06 June 2022

Forgotten fighters: the story of the D-Day Dodgers

British troops D-Day Dodgers wade ashore as the invasion of Sicily begins.

They were all too often overlooked but they played a major role in achieving victory in World War Two. This is the story of the D-Day Dodgers and the Italian Campaign.

The D-Day Dodgers STORY

Who are the D-Day Dodgers?

The D-Day Dodgers are the men and women of the Allies who missed the Normandy Landings on June 6th, 1944. But if you were thinking they were dodging their service, think again. Instead, they were campaigning in Italy, participating in some of the toughest battles of the European theatre of World War Two.

Why did the D-Day dodgers get this nickname?

While the name D-Day Dodgers might seem like an insult, it’s really a piece of classic British soldiers’ irony. The name came from troopers of the British Eighth Army turning an ill-advised remark from Conservative MP Nancy Astor (Lady Astor) into a cheeky song, set to the tune of soldiers’ favourite Lili Marlene.

THE D-DAY DODGERS SONG LYRICS

"We’re the D-Day Dodgers here in Italy

Drinking all the vino, always on the spree.

We didn’t land with Eisenhower

So they think we’re just a shower

For we’re the D-Day Dodgers out here in Italy."

While you can feel that classic cheeky but self-deprecating British and Commonwealth soldiers’ humour in the tune, the D-Day Dodgers experience was anything but easy. The song’s last verse cuts right to the heart:

"When you look ‘round the mountains through the mud and rain

You’ll find crosses some which bear no name.

Heartbreak and toil and suffering gone

The boys beneath them slumber on

They were the D-Dodgers who’ll stay in Italy."

Italy was a tough old gut – not the “soft underbelly” of Europe some military planners were expecting it to be. The Allies suffered roughly 311,000 casualties across the Italian campaign. Of those, 123,000 came from the multinational British 8th Army.

The men who would become the D-Day Dodgers came from around the world, including British, Canadians, New Zealanders, Indians, Australians, South Africans, and Nepalese Gurkhas. They fought alongside Polish and Free French divisions as well as Italian Royalist and even Brazilian units.

Many D-Day veterans who fought in Italy feel unfairly overlooked in the story of World War Two in Europe. It’s D-Day and Normandy that typically get the headlines. But as we’ll see, the D-Day Dodgers played a vitally important role in the defeat of fascism.

FIGHTING IN THE ITALIAN CAMPAIGN

10th June 1940. Fascist Italy and its leader, dictator Benito Mussolini, declares war on France and Britain. Cue three years of Commonwealth forces and allies battling Italian troops on land, sea, and air, concluding with victory in North Africa in early 1943.

So, what next?

British Prime Minister Winston Churchill and American President Franklin D. Roosevelt had agreed at the January 1943 Casablanca Conference that an invasion of North-West Europe would take place in 1944.

However, they were under pressure from Soviet leader Josef Stalin to help draw German forces away from the brutal Eastern Front.

However, they were under pressure from Soviet leader Josef Stalin to help draw German forces away from the brutal Eastern Front.

The next target was Italy.

On 10th July 1943. 2,600 Allied ships landed more than 180,000 Commonwealth and American troops on Sicily, kicking off the Italian campaign.

Military planners thought it might be possible for a concentrated Allied invasion to quickly knock Italy out of the war. This wasn’t the case. It would not be until May 1945 that Italy would be fully liberated.

By the end of their time in Italy, the D-Day Dodgers would have performed multiple amphibious assaults (not unlike the Normandy landings), engaged in trench warfare, fought in mud, fought in snow, and fought up and down craggy mountains and valleys.

In the end, their hard work and losses ultimately resulted in the Liberation of Italy.

Want more stories like this delivered directly to your inbox? Sign up for our newsletter for regular updates on the work of Commonwealth War Graves, blogs, event news, and more.

