19 May 2025

The March to VJ Day: Prisoners of the Far East

Discover moving, heartbreaking and infamous Japanese Prisoner of War stories as we explore one of the darkest chapters of the Second World War in the Far East.

Japanese Prisoners of War

Image: British troops are taken prisoner in Singapore, 15 February 1942. (AWM 1279)

Image: British troops are taken prisoner in Singapore, 15 February 1942. (AWM 1279)

As the Imperial Japanese armed forces scored victory after victory in their sweep across the Pacific and Southeast Asia in the early 1940s, they captured scores of prisoners.

More than 200,000 Commonwealth, Dutch, and American prisoners of war were taken into captivity. 85,000 Commonwealth soldiers were “put in the bag” after the fall of Singapore alone.

It wasn’t just members of the armed forces who were taken prisoner. Thousands of civilians were interned as well.

Imperial Japan had never ratified the 1929 Geneva Convention, which governed the treatment of PoWs. The Allies hoped the Japanese would still abide by the Convention’s provisions but the lack of paperwork confirming who was being held, and where, by the end of 1942 boded poorly.

Few prisoners were allowed to send any word of their whereabouts to the outside world. For many Commonwealth families at home, their loved ones had simply disappeared.

The Laha Massacre

Image: A composite photo of the Hutchins with parents Mary and Henry (AWM P05555.015)

Image: A composite photo of the Hutchins with parents Mary and Henry (AWM P05555.015)

Until June 1940, the seven sons of Mary and Henry Hutchins could be found at their home on their fruit farm near Swan Hill, Victoria, Australia, livening up the place with the joyous sounds of music, singing, and dancing.

With their two sisters, the Hutchins boys loved to sing and play. The melodic strains of their mouth organs and Henry’s accordion often brightened up evenings down at the local Old Soldiers Hall.

Sadly, those days of light and joy were darkened by the Second World War. All seven Hutchins boys enlisted in the Australian armed forces. Four would never come back to Swan Hill, dying in captivity while prisoners of the Japanese.

The eldest and middle two Hutchins enlisted in June 1940. They were followed by the youngest, Eric and Fred, who falsely bumped their respective ages up to 19 and 21 to hoodwink recruiters and serve alongside their older brothers.

Eric and Fred were joined by the remaining older brother, David, who enlisted to keep an eye on the youngest Hutchins. David was a proud father of two young children, and his wife was pregnant when he joined up.

Image: David, Eric and Fred Hutchins in their parents’ garden (AWM P05555.002)

Eric, Fred, and David were posted to the 2/21st Battalion, Australian Imperial Force. In mid-December 1941, the three Hutchins landed as part of “Gull Force” on Ambon in the Dutch East Indies (present-day Indonesia). The 2/21st was part of the force assigned to protect the important airfield at Laha.

On 29 January 1942, Ambon was invaded by a Japanese force. The defenders were quickly overwhelmed and forced to surrender on February 3.

About 300 Laha airfield defenders were summarily executed over the next two weeks. They were buried in unmarked mass graves. Eric Hutchins, the baby of the family, was among them.

The Laha Massacre was an infamous episode in Australia’s war, yet for some, the ordeal was just starting.

Into captivity

In some ways, Eric’s execution spared him a terrible ordeal. Those taken prisoner by the Imperial Japanese were subjected to horrendous treatment. Such was the fate that awaited David and Fred.

The two brothers were held in one of the worst of all Southeast Asian POW camps. Over three years, they suffered brutality, forced labour, sickness, and starvation until July 1945. Their experiences give us an insight into the appalling conditions PoWs endured at the hands of the Japanese.

On 5 July, Fred was ordered to work with severe malaria. His labour was affected by the disease; he was beaten unconscious for failing to meet his captors’ standards. Fred died the following day.

David Hutchins died of disease three weeks later. David died never knowing he had a son, born in March 1942, that his wife had died in 1944, or even that his brother Alan had died as a PoW in New Britain.

