04 March 2024

Legacy of Liberation: The True Story of The Great Escape

80 years ago, one of the most remarkable events of the Second World War. Discover the true story of the Great Escape with Commonwealth War Graves.

The Great Escape WW2

48 names in Poznan Old Garrison Cemetery

Image: The peaceful garden-like Poznan Old Garrison Cemetery

Poznan Old Garrison Cemetery sits in the heart of the historic city of Poznan, Poland, tucked amongst civilian burial grounds in the city’s verdant Citadel Park.

Some 448 Commonwealth burials of the First and Second World Wars lie within, victims of the air war over Germany or prisoners of war who died in captivity.

But within the ranks of the buried WW2 POWs at Poznan, you’ll find 48 names that stand out from the rest; 48 men who, one night in March 1944, were involved in one of the most storied, audacious escape attempts in the history of warfare: the Great Escape.

What was The Great Escape?

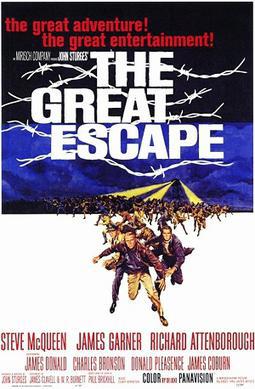

Image: Poster of The Great Escape film. Released in 1963, it was based off the incredible events at Stalag Luft III in March 1944 (Wikimedia Commons)

Image: Poster of The Great Escape film. Released in 1963, it was based off the incredible events at Stalag Luft III in March 1944 (Wikimedia Commons)

The Great Escape was World War Two's largest breakout from a German prisoner of war camp.

The event took place on 25 March 1944, 76 POWs of Stalag Luft III camp escaped captivity.

Through meticulous planning, preparation and clever deception, the prisoners were able to outwit their captors but ultimately the Great Escape ended in tragedy, as the 48 escapees buried at Poznan Old Garrison Cemetery can attest.

The Great Escape has become immortalised in film, with the 1963 Steve McQueen and Richard Attenborough starring movie becoming a staple Christmas and bank holiday for a certain UK generation.

But here we go beyond coolers, motorbikes, and baseballs to tell the real story behind the Great Escape.

Prisoners of Wars in the Second World War

Capture

Image: Commonwealth soldiers are led away after being "put in the bag", North Africa crica1941-1942 (© Alamy)

Despite the tide beginning to turn thanks to victories in North Africa and the invasion of Italy, much of Europe remained under Nazi German occupation by 1944.

Tens of thousands of Commonwealth service personnel were taken captive in wartime, captured after battles, shot down over enemy territory, washed ashore following vessel sinkings, caught on espionage missions, and a myriad of other reasons.

For soldiers, being caught and put “in the bag” was often a humiliating experience. Service personnel went from being warriors to captives.

POWs were protected by the 1929 Geneva Convention. Breaking its terms was a war crime. Prisoners who gave their true name and rank gave their captors a duty to have care to ensure their welfare.

Under the terms of the Geneva Convention, killing a lawful combatant who had surrendered was murder.

POW killings

In comparison with the atrocities meted out on the Eastern Front, Commonwealth POWs held by German forces in Europe were generally treated well, but this was not always the case.

An example of the Wehrmacht's mistreatment of captured combatants came in May 1940.

At this time, the British Army was retreating towards the coastal town of Dunkirk.

At the village of Le Paradis, 100 soldiers from the 2nd Royal Norfolk Regiment were fighting a desperate rearguard action against the forces of the 3rd SS Panzer Division “Totenkopf”.

Running out of ammunition, and with many wounded men, the Norfolks surrendered.

The SS troops marched the Norfolks a small distance to a farm. They were lined up against a barn wall and mowed down with machine-gun fire. 97 men were murdered.

Two of the Norfolks managed to survive to tell the tale, hiding under the bodies of their comrades, playing dead.

The graves of the murdered Norfolks can be visited at Le Paradis War Cemetery.

The German commander behind the massacre, Fritz Knöchlein, was tried and executed for war crimes in post-war trials.

