24 April 2025

In their footsteps: An emotional journey around the cemeteries of Gallipoli

In 2024, CWGC staff member Harvey Henson embarked on an eye-opening trip to the cemeteries and memorials of the Gallipoli Campaign.

Visiting the Cemeteries & Memorials of The Gallipoli Campaign

An introduction to Harvey

Image: Harvey, posing with the CWGC Torch for Peace

Image: Harvey, posing with the CWGC Torch for Peace

My interest in Gallipoli first arose when reading Lyn MacDonald’s spectacular book, ‘1915: The Death of Innocence.’

Despite studying the First World War for over ten years and having a strong understanding of the Western Front through research and visiting the battlefields, I admittedly knew nothing about the action which took place at Gallipoli.

Quickly, I was hooked with discovering the history of this campaign, and I was taken aback by the story I had overlooked for so long.

Sometime later, I discovered I had a relative, Arthur Spooner, who had been killed in 1917 whilst fighting around Ypres with the 11th Lancashire Fusiliers, aged 19.

Although this battalion never fought at Gallipoli, Arthur’s additional information on the CWGC database says, “Also served at Gallipoli. Twice wounded.” To this day, I am yet to uncover where and when he fought in Gallipoli, however, he would have been just 17 at the time.

After a few months of research, I was beginning to understand the campaign, and there was only one thing left to do: visit the Gallipoli Peninsula.

The Gallipoli Peninsula is South-West of Istanbul on the European side of Turkey, To the right of it is the Dardanelles, which is the entrance point to the Sea of Marmara. The Bosporus runs through Istanbul into the Black Sea.

A brief History of the Gallipoli Campaign

The Landing 1915, George Lambert, 1922 (Wikimedia Commons)

By the end of 1914, it was clear that a swift victory on the Western Front would not be possible, and the British had lost over 44,000 men by the 1st of January 1915.

In addition, the Russians were fighting a vicious war on the Eastern front, and it was decided that a naval expedition to the Dardanelles would open a passage to the Black Sea to allow shipping routes to and from Russia and also knock the Ottoman Empire out of the war.

Initially, the capture of the Dardanelles was to be a solely naval operation. Following minor operations at the beginning of the year, an Anglo-French fleet sailed into the straits on the 18th of March 1915.

They were met with fierce resistance from Turkish coastal defences and encountered minefields which saw the loss of three warships. The attack was soon abandoned.

Following the initial failed naval attack, plans began to be put in place for a combined naval and military operation.

However, all elements of a surprise had now been lost, and the German general Liman Von Sanders who had been appointed command of the Turkish 5th Army, which defended the peninsula, made use of the time to improve coastal defences at the obvious landing beaches.

The southern tip of the Gallipoli Peninsula was to be attacked by the British 29th Division and the Royal Naval Division, who would land at five beaches, codenamed Y, X, W, V and S beaches in the Cape Helles area.

The Australian and New Zealand Army Corps (ANZAC), alongside the 29th Indian Brigade were to land on the western side of the peninsula, at Ari Burnu beach, which would later be immortalised as Anzac Cove.

The 1st French Division which comprised largely of colonial soldiers was to land on the Asian side of the Dardanelles at Kum Kale in a partly diversionary attack.

In the early hours of the morning on the 25th of April 1915, a force of almost 75,000 men began to disembark from troopships and row towards the shores of Turkey. They almost immediately met fierce resistance from the Turkish defenders as they fought inland through an arid environment.

On the first day of the campaign, the Commonwealth forces would suffer 1423 deaths, alongside thousands more missing and wounded.

Image: Australian servicemen on the offensive during the Gallipoli Campaign (© IWM Q 13685)

At Cape Helles, the British divisions fought off the beaches and established a foothold on the southern tip. In the ANZAC sector, the Australian and New Zealand soldiers fought gallantly up the rugged steep slopes of the Sari Bahr range to establish a line which would remain largely unchanged for the entirety of the campaign.

The fighting at Gallipoli quickly descended into stalemate, not dissimilar to that on the Western Front. For 8 months, allied forces would occupy areas of the peninsula, living in extremely harsh conditions with scarce water supplies, vicious fighting and disease, whilst seeing very limited progress made.

