draws on the futility of warfare and the brutal nature of the First World War.

His most famous poem “Dulce et Decorum Est” pulls no punches. It describes the frenzy of an incoming gas attack, with men’s cries of “GAS! GAS!” before viscerally detailing the horrendous injuries gassed soldiers suffered.

The horrific imagery is put as a contrast to the earlier days of the war, when many young men thought service would be one big adventure, signing up full of zeal and enthusiasm, as Wilfred wrote:

If you could hear, at every jolt, the blood

Come gargling from the froth-corrupted lungs,

Obscene as cancer,

Bitter as the cud

Of vile, incurable sores on innocent tongues,–

My friend, you would not tell with such high zest

To children ardent for some desperate glory,

The old Lie: Dulce et decorum est

Pro patria mori

Wilfred Owen is buried in Ors Communal Cemetery, northern France.

John Gillespie MaGee Jr.

Image: John Gillespie Magee Jr., author of High Flight (public domain)

Image: John Gillespie Magee Jr., author of High Flight (public domain)

American John Gillespie Magee Jr. was one of a large number of young US-born pilots to volunteer with Commonwealth Air Forces, in John’s case the Royal Canadian Air Force, before the United States entered into the Second World War.

Born in Shanghai to missionary parents, turned his experiences soaring above the clouds at the controls of his warplane into some of the most vivid depictions of powered flight in literary history.

His fourteen-line paean to flying High Flight encapsulates just exactly what it was to “let slip the surly bonds of earth” and “touch the face of God”.

Describing how he conceptualised High Flight in his cockpit, Magee said: “It started at 30,000 feet and ended by the time I touched the ground”.

High Flight’s imagery is certainly evocative of the sensations of speed and powered flight far above the world below:

Oh! I have slipped the surly bonds of Earth

And danced the skies on laughter-silvered wings;

Sunward I've climbed, and joined the tumbling mirth

of sun-split clouds,—and done a hundred things

You have not dreamed of—wheeled and soared and swung

High in the sunlit silence. Hov'ring there,

I've chased the shouting wind along, and flung

My eager craft through footless halls of air...

Up, up the long, delirious, burning blue

I've topped the wind-swept heights with easy grace

Where never lark nor ever eagle flew—

And, while with silent lifting mind I've trod

The high untrespassed sanctity of space,

Put out my hand, and touched the face of God.

High Flight is, however, tinged with tragedy.

On December 11 1941, John was flying above Roxholme, Lincolnshire when, descending through the clouds, he collided with an Airspeed Oxford training vehicle. He was killed instantly, aged just 19.

Magee’s father, John, published High Flight in several church publications in tribute to his dead son. Librarian of Congress Archibald MacLeish discovered the poem and included it in his exhibition called “Faith and Freedom”, which drew significant attention to Magee's poem.

Copies of High Flight, as well as pictures of Magee, were sent to airfields across England, his words serving as inspiration to young pilots taking to the skies over Europe.

John Gillespie Magee Jr. is buried in the Scopwick Church Burial Ground. His headstone bears the words of his iconic work:

"OH I HAVE SLIPPED THE SURLY BONDS OF EARTH... PUT OUT MY HAND AND TOUCHED THE FACE OF GOD"

John McCrae

Images of blazing red poppies growing solemnly across the once war-torn fields of Flanders and the Western Front are amongst the most associated with the First World War.

Image: "In Flanders Fields" author John McCrae (public domain)

Image: "In Flanders Fields" author John McCrae (public domain)

The guns had finally fallen silent, and nature had begun to reclaim the once peaceful, rolling fields of northern France and southern Belgium with a blanket of those familiar red flowers.

Of course, this happened, but it’s the poetry of John McCrae that most evocatively brings to life the transition from battlefields to natural landscapes.

John was born in Canada on November 30, 1872. A veteran of the Boer War in South Africa, John had already seen extensive military action several years before the outbreak of the First World War.

With Canada’s entry into the war as a Dominion of the British Empire, John was one of the thousands of Canadians to volunteer for military service. A doctor by trade, John served as a Major, later Lieutenant-Colonel, and Medical Officer with the Canadian field artillery.

While tending the wounded, John saw first-hand the brutal effects of modern warfare. It must have taken quite a toll on John, as well as all those who served in the medical corps in wartime.