3.5% of British POWs held by Germans died during the Second World War, either through executions or the effects of illnesses or in other incidents.

POW camps

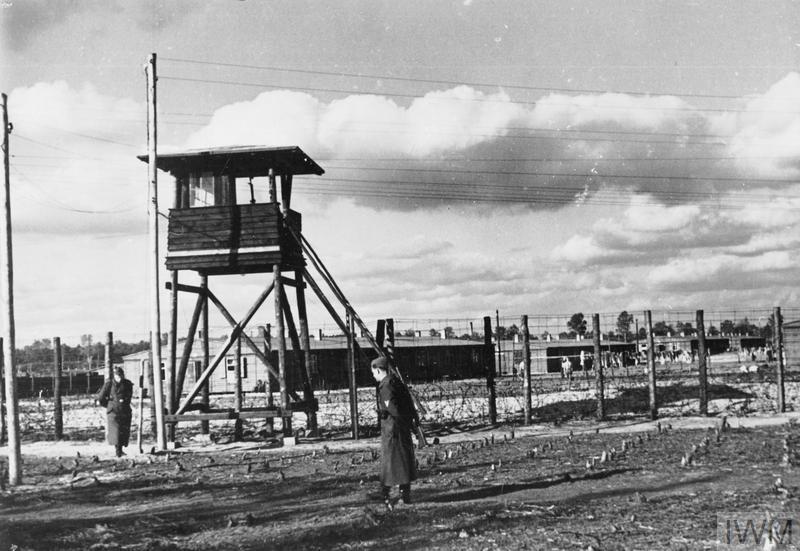

Image: Guards on duty at Stalag Luft III (© IWM)

Camps differed greatly. From the imposing mountainside castle of Colditz to sprawling temporary towns of wooden huts ringed with barbed wire, prisoner environments depended on a camp’s purpose and location.

Enlisted men and officers were separated and sent to different camps. Officers were often held in an Offizierslager or 'Oflag'. Colditz is probably the most famous example of an Oflag.

Enlisted personnel were housed in a Kriegsgefangenen-Mannschafts-Stammlager, or 'Stalag' for short. Stalag Luft III, the site of the Great Escape, was just such a camp.

As well as by rank, POWs were also divided between navy, air force, army personnel and civilians.

Life as a Prisoner of War

Image: POWs in a Stalag tending to a small garden (© IWM)

Life in the Stalags and Oflags was rarely dangerous (unless you were involved in an escape attempt of course!), but it was boring.

Prisoners of War were allowed to organise social activities and sports to keep them occupied. For their captors, bored prisoners were dangerous prisoners. POWs with little to do would spend their time plotting to escape.

So, prisoners could compete in football, rugby, and cricket matches. Equipment came from the British Red Cross, scavenged, or improvised. Some camps even had musical and theatrical societies complete with theatres and playhouses. Others, such as Stalag Luft III, had swimming pools.

POW camps were far from holiday sites though. Enlisted men were expected to work. Some could be assigned to farms and live with German families in relative comfort. Others were sent to the mines or laboured alongside concentration camp prisoners in much harsher conditions.

Officers were not expected to work but often chose to.

Escape attempts were fairly common and there was a prevailing attitude amongst the officer class that it was their duty to try and get free.

However, only a few ever successfully made the “Home Run” back to Britain or neutral territory.

Stalag Luft III

Image: Some of the raised huts of Stalag Luft III (© IWM)

Stalag Luft III was a German Prisoner of War Camp located in Sagan in modern-day Poland.

It was built in 1942. At its height, Stalag Luft III held 11,000 Commonwealth and American enlisted men and officers.

The camp was made up of multiple compounds. Each compound held fifteen single-story huts, housing 15 men who slept in bunk beds. Stalag Luft III covered a 60-acre site with an 800-strong guard force.

Stalag Luft III was one of the more comfortable prisoner camps holding Allied personnel. Each compound had its own sports field, for instance. The camp had a well-stocked library and even a Prisoner of War orchestra.

Particularly unusually, prisoners held at Stalag Luft III were allowed to bury their comrades who died in captivity with Germans providing honour guards.