Despite almost incessant and gallant attempts to advance, the Turkish defenders held on, and on the 22nd of November, it was decided that the Gallipoli Peninsula would be evacuated.

The withdrawal was meticulously planned, and on the 9th of January 1916, the last allied soldiers left the peninsula, leaving behind over 36,000 of their comrades who lost their lives in the campaign.

The Imperial War Graves Commission’s early work in Gallipoli

Throughout the Gallipoli campaign, various cemeteries were established behind the lines to bury those who had lost their lives. However, following the evacuation of the peninsula in January 1916, very few Allied representatives would return until after the armistice in November 1918.

Due to this, upon returning to the peninsula post war, the Graves Registration Unit’s and the IWGC were presented with a series of unique challenges when identifying the war dead and with the designing and construction of permanent cemeteries and memorials.

In May 1919, IWGC Architect Sir John J Burnet visited the Gallipoli Peninsula and reported back with his findings, and his recommendations for the commemoration of the war dead.

In his report, he wrote that the “work of the G R & E has been rendered very difficult owing to the occupation of the country by the enemy since the evacuation in 1916. New trenches and roads have been formed and graves disturbed.”

He further remarked that “the lack of complete and correct official records of the fallen has rendered the search there more widespread and the results less definite.”

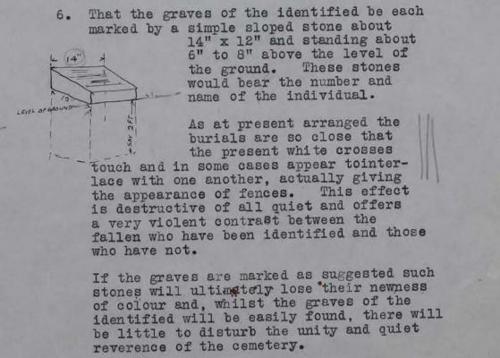

Image: Gallipoli Marker design note (CWGC Archive)

Furthermore, the geology and landscape of the peninsula was immediately obvious as a difficult challenge for building structures. John J Burnet wrote that:

“We found this particularly the case in the Anzac area where hills rising practically from the coastlines to a height of from 100 to 260 feet are drained by valleys barely 1 mile in length. These hills seem to be entirely composed of layers of sand and gravel, and although in certain places they stand almost vertical they exhibit - particularly in the Northern section of Anzac, Shrapnel Valley, the Sphinx and below Walker's Ridge - traces of extensive landslides which, though covered at the time of our visit with a rough scrub, indicate in my opinion unreliable and insecure ground unsuitable as foundations for permanent monuments of any size or weight.”

It was during this visit that John Burnet designed the pedestal-style headstone, known as the ‘Gallipoli marker,’ which would become synonymous with the cemeteries on the peninsula as seen in the sketch above. This style of headstone was far more suitable for the ground conditions.

Maps drawn of cemeteries during the campaign generally identified the location of a burial, but not who had been buried. As a result, vast amounts of burials are unidentified.

The decision was made not to mark the graves of unknown servicemen with “Known Unto God” graves like one would see elsewhere on the Western Front. Where the information of someone buried in a site was recorded, but their exact burial location was lost – special memorials for those “Known to be buried in this cemetery,” were erected.

Sir John J Burnet was the principal architect tasked with designing the cemeteries and memorials in Gallipoli.

The Visit – ANZAC Sector

On our first day, we prepared for a day of exploring the battlefields with a traditional Turkish breakfast and coffee on the waterfront of Gelibolu, which was enjoyed whilst looking directly down the Dardanelles, towards the Canakkale 1915 bridge and beyond. The bright November sun beamed down onto the calm seas, lighting the surrounding hills and towns which shroud the passage of water.

Despite the peaceful nature of our surroundings, one could only begin to imagine the sense of fear, urgency and confusion that the locals of the town whose footsteps we walked in must have felt as a fleet of Allied war ships attempted to force their way through the Turkish defences in March 1915.

