09 November 2022

Royal Navy Remembrance - stories from our archives

This Remembrance season, join us as we take to the seas to look at the ways navy remembrance remembers the sacrifice of Commonwealth sailors of both World Wars.

The crew of HMS Queen Elizabeth with a unique Remembrance display (LPhot Kyle Heller, UK MOD © Crown copyright 2021)

What was the Navy’s role in the World Wars?

The Royal Navy has been dubbed the Senior Service in the UK. Its history goes back over a thousand years to its founding by Alfred the Great.

For centuries, it was considered the most important of the military branches. Historically, Britain had always had a comparatively small land force stacked against a formidable fleet of ocean-going warships. The Navy was instrumental in establishing Britain as a global power.

Since its founding, the Royal Navy has acted as the UK’s guardian on the high seas, protecting our nation at home as well as our interests aboard.

During the World Wars, the Navy played an important role. It had many responsibilities, including:

- Protecting shipping lanes & convoys

- Engaging and fighting enemy ships

- Submarine warfare

- Ferrying troops and equipment to and from battlefields

- Blockading hostile ports

- Evacuating troops if necessary, such as at Dunkirk in May 1940

- Providing fire support during combined arms and joint exercises

The Royal Navy also has several fighting arms. It has its own air force, for example, in the form of the Fleet Air Arm.

Originally established under Royal Air Force command in the mid-Twenties, the Fleet Air Arm was transferred to Admiralty control in 1939. Its role is essentially to support naval operations, such as convoy defence or submarine sweeping.

Then there are the Royal Marine Commandos. These elite special forces took part in many during raids during World War Two, fighting around the world in places like Norway, the Netherlands, and the Far East.

However, in World War One, the Royal Marines were more conventional amphibious infantry. They were present at the Gallipoli Landings, for example, and played a key role in the Zeebrugge Raid in Belgium in 1918.

Men and women serving in the Royal Navy put themselves at considerable risk during war time. Casualties, although lower than the infantry, were sustained at air, land, and sea for naval personnel.

It’s estimated the Royal Navy lost 45,000 killed during World War One. The figure for the Second World War is over around 50,750 killed in action with over 800 missing.

It was not just the Royal Navy that patrolled and fought on the high seas in the World Wars. Commonwealth navies, such as the Royal Australian, Royal New Zealand, and Royal Canadian, all played important roles in both conflicts.

The importance of remembrance is such that we recognised and revere the sacrifices made by all Commonwealth navy personnel each November.

Royal Navy Remembrance Day

Image: Royal Navy crewmen at a Remembrance Day ceremony in Changi, Singapore ( LPhot Dan Rosenbaum, UK MOD © Crown copyright 2021)

Image: Royal Navy crewmen at a Remembrance Day ceremony in Changi, Singapore ( LPhot Dan Rosenbaum, UK MOD © Crown copyright 2021)

Royal Navy Remembrance Day essentially falls on Armistice Day, i.e., November 11th.

Armistice Day refers to the signing of the Armistice in November 1918. A ceasefire was agreed by Imperial Germany and the Entente Powers of France and Great Britain to come into force on the 11th hour of the 11th day of the 11th month. Fighting ended on the Western Front at this time.

Since then, Remembrance Day has been an annual tradition. On this day, a two-minute silence is held. It’s a chance for us to stop our busy lives and contemplate on the sacrifice of the men and women who fell in all wars and conflicts globally.

Remembrance Sunday takes place on the first Sunday before the 11th of November, if the 11th itself is not a Sunday. The change was made during World War Two to ensure events and services could happen smoothly during wartime.

The change of day also helped expand Remembrance Day’s meaning away from just the Armistice and World War One. Remembrance Day and Remembrance Sunday are times to commemorate and remember all victims of wars and conflict.

So, what form does Royal Navy remembrance take?

Images: Royal Navy Personnel parade past the Cenotaph on Remembrance Sunday (Sgt James Wise RAF, UK MOD © Crown copyright 2021)

Images: Royal Navy Personnel parade past the Cenotaph on Remembrance Sunday (Sgt James Wise RAF, UK MOD © Crown copyright 2021)

Like their colleagues in the other military wings, Royal Naval personnel will hold services, such as wreath laying, or be involved in local parades and processions. The latter is particularly the case if the naval personnel are stationed at one of the key naval ports of the UK.

However, the Royal Navy has a global presence. Royal Navy remembrance takes place all over the world, whether that’s on the deck of an aircraft carrier, submarine, or warship, at an overseas memorial, or even if they are on field exercises.

