31 May 2024

The Untold Stories of D-Day Veterans

Discover D-Day veteran stories from those who were there as well as those who sadly lost their lives in this momentous Second World War battle.

Fascinating D-Day Stories from Veterans

The events of June 6, 1944, have achieved near-mythical status but it's important to remember D-Day was a very real battle fought by very real people.

We are now some eight decades removed from D-Day. Sadly, the number of veterans who were there is getting smaller every year.

Their testimonies provide us with a living link to the Normandy Invasion and a tangible connection to the past.

In 2019, on the 75th anniversary of D-Day, Commonwealth War Graves was lucky enough to speak with several D-Day veterans and record their stories.

Here is a small selection of Normandy landing stories from those who were there – and some who lost their lives in the fight for Europe’s liberation - so we may always remember their experiences and sacrifice.

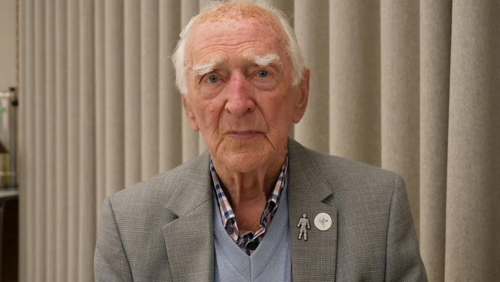

D-Day Veteran Hector Duff

Image: Hector Duff in 2019, around the time of D-Day's 75th anniversary

Image: Hector Duff in 2019, around the time of D-Day's 75th anniversary

Hector Duff served with the 7th Armoured Division, also known as the Desert Rats. Their early war was fought in the deserts of North Africa and Italy, but by June 1944, 7th Armoured was destined for Normandy.

Hector had originally been a tank driver but for D-Day he had been reassigned to an armoured car, a much smaller, lighter vehicle used for scouting and reconnaissance.

“The Day came when we were going to go,” Hector said. “And we went to Felixstowe, and they drove the armoured car onto a small landing craft.”

“I will never forget the first look I saw, the boats were going from France, and I stood up on top of my armoured car and could see the 5,000 boats.”

The Royal Navy on D-Day led a flotilla of more than 7,000 vessels of all shapes and sizes. The invasion fleet was one of the largest ever assembled, including hundreds of landing craft.

“We landed, I didn't land until one o'clock between twelve and one,” Hector said. “The infantry, our infantry, had been there in the morning since about five, six o'clock. They had eliminated all the short, small arms fire, that’s the rifles and machine guns and that sort of thing, and all the anti-tank guns, they'd wiped them all out, so we were in a sort of free run into the beach

“Unfortunately had to go through all the men that had been knocked up, killed.

“They said we were floating about in the sea that was red with blood. It wasn't as bad as that really. It was bloody red in places. I think there were 10,000 on the first day that never landed on the shore.

“But these men, the wounded, they were being looked after by men dashing between shell bursts and that sort of thing.

“They tried to get them ashore, drag them ashore, and put them in body bags as we were told. And that was it. And then we sailed in between them as best as we could and landed.

“But two or three days after we were fighting, we were fighting around a place called Tilly-sur-Seulles”

“And we took that village. and the Germans retook it. And that was retaken, taken, captured again, I think about forty times in two or three days. And I found out it was all in a little place, an area which is called Jerusalem.

“Now there's one little grave, little cemetery there. I think it's 49 or 39 people in it. And one of them was John Banks. A little lad, you know that as well. He, John Banks, was 15 or 16, yeah. And he was killed, I think, on a Tynwald Day, that's July the 5th, in the Isle of Man where I’m from.

“And we always go back there to see that John Banks, Tony, and his major. other time we all go together and see that it was wonderful.

“I'm very, very more than pleased with the work that the Commonwealth War Graves do. Yes, they're wonderful. I can't say how pleased I am to say how good you look after the cemeteries.

“I think we have an obligation to see that we do look after them. And that little poem that John, the Canadian man, wrote in Flanders Fields. And he says, if you break faith in us who die, we shall not sleep.”

D-Day Veteran Ken Hay MBE

Image: Ken Hay MBE

Image: Ken Hay MBE

Ken Hay MBE, 98, is one of the last remaining Veterans of D-Day and the Battle of Normandy.

Ken served with the Essex and Dorset Regiments. He relayed his Normandy experiences to CWGC five years ago.

“When we heard about D-Day, we'd seen the planes going over, we knew something was up,” Ken said. “Eventually they put us on lorries and took us down to Southampton. And my brother and I had a sort of last cigarette and said goodbye to England.

