07 January 2022

Why do we commemorate war? The importance of remembrance

War is everywhere in modern culture. It is the backdrop to video game franchises and Hollywood blockbusters and the impact of war remains a part of the news cycle.

But why do we commemorate war? Why do we choose to remind ourselves so regularly and so publicly of its costs?

It’s something the Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC) does every day of the year through our care of memorials and cemeteries around the world.

What does it mean to commemorate something?

Commemoration isn’t just limited to one or two days a year, it can be attending a national memorial service on Remembrance Sunday or visiting a local cemetery to pause by a headstone and pay your respects to the fallen.

To commemorate means to show respect for someone or something. This could include laying a wreath at a ceremony, talking to family about the two world wars or taking a moment out of our busy lives to pause and reflect on the sacrifice given by past generations.

Why do we have commemorations?

For us, there are more than 1.7 million reasons to commemorate war – or more accurately, the men and women who lost their lives rather than the engagements, battles, and conflict as a whole. It is a task that begins with every single person who chose to put their life on the line for the Commonwealth and paid the ultimate sacrifice.

It is a reminder that away from the screen there is no reset button, and that the costs were real.

How are wars remembered and commemorated?

Our work to commemorate the fallen from across the Commonwealth from the two World Wars takes many forms. On national days of remembrance like Armistice Day or Anzac Day you may visit or see on TV one of our vast cemeteries where many thousands are commemorated.

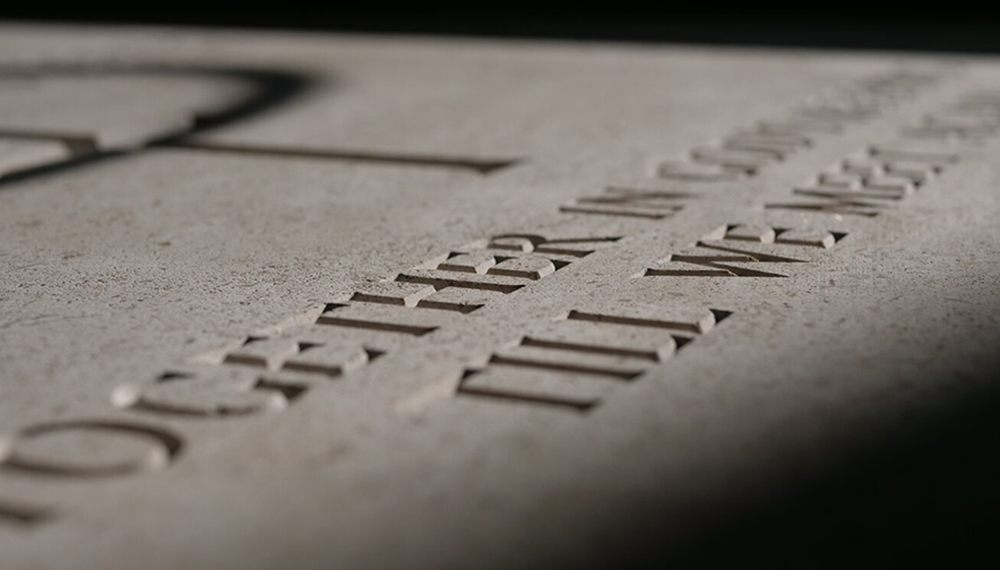

When you pause on the eleventh hour of the eleventh month you might choose to visit one of CWGC’s iconic war memorials around the world like the Menin Gate, Ottawa Memorial, Rangoon Memorial, or Delhi Memorial. Reading the many hundreds of names emblazoned onto these memorials is a particularly sobering experience.

But these times of remembrance for our Armed forces aren’t just limited to the month of November. They occur throughout the year to mark major battle anniversaries, highlight national days of importance, and offer a chance for local communities to show their respects.

The Delhi Memorial (India Gate) in India.

World War commemoration: Why it’s important

Here are five more reasons why it is important to commemorate war:

For the families

The impact of the World Wars was huge. For two generations, families in every corner of the then British Empire knew the pain of losing someone.

While no one could bring back their sons and daughters, the work of CWGC to commemorate the war dead could give people somewhere to visit and mourn their loved ones.

Half the war dead were missing by the end of the First World War.