Senior naval staff, as well as a select number of sailors and other personnel, also take part in the annual Remembrance Sunday parade at the Cenotaph, London.

To learn more about the ways in which the CWGC takes part in national remembrance services, see our remembrance roundup.

Merchant Navy Remembrance

The Tower Hill Memorial, London, commemorates the fallen of the Merchant Navy that have no known grave.

As Remembrance Day is a day to remember all victims of war, not just those in the military, we also commemorate the men and women of the Merchant Navy on this day.

The Merchant Navy was essential in the logistical war effort. Despite being civilians, they were entrusted with huge responsibilities. Merchant fleets covered:

- Troop and equipment transport

- Moving raw materials to ports

- Import and export of essentials such as food

- Transport of munitions

- Augment the Royal Navy with additional personnel

The crews of merchant vessels not only had to contend with enemy fire both above and below the waves. They had to contend with the elements too.

The oceans and seas of the world can be dangerous places. Facing mega waves in stormy seas, or carving their way through grinding ice, or dodging tropical typhoons, men and women put their lives on the line to get their vital cargo through.

It’s hard to think of both wars having their historic outcomes without the work of the Merchant Navy.

Casualties for merchant seamen were high from the outset of the World Wars. British waters at the start of World War One, for example, were strewn with mines.

In 1917, Imperial Germany announced its policy of “unrestricted submarine warfare” making ocean crossings an even deadlier prospect.

Submarine warfare continued into World War Two with the Atlantic Ocean becoming one of the world’s key battlefields.

These conditions took a heavy toll on the Merchant Navy. More than 17,000 merchant seamen were lost in the Great War. World War Two casualties numbered over 32,000 men and women killed or missing. More than 7,000 merchant vessels were lost during both World Wars.

Merchant Navy Remembrance Day

Wreaths laid to commemorate Merchant Navy personnel on Remembrance Day.

Because of the huge importance of the merchant fleet to both World Wars, it has its own day of remembrance and commemoration.

Merchant Navy Day takes place on September 3rd. The event has been taking place since 2000 as another strand of naval remembrance.

3rd of September holds special significance for merchant seaman. It marks the day when the SS Athenia, the first British commercial ship of the war to be sunk, was hit by a German torpedo

Over 120 souls were lost when the SS Athenia went down.

Representatives of the Merchant Navy also take part in parades, services, and ceremonies up and down the country during November. They have a presence at Remembrance Sunday ceremonies in London too, marching alongside their military compatriots.

Navy stories of the fallen

We’ve selected a few stories of the fallen alongside the theme of naval remembrance.

Lieutenant Commander Malcolm David Wanklyn VC

Image: David Wanklyn alongside his Senior Engineer J.R.D Drummond, 192 (Wikimedia Commons)

Image: David Wanklyn alongside his Senior Engineer J.R.D Drummond, 192 (Wikimedia Commons)

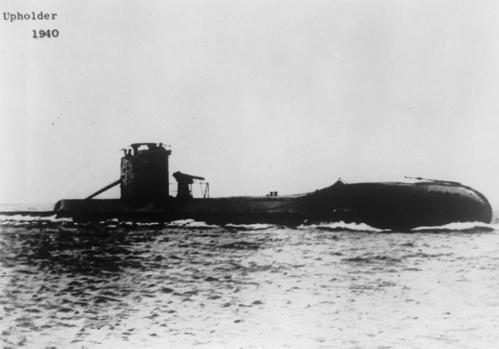

David Wanklyn is one of the Allies’ most successful submarine commanders of World War Two. At the helm of HMS Upholder, Wanklyn and his crew sank 16 enemy vessels between 1940-42.

David was born in India in 1911, the son of an engineer. He joined the Navy in 1925. His career may have ended there, as David was colourblind. This disorder should have precluded him from service, but the patient admissions officer guided the then 14-year-old David through his tests and allowed him entry.

David quickly rose through the ranks and joined the submarine service in 1932. By 1940, he had reached the rank of Lieutenant Commander and took control of HMS Upholder.

Over the next two years, David and Upholder would gain a reputation for brilliant tactical nous, incredible courage, and coolness under fire.

Upholder’s first confirmed sinking under Lt Cdr Wanklyn took place in the North Sea off the coast of Holland. From there, the submarine would spend most of its time hunting Italian and German vessels in the Mediterranean, operating out of Malta.

It was in the Mediterranean that David would earn the Victoria Cross and Upholder’s most famous victory.