“And we went over and of course, you saw the actual carnage there, still bodies floating in the water and so on.”

For many D-Day veterans like Ken, Operation Overlord was the first time they had been involved in fighting. Ken was just 17 at the time of Battle of Normandy. Such carnage must have been eye-opening.

After pushing inland passed Longues-sur-Mer, and the Atlantic Wall casemates, Ken and his unit found themselves in the Normandy countryside. With a network of fields, sunken roads, twisting country lanes and thick hedgerows, fighting in Normandy itself was just as difficult as storming the beaches.

Ken was taken captive in Normandy while on patrol and spent the rest of the war as a POW in Poland. Here, Ken shares how he came to be “in the bag” and taken prisoner.

“And then came disaster as far as I was concerned, as far as the patrol was concerned. And we went out, and I was out on the left-hand side coming in, as it was happening, the guy coming in at the side was my brother, leading his section, he was the section leader, coming in.

‘That you, Bill?’

‘Yeah. That you, Ken?’

‘Yeah.’

“So, I said, ‘I'm scared’. And he said he'd been my hero, you know, commando. He fought in Norway at the beginning of the war as well. And he was my hero and I said, I'm scared. And he said, ‘What do you think I am?’ And I didn't imagine that he could be scared, you know.

“So, we went through, and we were crawling across the field. Scouts went forward and came back. And it so happened, that I was lying near the officer in the middle of it with just a bit of a heap.

“We weren't in a long line or anything like that, just moving across. The scouts came back and reported that Jerries were walking around with tea buckets. Well, I presume it'd be coffee, but they were walking around with buckets.

Explore our sound archive marking of the end of the Second World War, featuring real-life testimonies from veterans.

Explore the archive“So, the officer, instead of sending for the platoon sergeant, who was the next senior team, sent West Corporal Hay and sent for Bill, because Bill was the only one, I think, in our platoon with any experience of war.

“Bill came up, laying there, and I heard the whole conversation.

“’What do you want?’ And the officer reported what the scouts had seen, they've reported. So Bill said, I'm not surprised. So, he said, ‘what do you suggest we do? So, my brother said, ‘Go back. Abort the mission, back.

“So, the officer said, ‘Right, let's turn round and go back’.

“Bill said ‘It’s not as easy as that’

“'Why'd you say that?’ the officer said

“ 'Well, I think that head road we came through is manned,’ said Bill ‘They've let us through. Don't think they're gonna let us through back.

“And then we had a battle on our hands and there was tracer coming out and grenades coming out and it was all very close, you know, it wasn't at distance. And we had a battle for some while and then it all died down and then somebody would move, and firing started again.

“This was up against the 12th SS HitlerJugend people. And they were watching us, I'm sure.

“And then they stepped out with tommy guns: ‘Hande hoch! For you, the war is finished!’ They didn't say that then, but that was it.

“We were a group of 30, went out. and my mother told me a year later when I got home that 16 got through, got back.

“And that was the end of my not-very glorious war as an infantryman.”

Lieutenant Den Brotheridge – D-Day casualty

Lieutenant Den Brotheridge was one of nearly 2,000 Commonwealth D-Day servicemen who would never make it home from Normandy.

In fact, Den has the unique distinction of being the first Allied servicemen to be killed by enemy fire on June 6, 1944.

Herbert Denham (Den) Brotheridge was born on 8 December 1915, the son of Herbert Charles and Lilian Brotheridge, of Smethwick, Staffordshire.

Educated at Smethwick Technical College, he was a keen sportsman playing football for Aston Villa Colts and cricket for Mitchell and Butlers, Smethwick. He later became a weights and measures inspector for Aylesbury Borough Council and married Margaret Plant on 30 August 1940.

Den was commissioned into the Ox and Bucks Light Infantry in July 1942 and quickly became a popular member of his unit.

At 00.16 hrs on 6th June, his glider landed less than 50 feet from the bridge over the Caen Canal but sadly was hit by machine gun fire while leading his platoon in the first charge.

He was taken to the Casualty Collection Post but died moments later. He is believed to have been the first Allied serviceman to die through enemy action on French soil during the Normandy Campaign. Den was 29 years old.

His wife Maggie gave birth to their daughter Margaret two weeks later.

Den is buried in Ranville War Cemetery where some of the earliest D-Day war graves can be found.

Flight Lieutenant Francois August Venesoen - D-Day casualty

The Invasion of Normandy was not just a naval and infantry fight. Fighter pilots were involved too, alongside aircraftmen of all ranks, to clear the skies of enemy warplanes before, during, and after the Normandy Landings.