Adding to the tragedy, Japan surrendered just three weeks after David’s death.

Over two-thirds of “Gull Force” who surrendered in February 1942 were dead by VJ Day in August 1945.

Finding the bodies

Image: Mass Grave Site (No.3), Laha where the bodies of more than 60 Dutch and Australian servicemen were found (AWM 124422)

The mass graves of the Laha Massacre were discovered in December 1945 following a local tip-off.

A team of Royal Australian Engineers was sent to Ambon to recover and bring in the remains of the PoWs from the mass graves and camp cemeteries to their final resting place in Ambon War Cemetery.

A close cousin of the Hutchins boys was a member of the recovery team. It is believed he had to identify his cousins – a task he never talked about and never really recovered from.

Ambon War Cemetery

Image: Ambon War Cemetery

After the fall of Ambon in February 1942, a former Dutch army camp on the island was used to hold Australian, American and Dutch prisoners of war, captured during the invasion. The War Cemetery was constructed on the site of this camp (known as Tan Touy) after the war.

The cemetery contains Australian soldiers who died during the Japanese invasion of Ambon and Timor, plus those who died in captivity in one of the many camps constructed by the Japanese on the Moluccas Islands, including many British prisoners who were transferred from Java to the islands in April 1943.

Soon after the war, the remains of prisoners of war from Haruku and other camps on the island were removed to Ambon and in 1961, at the request of the Indonesian Government, the remains of 503 graves in Makassar War Cemetery on the island of Celebes were added to the cemetery.

The total number of graves in the cemetery is over 2,000, around 1,770 are identified burials. Of this total over half are Australians, of whom about 350 belonged to the 2/21st Australian Infantry Battalion. Most of the 800 British casualties belonged to the Royal Navy and Royal Air Force; nearly all the naval dead were originally buried at Makassar.

Death Railway

Image: Working on a Thailand railway cutting, July 1943, Murray Griffin (AWM ART25081)

War film enthusiasts will no doubt be familiar with the film The Bridge on the River Kwai. David Lean’s 1957 war epic, starring Sir Alec Guinness, depicts the struggles and defiance of POWs working on the Burma-Siam railway.

While a heavily fictionalised account, The Bridge on the River Kwai offers insights into how Commonwealth, Dutch, American, and local civilians were essentially used as slave labour by the Imperial Japanese while in captivity.

PoWs were first held where they had been captured, usually in former prisons or army barracks. Soon, however, they were sent out to crudely constructed work camps as forced labourers.

Working while sick, exhausted, and starving, they toiled away loading and unloading cargo, clearing debris from bombing raids, or working on large infrastructure projects like railways and airfields.

Among the most infamous of these forced labour projects was the aforementioned Burma-Siam Railway, known to those working on it as “Death Railway”.

Beginning in mid-1942, Japanese engineers forced thousands of prisoners of war and local forced labourers to construct a 250-mile rail line through the mountainous jungles of Thailand and Burma (present-day Myanmar).

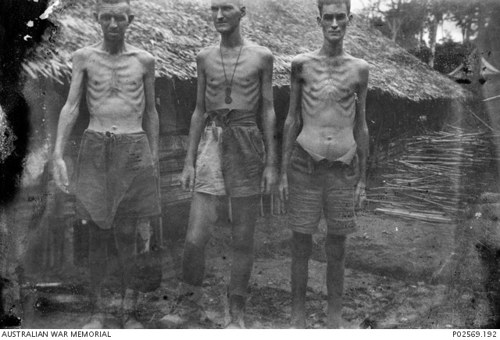

Image: Three men considered fit enough to work on Death Railway (AWM P02569.192)

Image: Three men considered fit enough to work on Death Railway (AWM P02569.192)

Hazardous terrain, an inhospitable climate, a punishing timetable, and savage overseers brutalised the Allied prisoners.