Our first day was to visit the cemeteries and memorials in the ANZAC sector, on the western side of the peninsula, where Allied and Turkish cemeteries run along the length of the Sari Bahr ridge, and in many places perfectly mark the limit of the ANZAC advance in this sector.

As you drive along the winding roads which snake along the coast of Gallipoli, the steep, rugged and scrub-laden cliffs begin to creep up and tower above you, offering the first indication of just how difficult the terrain the Allied forces faced.

Turning onto the road which runs along the length of the high ground in the Anzac sector, you quickly ascend and whilst the thick forests which cover the slopes are difficult to see through, you begin to catch the first glimpses of ANZAC Cove, and soon the distinctive obelisk of the Lone Pine Memorial reveals itself in the distance. This was to be the first stop of our trip.

The Lone Pine Memorial commemorates 4900 Australian servicemen who died during the Gallipoli campaign and have no known grave. The attached cemetery is the final resting place for 1167 men, of which 504 are unidentified.

Like many who visit Commonwealth War Graves Commission cemeteries, one can spend lots of time walking through the rows of headstones, reading the names of those who fell, and one in particular might stand out for no apparent reason.

For me, that was the grave of Private Cyril Lindsay Reid, who lost his life on the 25th of April 1915.

Image: The grave marker of Private Cyril Reid

Cyril was an electrician pre-war and enlisted into the 7th Battalion Australian Imperial Force (AIF) on the 8th of September 1914 at aged 24.

Cyril’s older brother, Mordant Leslie Reid, would also serve as a Lieutenant in the 11th Battalion Australian Imperial Force (AIF) and would also lose his life on the 25th of April 1915. Mordant is commemorated on the Lone Pine Memorial, overlooking his brother's grave.

The area which Lone Pine Cemetery and Memorial sits on was once at the very heart of the fierce fighting that took place, and much of the area around it has been preserved so that visitors can walk the trenches which still scar the earth, 110 years later.

After leaving Lone Pine and continuing along the road, we were quickly met by Johnston’s Jolly Cemetery, a much smaller battlefield cemetery which contains the graves of 181 servicemen, of which just 36 are identified.

It was here that one is able to see just how different the cemeteries in Gallipoli are to those elsewhere in the world, as the graves of those 145 unidentified soldiers are not marked, so much of the cemetery is a beautiful green lawn.

Among the graves is the final resting place of Private Thomas Henry Reeves, who was killed in the area on the 7th of September 1915, aged 23.

Image: Johnston's Jolly Cemetery

Along this road, there are many cemeteries which, as previously mentioned, often sit at the furthest points of advance in the ANZAC Sector.

On this day, we also visited Coutney and Steele’s Post, and Quinn’s post, both of which are smaller cemeteries with many unidentified burials. Quinn’s Post Cemetery offers an exceptional view along the ANZAC sector coastline.

Our next stop took us to Beach Cemetery, which is located next to Anzac Cove, and was one of the cemeteries used extensively throughout the campaign. The casualties here were better recorded, as there is a higher proportion of identified graves.

Image: Private Frank Vivian Searle's grave marker overlooking the sea

Image: Private Frank Vivian Searle's grave marker overlooking the sea

The cemetery is beautifully tended and peaceful despite the waves crashing into the shore below. The placement of headstones is a window into the chaotic nature of life behind the lines, and the cemetery contains the graves of 371 servicemen, of whom 22 are unidentified.

Inscribed into the altar are the words “The Australian & New Zealand Army Corps Landed Near This Spot at Dawn on April 25th, 1915.”

Of the many deeply moving personal inscriptions which offer a glimpse into the grief felt by those who lost their loved ones, one particularly stood out to me. That was of Private Frank Vivian Searle, who served with the 12th Battalion AIF, and was killed by a rifle bullet on the 30th of August 1915.

His inscription was chosen by his mother and reads “Our Anzac, his life so pure and gentle and his death so brave and grand.”

Continuing along the coastal road, a wooden CWGC sign pointed into the scrub. We parked and began to walk along of the path where the incredible Shrapnel Valley Cemetery revealed itself.