It is thought the death of John’s friend Lieutenant Alexis Helmer inspired him to write his most famous poem In Flanders Fields.

Lieutenant Helmer was killed in action and buried in a makeshift grave with a wooden marker. Slowly, red poppies began to grow on Helmer’s resting place, providing the catalyst for John’s work:

In Flanders Fields, the poppies blow

Between the crosses, row on row,

That mark our place; and in the sky

The larks, still bravely singing, fly

Scarce heard amid the guns below.

We are the dead, short days ago

We lived, felt dawn, saw sunset glow,

Loved and were loved, and now we lie

In Flanders fields.

Take up our quarrel with the foe:

To you from failing hands we throw

The torch; be yours to hold it high.

If ye break faith with us who die

We shall not sleep, though poppies grow

In Flanders fields.

In Flanders Fields was first published anonymously in the December 8 Edition of Punch magazine. In the magazine’s annual index, John was named as the poem’s author (although his name was misspelt “McCree”) and his fame suddenly grew.

In Flanders Fields was subsequently used for recruitment campaigns during the rest of the war.

John, however, would not live to enjoy the fruits of his potential post-war literary career. He contracted pneumonia and succumbed to the disease on January 28, 1918, and is buried at Wimereux Communal Cemetery.

Alun Lewis

Not all warfare is the intense action and combat at the frontlines. Any soldier will tell you that the short, sharp shock of fighting is interspersed with long periods of boredom and manual work.

All Day It Has Rained from the Welsh war poet Alun Lewis illuminates this, sharing the experiences of a group of comrades dealing with rainfall while training in the Welsh countryside, as seen in the poem's first stanza:

All day it has rained, and we on the edge of the moors

Have sprawled in our bell-tents, moody and dull as boors,

Groundsheets and blankets spread on the muddy ground

And from the first grey wakening we have found

No refuge from the skirmishing fine rain

And the wind that made the canvas heave and flap

And the taut wet guy-ropes ravel out and snap.

All day the rain has glided, wave and mist and dream,

Drenching the gorse and heather, a gossamer stream

Too light to stir the acorns that suddenly

Snatched from their cups by the wild south-westerly

Pattered against the tent and our upturned dreaming faces.

And we stretched out, unbuttoning our braces,

Smoking a Woodbine, darning dirty socks,

Reading the Sunday papers – I saw a fox

And mentioned it in the note I scribbled home; –

And we talked of girls and dropping bombs on Rome,

And thought of the quiet dead and the loud celebrities

Exhorting us to slaughter, and the herded refugees:

Yet thought softly, morosely of them, and as indifferently

As of ourselves or those whom we

For years have loved, and will again

Tomorrow maybe love; but now it is the rain

Possesses us entirely, the twilight and the rain.

Image: Second World War Poet Alun Lewis (public domain)

Image: Second World War Poet Alun Lewis (public domain)

Alun, who was born in Cwmaman, Wales on 1 July 1915, was a journalist, writer and poet before joining the British Army in 1940. For those who knew Alun, this may have come as a bit of a surprise as the poet had strong pacifist tendencies before enlisting with the Royal Engineers.

His first collection of war poetry Raiders’ Dawn was published in 1942 and immediately established Alun as one of the Second World War’s leading war poets.

Alun’s poetry seems to draw on the tradition set by the Great War poets as it deals with the psychological aspects of warfare as much as the physical.

He paid particular attention to the loneliness he experienced in the military, something which may seem at odds with the close comradeship experienced by soldiers in wartime.

Alun also wrote plenty of love poetry, mostly addressed to his wife Gweno.

One poem, Goodbye, details on soldier’s last night with his sweetheart before being sent away, as this extract shows:

So we must say Goodbye, my darling,

And go, as lovers go, for ever;

Tonight remains, to pack and fix on labels

And make an end of lying down together.

Alun’s military service took him to the Far East where he initially served in India until 1944 when he was transferred to Burma (present-day Myanmar).

Sadly, Alun died there on March 5, 1944. His body was found in camp near the officer’s latrines, dead from a gunshot wound to the head, his revolver in hand. Despite the circumstances the discovery of Alun’s death, a court of enquiry ruled his death had been accidental, deeming he had tripped and the shooting accidental.

Today, Alun is buried at Taukkyan War Cemetery in Myanmar.