At the height of activity in mid-1943, over 60,000 Prisoners of War worked on the railway. More than 250,000 Asian labourers, known as “rōmusha”, joined the PoWs in their suffering and labour.

Inch by inch, the prisoners, using primitive tools and human endeavour, raised embankments, carved cuttings, and built bridges from forest materials. All the time, they were plagued with disease, malnutrition, fatigue, and brutal mistreatment.

They lived and worked in appalling conditions. What medical facilities existed were basic and crude. Red Cross relief parcels holding food and medicine were withheld.

Their captors created a deadly environment for the PoWs and local labourers. Around 16,000 prisoners are estimated to have died working on the Burma-Siam Railway. Rōmusha casualties may have been seven times this.

By the time the first locomotive travelled along the Burma-Siam Railway in October 1943, it is estimated a third of those who worked on its construction had perished.

Lieutenant Adrian Anthony Huxtable

Image: Lieutenant Adrian Anthony Huxtable (Sherborne School, Dorset)

Image: Lieutenant Adrian Anthony Huxtable (Sherborne School, Dorset)

The son of a rubber planter and former serviceman, Adrian Huxtable was born in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, on 10 February 1920. He had a younger brother who also served during the Second World War. Their father was a First World War veteran and a member of the Territorial Army.

He was educated in the UK, attending Sherborne School in Dorset. At Sherborne, Adrian was a house prefect. He also joined the Officer Training Corps, reaching the rank of Lance Corporal.

Contemporaries noted Adrian had a keen sense of humour and a real zest for life. After school, he joined the territorial Royal Artillery, serving with the 88th Field Regiment.

On the outbreak of the Second World War in September 1939, the Huxtables heeded the call. Adrian’s father donned his uniform once more while Adrian’s younger brother enlisted with the Royal Navy.

Adrian was sent to France with his regiment and was evacuated at Dunkirk in May 1940.

In late 1941, Adrian was posted to Singapore, joining the 9th Indian Division and Kuala Lumpur. The Japanese invaded four weeks later. Subsequently, Adrian fought in the Malaya campaign in present-day Malaysia, and the defence and the Fall of Singapore, where he was taken into captivity.

Following the defeat in Singapore, Adrian was taken into captivity. He was one of the 60,000 Allied and Dutch soldiers put to work on the Burma-Siam railway. Sadly, Adrian contracted dysentery and died on 5 July 1943, aged 23.

Adrian’s obituary, published in the 8 September 1945 edition of The Times, reads:

“Adrian’s life was gloriously clean, unselfish, and honest. He loved life and the simple things, and the way of peace, and to endure great hardships after the fall of Singapore. Those who knew him… will never forget his happy, charming personality and his dauntless courage to the end.”

In Dorset, his family set up a market next to the spot where his parents would be buried “In happy memory” of Adrian. Adrian, however, lies half the world away alongside his comrades in the Commonwealth War Grave Commission’s Kanchanaburi War Cemetery.

Kanchanaburi War Cemetery

Image: Visitors contemplate the bronze plaque grave markers at Kanchanaburi War Cemetery

Those who perished during the construction of the Burma-Siam Railway were originally buried in makeshift isolated graves close to where they fell or camp burial grounds.

After the war, recovery teams had a tough job repatriating these war graves, bringing them into the newly built war cemeteries in Thailand and Myanmar.

Kanchanaburi War Cemetery is one of three major CWGC sites in Thailand. It is only a short distance from the site of the former Kanburi prison camp, where many prisoners passed through on their way to work camps along the railway.

Those buried at Kanchanaburi are POWs who died working on the southern Bangkok to Nieke section of the Burma-Siam railway.

Over 5,000 Commonwealth casualties are buried at Kanchanaburi, alongside nearly 1,900 Dutch victims of the Railway of Death.

The nearby Chungkai War Cemetery and Thanbyuzayat in Myanmar also commemorate victims of the Death Railway, holding 1,400 and 3,100 war graves, respectively.