Shrapnel Valley is on the slopes of the Sari Bahr Range, and was named after the extensive Turkish artillery which fell on soldiers in the valley on the 26th of April 1915. It was used as a key route to the front lines, a camp and a depot.

Image: Shrapnel Valley Cemetery

The cemetery is nestled into the valley, surrounded by the dense shrubbery that conceals steeps sides which was once home to thousands of soldiers during the campaign. There are 683 servicemen buried in this cemetery, and the gaps in the rows indicate the final resting place of the 85 men who are unidentified.

To the left of Shrapnel Valley Cemetery, a sign points to a small track which is the only access route to Plugge’s Plateau cemetery. The path is around 500 metres, and with each step, the views of ANZAC Cove and beyond become clearer and clearer.

The sun was setting at this point, and rays of light slipped through the clouds and lit up Shrapnel Valley, Anzac Cove, and the glistening sea beyond.

Image: Plugge's Plateau Cemetery, ANZAC

Plugge’s Plateau was a flat area on the slopes of the Sari Bahr Range, named after Colonel A Plugge, who located his headquarters there. It was used as a battery position and a reservoir, and it was likely a site of early battlefield burials.

This cemetery in an isolated, quiet pocket of the Gallipoli battlefields is the final resting place of 17 identified men and 4 unidentified.

One of these men is Private Sydney Smith of the 6th Battalion AIF, who lost his life during the initial landing on the 25th of April 1915.

Image: The now peaceful ANZAC Cove

The final stop of our first day was to be Ari Burnu Cemetery, which is located on the opposite side of ANZAC Cove to Beach Cemetery.

Image: The sun sets on Ari Burnu Cemetery, next to the wine-dark Aegean Sea

In the backdrop of the cemetery, the steep cliffs which the ANZAC troops desperately fought up following the landing tower over the cemetery, and the sea crashes around you, yet as the sun began to disappear behind the Aegean Sea, it was a beautiful resting place for 252 servicemen.

Day 2 – Cape Helles

Image: The many names inscribed on the Cape Helles Memorial

Image: The many names inscribed on the Cape Helles Memorial

Our second day in the Peninsula took us to the southern tip of the Gallipoli Peninsula, where soldiers of the British 29th Division and the Royal Naval Division landed at five beaches on the 25th of April 1915.

During the landings, these divisions suffered heavy casualties, particularly at V and W beaches, due to the cliffs surrounding them being heavily defended.

The landscape in this area is much flatter, far less rugged and is largely agricultural land with small towns dotted around. Leaving the coastal paths and driving across country, it is clear to see the challenges faced by the soldiers fighting in this area where control of high ground offered the Turkish defenders great observation.

The first stop was the Cape Helles Memorial, a 100ft obelisk which towers over the surrounding area, and lists the names of nearly 21000 British, Indian and some Australian soldiers who have no known grave.

Its location means it is visible for many miles by the thousands of ships which sail through the Dardanelles each year and it serves also as a memorial for the campaign in its entirety.

The outer wall is engraved with the names of the missing, and we took our time to read them, occasionally looking up to admire the undisrupted view of the surrounding battlefield.

Down the hill from the Cape Helles Memorial is the remains of the Ertugrul Baston, a prewar fortification that despite being bombarded prior to the landings, proved to be a formidable defensive position.

To the left of the fort, there are reconstructed Turkish trenches where one can see ‘V’ beach in its entirety. It was at this beach that the SS River Clyde, a collier refitted as a landing craft, was intentionally run aground with 2000 men of the 2nd Hampshire Regiment, 1st Royal Munster Fusiliers, the 1st Royal Dublin Fusiliers and a Royal Engineers company onboard. The remaining men of the 1st Royal Dublin Fusiliers rowed to shore in small boats.

Image: 'V' Beach from the Ertugrul Baston. Can you spot the CWGC cemetery in the distance?

Initially, the landing appeared to be unopposed. However, as the SS River Clyde was grounded, they came under heavy machine gun, rifle and artillery fire from the Turkish defenders who were situated at the fort we were stood at, and from the Sedd-el-Bahr Fort to the left of the beach.