Despite the comparative comfort levels, Stalag Luft III was also built to make escape as difficult as possible. It was built on especially sandy soil to discourage tunnelling and each hut was raised off the ground, making tunnelling attempts easily visible.

Because of its anti-escape measures, prisoners who already made escape attempts from other camps were sent to Stalag Luft III.

There had been previous efforts to escape tunnels from the camp before the events of the Great Escape.

In October 1943, Lieutenant Michael Codner and Flight Lieutenants Eric Williams and Oliver Philpot managed to dig a 30m tunnel under the perimeter fence and escape.

They concealed the digging from the guards with an athletics horse. The trio would dig beneath the horse and would be hidden from view while the sounds of exercising fellow inmates distracted the guards.

The three October escapees were able to evade capture and eventually made the Home Run back to the UK.

But their effort was small compared with what was to come.

Want more stories like this delivered directly to your inbox? Sign up for our newsletter for regular updates on the work of Commonwealth War Graves, blogs, event news, and more.

Sign UpThe Great Escape: Breakout

Meticulously planned for many months, the escape from Stalag Luft III was the single largest breakout from a German POW camp during the war.

The Great Escape was a much larger effort, attempting to break 200 men out of prison.

Three tunnels codenamed ‘Tom’, ‘Dick’ and ‘Harry’ were dug under the wire from within the prison huts.

Over 600 POWs worked in shifts to excavate the tunnels, while others surreptitiously disposed of the soil and collected materials to assist the work.

At the same time civilian clothes were fashioned, while official papers were forged or acquired from guards.

The Germans were aware that work was taking place. ‘Tom’ was soon discovered and destroyed, and ‘Dick’ had to be abandoned when the Germans began building on the expected exit location.

Image: A German guard in 'Harry', the famous Stalag Luft III escape tunnel (© IWM)

Work on ‘Harry’ continued, however, and after a year was completed.

The 2ft wide tunnel was nearly 30ft deep and extended more than 330ft out of the camp.

200 men were selected to take part, and on the moonless night of 24 March 1944, the escape began. Seventy-six men escaped, but the seventy-seventh man was spotted and the alarm was raised.

‘Harry’ tragically came just short of the tree line of Stalag Luft III’s surrounding woodland.

After the escape, the Germans were horrified to discover that 4,000 bed boards were missing and had been used to shore up the tunnels.

Many other items had been used, including 90 complete bunk beds, 635 mattresses, 52 twenty-man tables, 10 single tables, 34 chairs, 76 benches, 69 lamps, 246 water cans, 30 shovels, 1,000ft of electric wire, 600ft of rope, and 3424 towels.

Although they had managed to escape the camp, liberation did not last long for most of those involved. All but three of the escapees were recaptured over the following weeks and held in prisons across Poland and Germany.

Nazi Germany’s leader Adolf Hitler ordered that they should all be shot, along with the camp commandant of Stalag Luft III, the camp architect, and all the guards on duty at the time of the escape.

A number of senior Nazi officials argued against this, but ultimately fifty Great Escapers were executed to deter others from future escape attempts.

Over the next few weeks, the selected POWs were murdered individually or in small groups. Their bodies were then cremated.

Commemorating the dead of the Great Escape

The cremated remains of the Great Escapers were returned to Stalag Luft III. The newly-appointed camp commandant was appalled by the killings and allowed the prisoners to build a memorial to house the ashes.

In 1948, a Royal Air Force search team travelled to the camp to collect the ashes. They found that the memorial had been broken into, and a large number of the urns were smashed.

Image: Headstones of the Great Escapers at Poznan Old Garrison Cemetery

It’s said passing soldiers believed that gold had been hidden in the urns. The ashes of all but two of the fifty who had been executed were buried in CWGC Poznan Old Garrison Cemetery.

The Commonwealth War Graves Commission maintains graves in five cemeteries across Poland. Far from the fighting front, these men died when their aircraft were shot down or as Prisoners of War.

The cemetery was begun after the First World War when more than 170 POWs were laid to rest. It was very badly damaged during the Second World War when German and Soviet forces clashed nearby. Headstones were broken and the Cross of Sacrifice was scarred by bullet and shrapnel hits.