Sign UpKey battles of the D-Day Dodgers

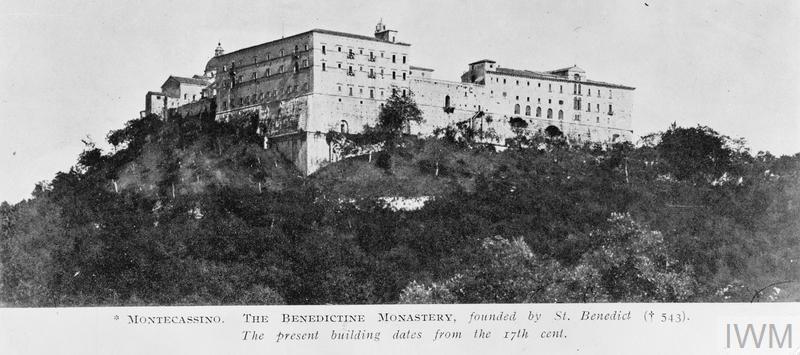

Monte Cassino

The famous medieval monastery of Monte Cassino. © IWM MH 11250

After Operation Husky and the capture of Sicily, the Allies turned their attention to the mainland. Adjacent to the Sicily Campaign, Mussolini had been arrested and overthrown, and a pro-Allied government was installed.

This triggered German forces to move into North-West Italy. During this time, Mussolini was freed from captivity by German commandos during one of the most daring raids of war and reinstalled as a puppet leader of a pro-German government in the Fascist controlled regions of Italy.

Allied landings hit the Italian mainland at Taranto and Salerno causing German forces to slowly withdraw north. They destroyed roads, bridges, and railways in their wake, slowing the Allied advance.

As part of their defensive preparations, the Wehrmacht had established the Gustav Line: a line of reinforced positions and fortifications that stretched from coast to coast.

As part of their defensive preparations, the Wehrmacht had established the Gustav Line: a line of reinforced positions and fortifications that stretched from coast to coast.

Central Italy's mountainous terrain lent itself to defence. The Germans were able to build concrete bunkers, hidden gun emplacements and lay thousands of mines across various strong points.

By December 1943, the Allied advance ground to a halt at the town of Cassino, about 70 miles from Rome.

Monte Cassino, famous for its medieval monastery, was one of the important hubs along the Gustav Line, giving its occupiers commanding views of the surrounding area. They would be able to rain fire down on any attack with ease.

Breaking German resistance at Cassino was no easy task. It would take months to dislodge them. Allied attacks started in January 1944 but would end in costly failures. A massive aerial bombardment smashed Cassino’s famous monastery on February 16th, 1944. By March, Allied bombers were attacking the town itself.

German troops were able to dig into the resulting rubble and strengthen their positions.

Operation Diadem and victory at Monte Cassino

Image: Indian Army troops advance on Monte Cassino © IWM NA 12895

Image: Indian Army troops advance on Monte Cassino © IWM NA 12895

Conditions at Monte Cassino meant the Allies had to forgo their philosophy of “steel, not flesh”. Water, ammunition, food, and supplies were ferried to the front by hand. Evacuating the wounded was especially perilous in the rubble-strewn landscape.

Following weeks and months of piecemeal attacks, Allied commanders prepared another major effort. On May 11th, Operation Diadem kicked off a concerted push to take Monte Cassino once and for all.

Powered by fresh reinforcements, the town and mountain were captured following a week of fierce combat. By the 18th of May, the Polish II Corps’ colours were flying above Monte Cassino. Allied forces linked up in the Liri Valley.

More than 50,000 Allied soldiers fell during the struggle for Cassino. Amongst their number were British, South African, Canadian, New Zealand, Polish, and Indian troops. Taking the strategic position was a truly international effort.

Cassino War Cemetery

Cassino War Cemetery sits within sight of the famous monastery.

Just shy of 4,000 casualties from the Cassino theatre are commemorated at the Cassino War Cemetery.