Want more stories like this delivered directly to your inbox? Sign up for our newsletter for regular updates on the work of Commonwealth War Graves, blogs, event news, and more.

Sign UpHell Ships

Prisoners of War were sent to work all over Southeast Asia and the Japanese home islands. Those transported by sea were packed into holds of cargo ships more accustomed to carrying freight than humans.

Under the baking tropical sun, hundreds of men were crammed into cargo holds with little room to sit or lie down. Ventilation was often heavily limited.

Lucky small PoW groups might take turns on deck but, more often than not, prisoners were kept in the hold for entire voyages, some of which could take weeks.

Food, water, sanitation, and medical care were essentially non-existent. Wounds festered, the sick got sicker, and death from asphyxiation was a very real risk in the cramped confines of a hell ship.

If the conditions weren’t hard enough to endure, hell ships carried no identifying PoW or hospital markers, making them fair game for Allied submarines prowling the Pacific. The great tragedy is that thousands of Allied prisoners of war were inadvertently killed by their own side in attacks on hell ships.

The first hell ship to be sunk by Allied subs was the Montevideo Maru, torpedoed by a US submarine on 1 July 1942.

The exact casualty figures were never published by the Japanese authorities, but it’s believed that 850 Australian prisoners of war perished alongside 200 civilian internees in the attack. Most were still locked inside the hold as the ship sank.

Flight Lieutenant Grahame Prebble “Tiny” White

Image: Flight Lieutenant Grahame Prebble White

Image: Flight Lieutenant Grahame Prebble White

24-year-old Grahame White, known as “Tiny” to his squadron mates, was the only New Zealander among the 540 British and Dutch prisoners of war aboard the Suez Maru when it left Ambon for Java.

Before the war, Grahame worked as a commercial artist in Wellington. He enlisted in the Royal New Zealand Air Force and saw service in the skies over Malaysia, Singapore, and Java. He was captured in Java in March 1942.

Ironically, the captive pilot was one of a group of prisoners sent to build an airfield on Ambon, the site of the notorious massacre at Laha, in March 1942.

By November, Grahame and his comrades were too sick to continue working. They were packed aboard the Suez Maru for transportation back to Java. With them were 200 sick and wounded Japanese soldiers.

As it made its way between the Indonesian islands, the cargo-come-transporter fell into the crosshairs of a US submarine and was torpedoed.

Around half of the prisoners were trapped below deck and drowned. The rest managed to escape into the ocean. Four hours later, a Japanese navy ship arrived and picked up the surviving Japanese. Soldiers with rifles and machine guns opened fire on the stricken prisoners of war bobbing in the water. None survived.

As Grahame and his comrades have no known grave but the sea, they are commemorated on the Commonwealth War Graves Commission Singapore Memorial.

Sandakan Death Marches

Image: A simple wooden cross, nearly lost to the undergrowth, marks the grave of a victim of the Sandakan Death Marches (AWM 042578)

Image: A simple wooden cross, nearly lost to the undergrowth, marks the grave of a victim of the Sandakan Death Marches (AWM 042578)

After the loss of Singapore, several thousand British and Australian PoWs were sent to camps in the Sandakan area of North Borneo’s eastern coast. They had been ordered to build an air strip for Japanese war planes.

As ever, the men were kept in appalling conditions, where the overworked prisoners were subjected to starvation and savage beatings.

By February 1945, the tide of the war had decisively turned in the Pacific and Asian theatres.

Japanese commanders anticipating an invasion of North Borneo decided to move their captive charges some 160 miles inland to Ranau.

So began the Sandakan Death Marches.

Already exhausted, malnourished and suffering from illness, the prisoners were forced to march into dense jungle. Prisoners who fell on the journey were killed. Those who survived this latest ordeal were immediately put to work on starvation rations.

Out of the 2,000 men who left Sandakan, only 260 arrived at Ranau. Come July 1945, the majority had died.