The cemetery was expanded after the Second World War when graves from nearby Prisoner of War camps and other temporary burial grounds in the region were brought for burial.

Today, this is the final resting place of almost 450 First and Second World War service personnel, including forty-eight of the fifty executed servicemen of the Great Escape.

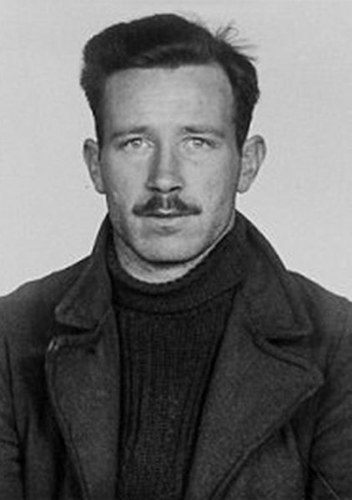

Squadron Leader Roger Joyce Bushell

“Everyone here in this room is living on borrowed time. By rights we should all be dead! The only reason that God allowed us this extra ration of life is so we can make life hell for the Hun. Three bloody deep, bloody long tunnels will be dug – Tom, Dick and Harry. One will succeed!”

RAF Squadron Leader Roger Joyce Bushell masterminded the Great Escape.

Born in South Africa, Roger was the son of a wealthy mining engineer. He was educated in Britain and studied law at Cambridge. He joined the RAF in 1932 and worked as a RAF lawyer.

In 1940 he was given command of a fighter squadron but was shot down on his first sortie over Calais during the Dunkirk evacuation.

Roger made several attempts to escape captivity. His first try was in May 1940, and he succeeded in getting to the Swiss border, only to be stopped by a border guard. His second attempt in October 1941 saw him jump from a moving train.

He made it all the way to Prague before being captured again. He arrived in Stalag Luft III in October 1942 and began planning the escape attempt that would become known as the Great Escape. His code name on the camp escape committee was Big X.

Roger was one of the seventy-six men who escaped on 24 March 1944. He was arrested the next day and murdered on 29 March 1944. He was 33 years old.

Flight Lieutenant Leslie George Bull

Born in Highbury, London, Leslie trained as an Architect at the London County Council School of Building. In 1936 he joined the RAF and flew heavy bombers in action during the first years of the Second World War.

In June 1940, he was assigned to the RAF testing and development unit at Boscombe Down, where he worked extensively on radio-counter measures and wireless intelligence, technology that would later provide a vital advantage for RAF bomber crews.

In November 1941, Leslie’s Wellington bomber aircraft suffered engine failure over occupied France and he was forced to bail out with his crew. Captured by the Germans, he was sent to Stalag Luft I. Here he met Roger Bushell, and together they worked to plot and attempt escape, and generally made a nuisance of themselves to the Germans. Leslie was particularly skilled at distilling contraband vodka from scavenged potato skins.

Leslie was transferred to Stalag Luft III with Roger in October 1942. He became a senior figure during the Great Escape, working extensively on the construction of the tunnels. On the night of the escape, he was the first of the seventy-six men out of the tunnel.

Flight Lieutenant Leslie George Bull was arrested with a small group of other POWs on a train near the Czech border. He was murdered on 29 March 1944. He was 27 years old.

Squadron Leader Ian Kingstone Pembroke Cross

Ian Cross was born in Cosham, Hampshire. He joined the RAF in 1936. Following the outbreak of the Second World War he completed a full 34-mission tour of duty and was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross.

Ian was then sent to teach new pilots at RAF Bassingbourn but soon applied to return to combat.

Ian flew a further sixteen missions before his aircraft was shot down during an attack on German shipping in the English Channel. Forced to ditch in the sea, Ian and his crew spent 24 hours in a lifeboat before being saved by German air-sea-rescue.

Ian was sent to Oflag XXI-B POW camp, where he met Roger Bushell. Together they worked on several escape attempts before being transferred to Stalag Luft III. Ian was not deterred, and amongst other attempts, he jumped aboard a German truck leaving the compound with pine trunks and branches. He did not get far before being seen.