Amongst their number was Belgian Francois August Venesoen.

Francois was born 19th of October 1920 in Antwerp.

Sometime in the 1930s he enlisted into the Belgian Air Force and underwent pilot training.

With the fall of his country and then France, he came to the UK on the 23rd of June 1940 on the. He was then posted as an Air Gunner with 235 Squadron at Bircham Newton, and then 272 Squadron at Aldergrove, both units flying the Blenheim.

Francois still wanted to be a fighter pilot and was accepted for pilot training which he had completed by the 18th of December, 1941 when he was posted to 350 (Belgian) Squadron equipped with the Spitfire.

The squadron flew escorts, sweeps, and patrols but its first major action was the Dieppe Raid.

In this, Venesoen claimed two FW190s shot down and on his fourth sortie of the day had part of his wing tip shot away but returned to base. Then, in November, he shot down a JU52 transport over France and then posted to 610 Squadron.

On the 29th of March, 1943 at 11.15 Fw190A-5 2576, Black 4, 10/JG54 shot down by a Spitfire Vb of 610 Squadron in the sea 500 yards off Brighton beach Uffz Joachim Koch was killed and buried Brighton (Bear Road) Cemetery where he still rests.

JG54 was engaged in a schwarm attack on Brighton. At this time F/O Francois Venesoen (Belg), and Sgt Edward Sutton of 610 Squadron were engaged in cine gun practice in the area.

Flying in thick cloud, the pair descended to break through the cloud at lower level, and as they did so they saw four aircraft over Brighton and explosions in the town.

He informed control that there were “rats” about. He caught up with the third enemy fighter and attacked from between 600 and 200 yards and saw the hood fly off and black smoke come from the engine before it turned on its back and dive into the sea. Following the combat, he damaged two FW190s flying on Circus 290 in April 1943.

Francois’ last claim came on the 24th of September when he shared a Me110 near Caen. In December he was gazetted with the DFC.

On 6 June, 1944, Francois took off at 04.34 for a patrol over the Normandy beachhead in Spitfire MkV EN950 MN-H.

The squadron records that:

“Over the Channel F/Lt Venesoen had to bale out owing to an internal glycol leak. His parachute opened alright and he was last seen by his Number 2 (F/O L Siroux) alighting on the rough sea and struggling in the water, trying to inflate his dinghy. After F/O Siroux had pulled up to lead 3 launches to the spot, no trace of F/Lt Venesoen could be found”.

Francois has no known grave and is remembered on the Runnymede Memorial.

Thanks to Philip Baldock for sharing Francois’ story.

Introducing For Evermore: Stories of the Fallen - the exciting new way to read and share stories of the Commonwealth's war dead. Got a story to share? Upload it and preserve their memory for generations to come.

Share and read storiesHow many D-Day Veterans are still alive?

Sadly, the veterans of D-Day are passing away. Their numbers dwindle every year.

The veterans of D-Day were, and in some cases still are, regular visitors to Commonwealth War Graves’ D-Day memorials and cemeteries.

It’s here their comrades are commemorated in perpetuity. It is always a great honour to see those who took part in the fight to liberate Europe at CWGC cemeteries and memorials.

Famous D-Day veterans

Stan Hollis VC

Image: Statue of Stan in his native Middlesbrough (Wikimedia commons)

Image: Statue of Stan in his native Middlesbrough (Wikimedia commons)

Did you know only one Victoria Cross was awarded to Commonwealth forces on D-Day?

Veteran Stan Hoillis, Company Sergeant Major, D Company, 6th Battalion Green Howards, was awarded Britain’s highest military honour for valour, for his actions on D-Day.

Stan was 31 at the time of Operation Overlord. He had already seen action in North Africa and Sicily. Because of his age and experience, younger members of Stan’s unit used to look up to him.

At Normandy, Stan was commanding three machine gun and three mortar teams to cover D Company’s advance up Gold Beach.

D Company had been charged with capturing a house with a distinctive round driveway as part of their early assault objectives. As the company advanced, it came under heavy fire from a machine gun hidden in a concealed pillbox in the house’s garden.

Stan charged 30 yards over open ground, under fire, and stuck his Sten gun into the pillbox slit and emptied his magazine. He then climbed on top of the emplacement and threw a grenade inside. Entering the pillbox, Stan took the surviving Wehrmacht soldiers prisoner.

Noticing a slit trench leading into the garden, Stan advanced down it alone and found himself facing another pillbox. Capturing this second fortification,

Stan had taken 30 POWs single-handedly.