Image: HMS Upholder in 1940

Image: HMS Upholder in 1940

On 23rd May 1941, Upholder spotted two tankers sporting French colours. With no neutral shipping expected in that section of the Mediterranean, David deduced the two ships were probably Italian or Vichy French.

Firing torpedoes, Upholder sank the tanker Capitaine Damiani. Its escort, the Alberta, soon began dropping depth charges. None hit and Upholder was able to slink away.

In the evening of the same day, David and his crew spotted another convoy. This time it was made of five destroyer class vessels protecting the large troop ship SS Conte Rosso.

Moving to attack, Upholder was nearly rammed by an enemy destroyer who hadn’t spotted the sub. In the midst of the convoy, Upholder fired its torpedoes and dived below the waves.

Conte Rosso was struck and the 19,000-ton ship, carrying more than 2,000 troops, began to sink. Over the next few hours, Upholder managed to dodge a furious depth charge attack from the escorting destroyers. She was never hit and made it back to Malta safely.

David’s quick thinking and bravery allowed the Allies to score quite a major naval scalp. Upholder was also operating without its ASDIC sonar system, making judgement of the distances and proximity of enemy vessels even more difficult than usual. David was essentially going in blind.

David was awarded the Victoria Cross for the sinking of the Conte Rosso. He had already been awarded the Distinguished Service Order and 2 Bars for his actions.

Submarine warfare was incredibly dangerous. Attrition rates of crews were very high. Unfortunately, Upholder and Lt Cdr Wanklyn were lost out on patrol, possibly sunk by fire from an Italian torpedo boat, on 14th April 1942.

David and his crew are commemorated on the panels of the Portsmouth Naval Memorial in Portsmouth, UK.

Upon David’s death, his Squadron Commander George Simpson said: "His record of brilliant leadership will never be equalled. He was by his very qualities of modesty, ability, determination, courage and character a giant among us."

Lieutenant-Commander William Edward Sanders VC

Image: William Edward Sanders (Wikimedia Commons)

Image: William Edward Sanders (Wikimedia Commons)

Auckland-born William Edward Sanders had been serving on pleasure and merchant craft in his native New Zealand for over two decades before the outbreak of World War One.

When war broke out in the summer of 1914, William made his way to the UK. He initially served in the Merchant Navy before being commissioned as a Sub-Lieutenant in the Royal Navy in 1916.

After rising to the rank of Lieutenant quickly after, William was given command of HMS Prize. Prize was a “Q-Ship”. These vessels were disguised as unarmed civilian vessels but were actually heavily armed with hidden guns. Their job was to hunt enemy submarines, luring them to the surface before opening fire.

Prize was patrolling waters some 180 miles of the southern coast of Ireland on 30th April 1917. It was its first time on active patrol after being upgraded to a Q-Ship. It wouldn’t be long before it and its crew’s mettle would be tested.

A U-boat, U-93, rose from the Atlantic’s cold depths and opened fire. Prize was hit several times. William’s actions would earn him a Victoria Cross.

Because Q-Ships were a close secret of the Admiralty, his original VC citation simply read: “In recognition of his conspicuous gallantry, consummate coolness, and skill in command of one of H.M. Ships in action.”

After the war, the full scope of the clash between HMS Prize and U-93 was revealed: “HMS Prize, a topsail schooner of 200 tons under the command of Lieutenant William Edward Sanders RNR, sighted an enemy submarine at three miles range and approaching slowly astern.

The 'panic party’ in charge of Skipper William Henry Brewer RNR (Trawler Section), immediately abandoned ship.

The ship’s head was put into the wind, and the gun crews concealed themselves lying face downwards on the deck. The enemy continued deliberately shelling the schooner, inflicting severe damage, and wounding a number of men. For twenty minutes she continued to approach, firing as she came, but at length, apparently satisfied that no one remained on board she drew out of the schooner’s quarter 70 yards away.

The White Ensign was hoisted immediately, the screens dropped, and all guns opened fire.

A shell struck the foremost gun of the submarine, blowing it to atoms and annihilating the crew. Another shot demolished the conning tower, and at the same time, a Lewis gun raked the survivors off the submarine’s deck. She sank four minutes after the commencement of the action in clouds of smoke, the glare of an internal fire being visible through the rents in her hull.

The captain of the submarine, a warrant officer and one man were picked up and brought on board the Prize, which was then herself sinking fast.

Captors and prisoners however succeeded in plugging the shot holes and keeping the water under pumps. The Prize set sail for land, 120 miles distant. They were finally picked up two days later by a motor launch and towed the remaining five miles into harbour.”