Ian became a senior figure during the Great Escape, working extensively on the construction of the tunnels, and led the efforts to dispose of soil. Most famously he led the ‘penguin’ team, so named because they sprinkled soil out of their trouser legs as they walked.

Ian was one of the seventy-six men to escape on the night of 24 March 1944. He was recaptured very quickly. He was murdered on 31 March 1944. He was 25 years old.

Squadron Leader John Edwin Ashley Williams

John Williams was born in Wellington, New Zealand. A champion surfer, he joined the Royal New Zealand Air Force in 1938.

He first saw combat in 1942 during the North Africa Campaign, where he flew P-40 Kittyhawk fighter planes. He was an excellent pilot, and in September 1942 was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross.

In October, he was promoted to Squadron Leader and given command of No.450 Squadron of the Royal Australian Air Force.

Three days later, on 31 October, he was shot down during Operation Supercharge, the Second Battle of El Alamein.

Discovered wandering through the desert by the Germans, he was sent to Stalag Luft III, arriving in early 1944.

John was one of the seventy-six men to escape on the night of 24 March 1944, during the Great Escape.

He and four others were recaptured by a German mountain patrol while attempting to cross the Riesengebirge Mountains into Czechoslovakia.

He was murdered on 29 March 1944. He was 24 years old.

Squadron Leader James Catanach

James Catanach was born in Melbourne, Australia.

He worked as a jewellery salesman in the family business until 1940, when he joined the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF). After training in Canada, he was posted to the UK. He flew nine combat missions with the Royal Air Force before transferring to No.455 Squadron, RAAF.

In 1942, James was promoted to lead 455 Squadron, and at 20 years old, was one of the youngest squadron leaders in the history of the RAAF.

By 1942, James and his squadron were based at RAF Sumburgh on the Shetland Islands, providing cover for Artic convoys bound for Russia.

In early September, James was on route to Vaenja in Northern Russia, when his plane was shot down. He managed to crash land on the Norwegian coast. He had saved his crew from the freezing Artic sea but they were quickly captured by a German patrol.

James was sent to Stalag Luft III, where he took part in the Great Escape. He carefully learned to speak Norwegian and intended to make for Sweden with a group of other POWs. Having successfully changed trains in Berlin, James and his companions were arrested by local police near the Danish border.

On 29 March, James was driven into the countryside and murdered, shot in the back by the German secret police. He was 22 years old.

Flight Lieutenant Henry Birkland

Henry was born in Cadwell, Manitoba, Canada. He never settled before the war, working as a meat packer, a truck driver, a dishwasher, and a gold miner.

In 1940, he joined the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) and after training was sent to the UK in late spring 1941. He joined RAF Fighter Command and flew Spitfire fighter planes from RAF Turnhouse, today Edinburgh airport.

After just a month of combat patrols over Scotland and the North Sea, he transferred to No.72 Squadron on the south coast of England.

On 7 November 1941, he was flying over occupied France searching for enemy aircraft or ground targets to attack. German fighter pilot, Unteroffizier Heinz Richter of Jagdstaffel 26 found him first. Henry crash-landed near the French town of Étaples and was taken prisoner.

After interrogation, he was sent to Stalag Luft I in northern Germany. Here he planned and made several unsuccessful attempts to escape and so was transferred to the more secure Stalag Luft III.

Here he met Roger Bushell and other serial escapers who were planning what would become known as the Great Escape. Having worked as a miner before the war, he worked extensively on digging the tunnels used for the escape, regarded as ‘the toughest tunneller of them all’.

On 24 March 1944, Henry was one of 76 men to escape. He and a group of others attempted to go across country on foot but were very quickly captured by local patrols from the prison.

On 31 March he was murdered. He was 25 years old.

Lieutenant Neville McGarr

Neville was born in Johannesburg, South Africa but grew up in Durban.

At twelve years old polio left him paralyzed from the waist down. He was stubborn and worked daily to recover his mobility. Just a year later he was able to walk to Glenwood High School, where he won both academic and sporting awards.