A further 4,000 soldiers with no known graves are commemorated at the Cassino War Memorial.

Both the war cemetery and memorial were designed by architect Louis de Soissons. The Canadian-born architect’s own wartime experience was tinged by tragedy. His 17-year-old son Philip was killed when his ship, HMS Fiji, was sunk by German bombers off the coast of Crete. Louis de Soissons would design over 40 CWGC cemeteries in Greece and Italy.

Charlie Hapeta

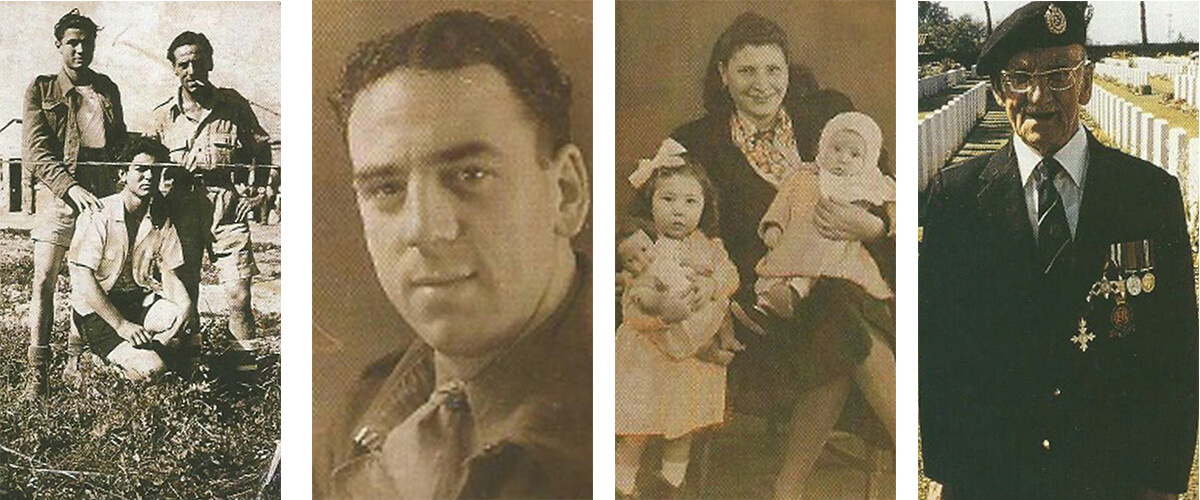

Image courtesy of Charlie's family.

Image courtesy of Charlie's family.

Charlie Hapeta was born in Okaihai, Auckland, where he lived with his wife Ngareta and four children. Charlie worked as a labourer prior to enlisting. He left New Zealand in July 1943, joining the 28th (Maori) Battalion, then serving in Italy.

The second major push to capture Monte Cassino, Operation Avenger, was launched on the night of 17/18th February 1944. Charlie and the men of the 28th Maori were at the forefront of the assault. They crossed over the Rapido River and pushed on towards the Cassino railway station.

The 28th Maori was able to capture the station after a night and a morning of heavy fighting. Support was lacking. Tank-led German attacks forced the Kiwis into retreat.

Charlie was killed during the fighting alongside 19 of his unit. He was 24 years old. He is buried alongside his fallen comrades in Cassino War Cemetery.

Anzio – another route to Rome?

Monte Cassino was proving a formidable obstacle for the Allies. To open the way to Rome, an amphibious assault on Anzio, a seaside town around 30 miles south of the Italian capital, was planned.

Operation Shingle launched in the early hours of January 22nd. Allied forces hit Anzio almost unopposed. The British 1st Division, supported by Commandos landed to the north. The US 3rd infantry, alongside the US Rangers, reached the South.

Operation Shingle launched in the early hours of January 22nd. Allied forces hit Anzio almost unopposed. The British 1st Division, supported by Commandos landed to the north. The US 3rd infantry, alongside the US Rangers, reached the South.