Very few of the men on the SS River Clyde were able to disembark during daylight, and it was remarked that ‘V’ beach was red with blood. It was not until night fell that the remaining men of the Dublin’s, Hampshire’s and Munsters were able to successfully capture the village of Sedd-el-Bahr and the forts surrounding it.

Our next stop was V Beach cemetery, and to access the site, one must walk the length of the beach. It is no more 10 metres across, with a low bank which once the only refuge to those who had managed to get to shore, however, today there are very few reminders of the fierce fighting which occurred. In the gaps between waves crashing to shore, there is little to disrupt the peace.

Image: War graves lie peacefully next to the Aegean's lapping waves at 'V' Beach Cemetery

V Beach Cemetery is a larger site, and its vast open space has rows of neatly arranged headstones, and scattered graves which are dotted around.

Despite burials taking place here early in the campaign, it is clear that the records of where, and who was buried did not survive.

The rows of headstones are special memorials for those who are known be buried in the cemetery, and the individual graves are for the few whose exact burial location is known.

One of these graves is of Major John Henry Dives Costeker, who was killed in an attempt to disembark the SS River Clyde.

V Beach was exceptionally atmospheric, and as I sat book in hand reading the accounts of what had occurred on the beach, I was overwhelmed by the horrific ordeal which had faced the men who are buried in the site. It is the final resting place of 696 servicemen, of which 480 are unidentified.

Further up the beach, the remains of the Sedd-el-Bahr Fort which was heavily damaged by naval bombardments, has been preserved as a museum. It is a fantastic place to learn about the campaign from a Turkish perspective, and it also offers views along ‘V’ beach.

Despite the extensive destruction of this fort from naval bombardments, the Turkish defenders were able to inflict heavy casualties on the allied attackers from this position.

Image: Lancashire Landing Cemetery

From ‘V’ Beach, we drove up to the coast to Lancashire Landing Cemetery, which sits on the cliffs above ‘W’ Beach.

Here, I was able to visit Captain Thomas Bower-Lane Maunsell of the 1st Battalion Lancashire Fusiliers who is commemorated on my local war memorial. Thomas lost his life on the 25th of April 1915, and his story can be read on For Evermore, the CWGC stories archive.

Lancashire Landing Cemetery has 1237 burials, of which 135 are unidentified. ‘W’ Beach, now known is as ‘Lancashire Landing beach’ is a small beach, shouldered by cliffs on each side which were laden with trenches and machine gun posts.

On the beach, there were thick belts of barbed wire to prevent attackers from getting off the beach. As Allied soldiers began to land on ‘W’ beach, they were immediately met by machine gun and rifle fire from the cliffs on each side of the beach, and suffered heavy casualties.

It was remarked that “the men were mown down as by a scythe” as they waded to the shore. Many men were hit in the boats before they could reach the beach.

Throughout the day, the 1st Battalion Lancashire Fusiliers managed to fight their way off the beach despite strong resistance from the Turkish defenders, at a huge cost. The battalion famously won ‘6 Victoria Crosses before breakfast' for their gallant fighting on ‘W’ beach.

Image: 'W' Beach as it is today

Our next stop were the in-land cemeteries in the Cape Helles Area, which were built on the sites fought over as the allied made limited advances in this sector, including Pink Farm, Twelve Tree Copse, Redoubt and Skew Bridge Cemetery.

Nestled away in remote corners of agricultural land, these cemeteries are largely surrounded by tall pine trees which create an oasis of tranquillity among the flat landscape.

The contrast between luscious green integrated into the horticulture and surroundings paired with the bright white cemeteries really is a spectacle.

Image: War graves lie beneath verdant greenery at Twelve Tree Copse cemetery

At the time of building cemeteries and memorials, the New Zealand government wanted their men who had to known grave to be commemorated close to where they fell, so there is a memorial to the missing at Twelve Tree Copse Cemetery which commemorates nearly 180 New Zealand soldiers who are missing.

In addition, Twelve Tree Copse is the resting place of 3360 servicemen, of which 2226 are unidentified.

As the name suggests, the cemetery has twelve trees dotted around, and its amphitheatre design lets you view the cemetery from many different perspectives and angles.