After graduation, he worked for Lever Brothers and later for the South African Treasury Department. He loved all things fast and owned both a motorcycle and sports car.

In May 1940, Neville volunteered for the South African Air Force (SAAF). He arrived in Egypt in July 1941 and joined No.2 Squadron SAAF, flying Curtiss P-40 Tomahawk fighter planes.

In October 1941 he was on patrol with his squadron over the desert when they were intercepted by German fighters. Ambushed, the squadron suffered heavy losses in the short air battle. Neville’s Tomahawk was badly damaged, and he bailed out.

Alone in the desert, he walked for three days without food or water. On the fourth day he was saved up by passing German troops.

Neville was quickly sent to Europe and was held at Stalag Luft I in northern Germany, before being transferred to Stalag Luft III. He volunteered to take part in the Great Escape, but his physical size meant he could not work in the tunnels.

Instead, he was given command of the security detail who kept watch over the German guards. Neville was one of 76 men who escaped on the night of 24 March 1944. He did not get far, being spotted and captured by a patrol from the prison. He was murdered on 6 April. He was 26 years old.

Major Antoni Wladyslaw Kiewnarski

Born in Moscow in 1899, Antoni Kiewnarski was a remarkable individual. He served in the Polish Army during the First World War, and then transferred to the Polish Air Force in the inter war years.

He served with distinction during the German invasion of Poland in 1939, and after the surrender of Poland, he travelled to France to continue the fight.

He saw action again during the Battle of France, before finally traveling to England. He joined No. 305 Polish Bomber Squadron of the Free Polish Air Forces and flew multiple missions over enemy territory in 1941 and early 1942.

On the night of 27 August 1942, he was en route to bomb targets near the German town of Kassel when his aircraft was intercepted by a German night fighter. Three of his crew were killed during the attack, but Antoni managed to bail out of the stricken aircraft over Eindhoven in the Netherlands.

He was captured by German forces and eventually sent to Stalag Luft III. He older than many other POWs and was regarded as the elder statesman of the Polish prisoners, a father figure.

On the night of 24 March 1944, he was one of 76 men who escaped Stalag Luft III during the Great Escape. Antoni and a fellow Polish POW managed to board a train to Boerrohrsdorf but upon their arrival, they were arrested by local police. He was murdered on 30 March. He was 45 years old.

What happened to the Great Escapees not buried in Poznan?

Pilot Officer Nils Jørgen Fuglesang

Pilot Officer Nils Jørgen Fuglesang, was captured in May 1943 when his Spitfire fighter plane was shot down over Holland. Following the ‘Great Escape’ he was recaptured and murdered.

Like the others, he was cremated, and his ashes were placed in the memorial at Stalag Luft III.

In 1948 his ashes were returned to his hometown of Rasvåg in Hidra, near Flekkefjord, Norway. He was laid to rest in Hidra Cemetery and today his family cares for his grave.

Flight Lieutenant Denys Oliver Street

Flight Lieutenant Denys Oliver Street was captured in March 1943 when his Lancaster bomber aircraft was shot down.

Like Nils Fuglesang, he was murdered

following the ‘Great Escape’, and his ashes were placed in the memorial at Stalag Luft III.

When the search team removed the ashes in 1948, it was decided that Denys would be taken to Berlin.

Evidence suggests that this was because his father, Sir Arthur William Street, was a senior British official in Berlin and they thought that he would appreciate being close to his son.

Today, Denys is buried in Berlin 1939-1945 War Cemetery.

Support our work to keep their memories alive

You can help us ensure the Great Escapers are never forgotten.

As well as caring for war cemeteries and memorials worldwide, we tell the stories of those who fought and died during the World Wars. Help us keep their stories alive to make sure their sacrifices are not forgotten and their stories preserved for evermore.

Support our work and help honour the 1.7 million who never returned home

Author acknowledgements

Alec Malloy is a CWGC Digital Content Executive. He has worked at the Commonwealth War Graves Commission since February 2022. During that time, he has written extensively about the World Wars, including major battles, casualty stories, and the Commission's work commemorating 1.7 million war dead worldwide.