William was promoted the Lieutenant-Commander. For his actions in sinking another U-boat, he was awarded the Distinguished Service Order.

Tragically, William and the HMS Prize would not survive the war. The Q-Ship was sunk out on patrol by UB-48 in August 1917. William had asked to be relieved of his command, citing “overstrain” but was already out on patrol when his request was accepted.

Lt Cdr Sanders and his men are commemorated on the Plymouth Naval Memorial.

Donald Clarke

Image: Donald Clarke (Wikimedia Commons)

Image: Donald Clarke (Wikimedia Commons)

Donald Clarke was just 19 years old when he was serving in the merchant fleet aboard the motor tanker San Emiliano.

On August 8th, 1942, the San Emiliano was sailing in waters just south of Trinidad in the Atlantic. Rising from the murky depths came German U-boat U-155, launching torpedoes at the isolated motor tanker.

As soon as the torpedoes struck the San Emiliano, the ship erupted into a fireball. Inside, Donald and his comrades were engulfed in flames and very badly burnt.

Despite his horrific injuries, Donald acted quickly to save as many of his shipmates as possible. Getting them aboard a rowboat, Donald rowed as quickly as possible away from the flaming tanker.

Donald rowed for two hours, despite his burns causing his hands to stick to the oars. He eventually had to be cut free. Laying on the bottom of the small craft, Donald attempted to keep his colleagues’ spirits up by singing as they awaited rescue.

Sadly, Donald died of his injuries on August 9th. His quick actions and disregard for his own safety meant he was able to save the lives of his comrades. In fact, Donald’s lifeboat was the only one to escape the burning San Emiliano.

For his immense courage, Donald was awarded the George Cross, the UK’s highest civilian honour. He is commemorated on the walls of the Tower Hill Memorial.

Naval war memorials to visit

If you’re on a personal quest of naval remembrance or want to get involved in Remembrance Day services at a naval memorial, we look after several in the UK. Here is a couple you might be interested in visiting.

The three main naval memorials we look after the Commission are:

These were the three main “manning ports” of the UK. Sailors and crewmen were each assigned a manning port as part of the Navy’s administration processes during the Great War.

With casualties spiralling into the tens of thousands, the Royal Navy decided that each manning port should host individual memorials to the Navy’s fallen.

Because of the nature of naval warfare, it is essentially impossible to retrieve the remains of the fallen and bury them accordingly. As such, their names are inscribed on the three naval memorials.

It was decided each naval memorial would be identical in design. Their jutting central obelisks, made of Portland stone, also act as a landmark for sailors getting their bearings as they return to the UK.

Sir Robert Lorimer, one of the Commission’s original principal architects, provided each memorial’s design. Additional decorative sculpture was undertaken by Henry Poole.

The memorials were expanded after World War Two to include casualties sustained at sea or in naval-related activities during the conflict. Each addition was designed Sir Edward Maufe with the additional sculpture by Charles Wheeler and William McMillan.

We are proud of our naval memorials. They stand sentinel in these important coastal towns and ports, acting as permanent reminders of Royal Navy Remembrance.

Tower Hill Memorial

Tower Hill Memorial stands apart from the other naval memorials as it commemorates Merchant Navy personnel from both wars.

As we spoke about earlier, the men and women of the merchant fleet were the logistical backbone of both World Wars. Their contribution was enormous.

Tower Hill sits in the heart of London. At its peak, London was the British Empire’s trade hub: an economic powerhouse full of busy docks importing and exporting cargo from all over the world. It’s an appropriate location for remembrance of Merchant Navy personnel.

More than 36,000 names are commemorated on Tower Hill. It acts as a poignant reminder that ordinary civilians were caught up in the war, and many unfortunately paid with their lives.

Discover more stories of the Fallen this Remembrance Season

We commemorate 1.7 million men and women from around the Commonwealth in our cemeteries and war memorials.

Discover their stories with our Find War Dead tool.

You can also learn more about our sites around the world using our Find Memorials and Cemeteries tool.

What stories of Royal Navy remembrance will you uncover?

Have your own story to share? Tell us about a relative, loved one or someone commemorated by CWGC around the world.

There are many reasons why we remember someone. Whether its as part of a large group on anniversaries like ANZAC Day or Remembrance Sunday, or privately on birthdays and other special occasions, Remembrance happens across the world each and every day. In our blog, we often highlight a few of the stories of Remembrance and pay tribute to those we have lost.