By midday, all of Shingle’s first-day objectives had been met. Allied commanders chose to consolidate their positions rather than keep moving. This gave time for the Germans to move eight divisions to the battlefield to potentially close the Anzio bridgehead.

An Allied breakout was attempted on January 30th. The Germans had prepared well. Concentrated mortar, artillery, and machine-gun fire held back the Allied assault. Exhausted Allied soldiers just about held onto their hastily constructed forward positions.

The Allies found themselves essentially stuck on the beach. They were fighting a battle they weren’t prepared for, defending dugouts and trenches. Men were physically and emotionally tired.

Nowhere on the bridgehead was safe from German artillery or Luftwaffe strafing runs, with the landing zone pinned. Above ground, any movement was dangerous, especially at night, as German fire intensified.

Enduring these hardships, the Allies held on, breaking through between May 23rd and 24th. 43,000 casualties were taken during the Battle of Anzio. 7,000 of those were killed in action.

Rome became the first European capital to be liberated during WW2 when Allied troops entered Rome on June 4th June 1944.

Anzio War Cemetery

Anzio War Cemetery with its antiquity-inspired architecture.

Over 1,000 casualties are commemorated in the Anzio War Cemetery. Its site was chosen not long after the landings took place. Indeed, the burials that sit within Anzio are dated from the period immediately after the Allied landings.

Like many other Italian sites, Anzio was designed by Louis de Soissons.

Eric Fletcher Waters

Eric Fletcher Waters was born in County Durham in 1914. With his wife Mary, he had two children: John and Roger. John would later become a taxi driver while Roger would find fame as one of the original founders of the rock band Pink Floyd.

Eric Fletcher Waters was born in County Durham in 1914. With his wife Mary, he had two children: John and Roger. John would later become a taxi driver while Roger would find fame as one of the original founders of the rock band Pink Floyd.

Waters, a devout Christian, initially served as an ambulance driver in Cambridge after being excused from frontline service as a conscientious objector. After joining the British Communist Party, he reconsidered, with his ardent anti-Fascist beliefs compelled him to fight.

Eric was enlisted as a Second Lieutenant with the 8th Battalion Royal Fusiliers (City of London Regiment). He and his unit were soon assigned to Italy.

On the 18th of February, Eric was killed in fighting at Anzio. His body was never recovered. His name is commemorated on the wall of the Cassino Memorial. His wartime experience would provide major inspiration for his son Roger’s music, especially the song When the Tigers Broke Free, which was written about his death.

Legacy of the D-Day Dodgers

Two days after the D-Day Dodgers liberated Rome, Operation Overlord began.

But while the world focuses on the anniversary of D-Day in Normandy for another year, we must not forget the hundreds of thousands of men who fought and died in the Italian campaign.

They were the D-Day Dodgers and they’ll stay in Italy.

Learn more about D-Day WW2 memorials.

Support our work to keep their memories alive

As the Second World War fades from living memory, it's never been more important to keep the legacies of those who gave their lives in this world-changing conflict alive. You can help us do that by supporting the Commonwealth War Graves Foundation.

Support our work and help honour the 1.7 million who never returned home

Author acknowledgements

Alec Malloy is a CWGC Digital Content Executive. He has worked at the Commonwealth War Graves Commission since February 2022. During that time, he has written extensively about the World Wars, including major battles, casualty stories, and the Commission's work commemorating 1.7 million war dead worldwide.

This blog was written with the help of Nick Bristow. Nick is a CWGC Historian who has worked for the CWGC since 2012. For the past five years as worked on the Commission Non-Commemoration Project having previously worked for the Archives and Records departments, and in support of the CWGC’s centenary and anniversary events.

He has contributed to research and published material, as well as given talks, tours, and presentations, on a wider range of topics covering the Commission’s work, history, the casualties we commemorate as well as many aspects of the world wars.