At approximately 11.00 am, Stan was now acting commander of 16 platoon, its officer having been killed.

Stan spied a German field gun in a hedge and aimed to destroy it. Grabbing a PIAT, a man-portable anti-tank weapon, Stan and two Bren gunners crawled through a large rhubarb patch and closed on the German gun.

Stan missed with his first shot. The German field gun turned and fired at the three British soldiers but miraculously missed.

Stan ordered the retreat but his comrades either couldn’t hear him or were pinned in place by nerves. Taking responsibility for their safety, Stan leapt up with a Bren gun, firing from the hip in the open ground.

Despite being just 100 yards away, the German gunners missed Stan and his two fellow soldiers had time to escape.

For these two actions, Stan was awarded the Victoria Cross.

Stan survived the war and worked as an engineer, pub landlord, and sandblaster before he passed away on 8 February 1972.

David Niven

Image: Lieutenant-Colonel David Niven smiles for the camera in a commandeered Citroen car with a Royal Engineers officer, during his service with Phantom GHQ Liaison Regiment in France (© Ernie Johnson (HU 99822))

Image: Lieutenant-Colonel David Niven smiles for the camera in a commandeered Citroen car with a Royal Engineers officer, during his service with Phantom GHQ Liaison Regiment in France (© Ernie Johnson (HU 99822))

Actor David Niven became synonymous with “officer and a gentleman” sophistication during his career, holding an upright bearing with a laconic sense of humour and gentle personal charm.

What people may not know is that David Niven actually was an officer in the British Army before and during his time as a film star.

In 1928, a young David enrolled in Royal Military College Sandhurst, beginning a five-year military career.

He served with the Highland Light Infantry in Malta, where one of his commanders was future Battle of Arnhem figure Major Roy Urquhart.

The peacetime military bored David who, after being promoted to Lieutenant in 1933, saw no further path for advancement. He resigned his commission by telegram after heading for the United States.

As Hollywood came calling, David began a career as a leading man but on the outbreak of the Second World War in 1939, he returned to the UK and reenlisted.

David was recommissioned as a Lieutenant in the Rifle Brigade (Prince Consort’s Own) in February 1940 and transferred to a motor training battalion.

Craving more excitement, David volunteered for the Commandos. Following their tough, unrelenting training, David was promoted to war-substantive captain and given command of A Squadron GHQ Liaison Regiment, aka “Phantom”.

In the Normandy battle, David and Phantom were tasked with locating and reporting enemy positions and updating rear commanders on changes in the main battle lines.

David ended the war with the rank of Lieutenant-Colonel. He did not speak much about his wartime experiences post-war, after a profoundly moving moment at the grave of a son of some of David's American friends in Bastogne, Belgium.

David recalled finding the grave and its effect on him years later: “I found it where they told me I would, but it was among 27,000 others, and I told myself that here, Niven, were 27,000 reasons why you should keep your mouth shut after the war”.

Richard Todd

Image: Richard Todd right, with Lieutenant Tony Bowler, in Wales ahead of D-Day (Wikimedia Commons)

Image: Richard Todd right, with Lieutenant Tony Bowler, in Wales ahead of D-Day (Wikimedia Commons)

The Longest Day is regarded as one of Hollywood’s best portrayals of the Normandy landings.

The filmmakers collaborated with several Axis and Allied participants of D-Day. Authenticity was paramount. Amongst those consulted were John Howard, commander of the airborne assault on Pegasus Bridge, and Lord Lovat who commanded 1st Special Service Brigade.

D-Day veterans were even in the cast, most noticeably Richard Todd.

Richard was the son of Irish doctor and former British Army officer Andrew William Palethorpe Todd.

Upon leaving school, Richard actually began training for a military career at Royal Military Academy Sandhurst before swapping the parade ground for the stage.

Richard’s acting career was put on hold in 1939 when he re-entered Sandhurst after enlisting in 1939.

After completing officer training in October 1942, Richard was commissioned into the King’s Own Yorkshire Light Infantry. After a period as liaison officer to the 42nd Armoured Division, Richard requested a transfer to the Parachute Regiment as he thought it would give him a better chance of seeing action.

Richard certainly saw action. With the 7th (Light Infantry) Parachute Battalion, Richard dropped into Normandy in the early hours of D-Day as part of the airborne assault.

The 7th Parachute Battalion went into action shortly after glider-borne troops had landed and captured the bridges over the Orne River and Caen Canal.