Only six escaped, avoiding recapture and execution with the help of locals who hid them until liberating troops arrived.

Captain John Bernard Oakeshott

Image: Captain John Bernard Oakeshott (Australian War Memorial)

Image: Captain John Bernard Oakeshott (Australian War Memorial)

In 1939, John Oakeshott was a 38-year-old married father of two, working as a doctor in Lismore, North South Wales, Australia.

Come wartime, John chose to use his medical training by joining the 10th Australian General Hospital, shipping out to Singapore in 1941. Like tens of thousands of Commonwealth troops, he was captured when the city fell, becoming a prisoner of war.

John was sent to Borneo in 1942 and was transferred to Sandakan in June 1943.

In 1945, John was part of the second group forced on the Sandakan Death Marches. He was one of the last 38 PoWs left alive at Ranau by the end of July.

A guard warned one of John’s fellow prisoners that the Japanese intended to kill them. John was offered the chance to join the small band of POWs planning their escape but chose to remain with the sick and dying men. He did, however, give one of the escapees his boots.

John and 14 others were shot by their Japanese guards on 27 August 1945. Tragically, the Japanese government had surrendered 12 days earlier.

Back in Lismore, John’s family had heard nothing of him since a brief Red Cross postcard in late 1942.

Two months after celebrating VJ Day, hoping for John’s return, his wife received a grim telegram informing her of her husband’s death. Receiving such news must have been devastating.

Today, John is buried in the Commonwealth War Graves Commission site at Labuan War Cemetery in a grave with four of the men he refused to leave.

Labuan War Cemetery

Labuan War Cemetery is the final resting place of more than 3,900 Commonwealth servicemen of the Second World War. 2,700 were brought here after the cemetery at Sandakan could not be made permanent.

When the Australian Army Graves Service entered Borneo they followed the route from Sandakan to Ranau, and found many unidentifiable victims of this infamous march. These and other casualties from Battlefield Burial Grounds and from scattered graves throughout Borneo were taken in the first instance to Sandakan, where a large number of prisoners of war were already buried.

This flat coastal area, however, was subject to severe flooding and it proved impracticable to construct and maintain a permanent cemetery. The Sandakan graves, numbering 2,700 of which more than half were unnamed, were therefore transferred to Labuan War Cemetery in 1949, which was specially constructed to receive graves from all over Borneo.

As well as the graves from Sandakan, about 500 are from Kuching where there was another large prisoner-of-war camp. The total number of burials is 3,922. The preponderance of unidentified graves is due to the destruction of all the records of the camps by Lieutenant-Colonel Suga, the Japanese commandant, before the Australians reached Kuching, his headquarters. When apprehended, this man committed suicide rather than face questioning on his conduct of the Borneo Camps.

Fitting Resting Places for Far East Prisoners of War

Image: A trio of visitors to Chungkai War Cemetery, one of the stunning sites so beautifully maintained by local CWGC teams

The truth of what the Japanese prisoners of war endured only came out following the Japanese surrender in 1945.

Dribs and drabs of information had been released as early as 1943, and more continued as the war went on, but the full extent of the malnourishment, disease, and brutal treatment meted out to the prisoners only became clear when camps were found and liberated.

Secret records and diaries kept by Prisoners of War were retrieved. Japanese guards and overseers were themselves captured and interrogated. Some, like the Japanese commander in Borneo, committed suicide rather than face the consequences of their actions.

Up and down the infamous Death Railway, along jungle tracks, and within POW camp cemeteries, the final resting places of those who died in captivity were sought.

The CWGC strives to make our beautiful cemeteries and memorials in Southeast Asia a fitting tribute to tens of thousands of servicemen and women who died as prisoners of war.

Today, these sites are carefully maintained by dedicated local crews and maintenance teams, ensuring they remain appropriate places for the commemoration of so many who suffered so much at the hands of their captors.