Pink Farm Cemetery is of a similar design, and as you ascend the site, one can see the landscape for many miles, towards the Turkish memorial, and the Dardanelles beyond.

Image: The many Gallipoli markers at Pink Farm Cemetery

Redoubt Cemetery was particularly striking due to its vast open lawn, which is surrounded by a neat margin of special memorials for those known to be buried at the site.

Like many of the cemeteries, in Gallipoli, it is quite hard to fathom that this is not just empty space, but rows upon rows of unmarked graves. There are 2027 burials at this site, of which 1393 are unidentified.

A lone reddish eucalyptus tree stands in the middle of this area, contrasting with the green and white tones of the cemetery and its surroundings.

Image: The lone red eucalyptus tree stands sentinel over the war graves at Redoubt Cemetery

Our final visit for the day was the Turkish Martyrs Memorial, a colossal structure which commemorates the Turkish forces who lost their lives during the campaign.

Its four pillars tower far above and can be seen from many points in Cape Helles. It is a must-see site for any visitor to Gallipoli.

Image: The sun sets behind the moving Turkish Martyrs Memorial

Day three – Returning to ANZAC

On our third and final day on the peninsula, we returned to the ANZAC sector to visit the cemeteries around the peaks of the Sari Bahr range, including Baby 700, and Chunuk Bair Cemetery and Memorial.

Chunuk Bair was one of the two peaks on the range which was attacked on the 7th of August 1915 and was a position which dominated the surrounding area, with clear views towards Anzac Cove, and the Dardanelles. Just two days later, the Turkish forces recaptured the position, and it would remain in their hands until the end of the campaign.

Chanuk Bair cemetery has 632 burials of which a mere 10 are identified. From the cemetery, the views are astounding, and one can only imagine how those allied forces must have felt as they stood here and caught there first glimpse of the Dardanelles beyond.

Image: War markers downhill from the Chunuk Bair Memorial

Below Chanuk Bair, The Farm Cemetery sits on the hillside. Unfortunately, in August 2024, wildfires swept through much of the ANZAC sector, which affected many cemeteries.

The CWGC team based in Gallipoli have done an astounding job at restoring the sites, which among the apocalyptic surroundings continue to be a place of peace and reflection.

This can be seen at The Farm Cemetery, and many which sit along the coast of the ANZAC sector. The Farm Cemetery has 654 burials, with just 7 identified burials which sit in a row at the top of the cemetery. The below cemetery plan shows the extent of the unidentified burials

Image: Cemetery plan of The Farm Cemetery (CWGC Archive)

Having explored the many cemeteries which sit on the high ridges, time was unfortunately beginning to run out, we headed down the hills back onto the coastal road in the ANZAC sector, which runs parallel to multiple cemeteries, all of which were affected by the recent fires.

These included Outpost No 2, Canterbury, 7th Field Ambulance and Embarkation Pier Cemetery, all of which are beautiful sites that despite being damaged by fire, have been cleaned and restored perfectly.

Image: One of the restored cemeteries in Gallipoli, brought back to life after suffering devastating fire damage

Image: One of the restored cemeteries in Gallipoli, brought back to life after suffering devastating fire damage

As the sun began to set on our final evening visiting the Gallipoli Peninsula, we walked the shores of ANZAC Cove and reflected on our trip.

I felt so humbled and privileged to walk in the footsteps of the many thousands of Allied soldiers who fought in the campaign 110 years ago, and those who never left the peninsula. Gallipoli is an incredibly moving place to visit, and I would encourage anyone to visit if they get the opportunity.

Explore your family history with Commonwealth War Graves For Evermore Tour

![]()

If you're like Harvey and have family that served in the World Wars and are commemorated by Commonwealth War Graves, join us for the For Evermore Tour: an exciting nationwide interactive exhibition.

Come and join us as we mark the 80th Anniversary of VE and VJ Day to learn more about your family, local, and national history. We've thousands of moving, inspirational, and stirring casualty stories - and we can help you discover and tell your own.

Visit our VE Day 80 to learn more and find all our events happening near you!