At the battle of Pegasus Bridge, Richard met Major John Howard there and helped repulse the fierce German counterattacks that occurred throughout the day.

Five days after D-Day, Richard was still at Pegasus Bridge and by this time had been promoted to Captain.

Following the war, Richard went on to become one of his generation’s most respected actors. In The Longest Day, Richard portrayed his old commanding officer Major Howard. Richard also used his own airborne beret that he’d worn in Normandy during the film.

Celebrating and commemorating D-Day veterans

Returning to Normandy for D-Day anniversary

On the 80th Anniversary of D-Day, the remaining veterans will be returning to Normandy to mark the 80th anniversary of the Normandy Campaign.

Commonwealth War Graves Commission will be hosting several events in Normandy which will see interaction between veterans of the battle interacting with younger generations.

The Great Visual will light every war grave in Normandy to highlight the enormous sacrifice made by those who killed during the liberation of France and Europe.

Visit Legacy of Liberation today for a full list of our D-Day anniversary events.

Where are D-Day veterans laid to rest?

The Commonwealth War Graves Commission cemeteries and memorials in Normandy hold many D-Day war graves.

CWGC’s mission is to commemorate the war dead for the First and Second World Wars in perpetuity, including the fallen of the Battle of Normandy.

There are over 20 constructed sites and D-Day memorials and many hundreds more individual graves and scattered burials throughout the former Normandy battlefields.

Some of the key Commonwealth War Graves sites including D-Day burials and fallen veterans include:

Ranville War Cemetery

As touched on earlier, Pegasus Bridge was one of the key battles of the Normandy Invasion’s early stages.

The village of Ranville, close to Pegasus Bridge, was one of the first villages to be captured by the Allies on D-Day. It now holds one of the largest CWGC war cemeteries in Normandy, holding 2,500 war graves.

Hermanville War Cemetery

Hermanville War Cemetery lies less than a mile from Sword Beach.

Just over 1,000 war graves can be found at Hermanville. Nearly all of the soldiers buried here were killed in the early days of June 1944.

Bayeux War Cemetery

Bayeux was spared from most of the fighting in Normandy, but it was one of the earliest towns to be liberated.

Bayeux War Cemetery is the largest CWGC cemetery in Normandy, holding over 4,100 Second World War graves.

The Bayeux Memorial commemorates by name a further 1,800 Normandy casualties who have no known war grave.

Beny-sur-Mer Canadian War Cemetery

Some 2,000 Canadian servicemen are buried at Beny-sur-Mer Canadian War Cemetery. It lies some two miles inland from the Normandy beaches, near the village of Reivers.

Most of the men buried here were killed during the assault on Juno Beach, or in the advance on Caen. Caen was an important transport hub and the site of much bitter fighting in the summer of 1944.

Ryes War Cemetery

Located a little way inland from Gold Beach, Ryes War Cemetery lies in the village of Bezanville.

The first burials came in the days after D-Day when casualties were moved off the beach at Arromanches.

Over 650 Commonwealth burials sit within Ryes War Cemetery. The site also holds 300 or so German war graves, cared for by CWGC.

La Delivrande War Cemetery

Lying just over a mile inland from Sword Beach sits La Deliverande War Cemetery

Those buried within died across the length of the Normandy Campaign, either on Sword Beach on D-Day morning, or in the thrust to Caen.

Overwhelming British, the cemetery also contains several German, Australian, Canadian, and Polish war graves.

Download the For Evermore app and take your own Normandy journey

We are very excited to introduce our new For Evermore mobile app available on iOS and Android!

Bridging the gap between virtual and digital commemoration, this new app puts some of our most iconic cemeteries and memorials in the palm of your hand.

Explore our sites virtually with virtual tours powered by Memory Anchor, curated by expert CWGC historians. From the Western Front to the Pacific Theatre, explore historic sites at your leisure.

The app draws in thousands of stories from For Evermore: Stories of the Fallen, our online digital archive. Now you can visit a site and scan a headstone to see if we’ve got a story about them.

Download the app today and begin your own For Evermore journey.

Your support keeps these stories alive - donate to Commonwealth War Graves Foundation

Author acknowledgements

Alec Malloy is a CWGC Digital Content Executive. He has worked at the Commonwealth War Graves Commission since February 2022. During that time, he has written extensively about the World Wars, including major battles, casualty stories, and the Commission's work commemorating 1.7 million war dead worldwide.

Want more stories like this delivered directly to your inbox? Sign up for our newsletter for regular updates on the work of Commonwealth War Graves, blogs, event news, and more.

Sign Up