The Commission’s decision to list the names of all the missing meant that everyone had somewhere to go and pay their respects. Whether at a grave side, or a memorial, they could see the names of those they loved.

Field Marshal Lord Plumer at the unveiling of the Menin Gate.

At the inauguration of the Menin Gate in 1927, the British commander Field Marshal Lord Plumer said to the relatives and veterans: “He is not missing; he is here.”

The insistence that everyone should have somewhere to go to find their own loved ones means that on larger memorials, like the Menin Gate, casualties with the same name have their service number added to identify each person individually.

For every family, there should be a name to find.

For the comrades

Everyone who returns home comes with their own memories and experiences of war, and much has been written about the trauma suffered by those who survived the World Wars.

For some, the Commission’s purpose became a part of their recovery. Many of the initial gardeners after the First World War were former soldiers who took therapeutic solace in the care of cemeteries and memorials.

Among them was Jack Kingston. His best friend Ernest Goodall was killed at his side during the Hundred Days Offensive. After the Armistice, Jack chose to stay behind, working in many cemeteries in the area, pictured here in 1923 visiting his friend’s grave.

Another early member of Commission staff, T. Gordon Bryceson, said: “The years spent by the staff of the Commission out in France and Belgium, following their war experiences, were a veritable God-send to most of the fellows, in that it gave them the opportunity of quietly and gradually adapting themselves to civilian life again in their various professional occupations, free of the verve strain that a direct return to city life might have put upon them.”

By the 21st century veterans of the Second World War were still returning to CWGC’s sites, making the pilgrimage to see where their comrades lie at rest.

George Batts MBE, of Maidstone, Kent landed in Normandy as an 18-year-old sapper with Royal Engineers. On returning to northern France, he said: “When we go back to France the reception is incredible… the pavements would be absolutely jammed solid with people clapping and cheering. And the number that come up to you and shake your hand and say ‘thank you’ is unbelievable.

“Go over to Normandy, go to any Commonwealth War Graves – France, Italy, wherever – and go round and look at the ages of people who were killed. And then do whatever you can for no World War to ever happen.”

For men like George, and all those who served in the World Wars and in conflicts since, commemorating war – through permanent sites of remembrance – is a signal that society will never forget their actions.

Image: Commission gardener Jack Kingston visiting his friend, Ernest Goodall’s, grave at Lijssenthoek Military Cemetery, Belgium.

For peace

The idea that commemorating war could help prevent future ones is not uncommon.

After the First World War – the so-called war to end all wars – there were many people, including King George V and Sir Fabian Ware, who publicly stated that the reminders of the cost of war could help prevent another.

While speaking at Terlincthun British Cemetery in France, King George V said: “We cannot but believe that the existence of these visible memorials will, eventually, serve to draw all peoples together in sanity and self-control.”

Even as late as 1938, with growing uncertainty about Hitler’s ambitions, Ware still believed that the Commission’s project could ultimately steer towards peace.

In a recorded address on 11 November of that year, Ware said: “Our common remembrance of the Great War is the one thing, at times the only thing, that never fails to draw our peoples together.”

These hopes that the Commission’s project would be enough to help prevent war did not, of course, come true. Yet for many, commemoration and remembrance remain a potent advocate for peace.

Image: King George V giving his speech at Terlincthun British Cemetery during the 1922 pilgrimage.

For future generations

To this day our core work of maintenance of cemeteries and memorials continues.

Alongside this is our growing role in explaining our sites to new generations. Immaculately maintained cemeteries and memorials however are nothing without visitors.

Thanks to our charity arm, the Commonwealth War Graves Foundation, we are now able to welcome thousands of volunteers to help us. They help inspect scattered graves in the UK, conduct free tours for visitors and expand our education and outreach offer.

The Foundation also funds our Interns programme, giving young people the chance to welcome visitors to some of our most famous sites and pass on the baton of remembrance.

Commemorating war is as much about caring for these sites as it is about welcoming people to understand them.

CWGF interns at the Arras Memorial in northern France.

For evermore

We are sadly reaching a time when living witnesses to the World Wars will be a thing of the past. The battle-scarred landscapes have nearly all recovered, except for a few preserved trenches and craters.

Thanks to the continuing work of generations of staff, partners and volunteers, the names of those who died in wars are still remembered more than a century after our work began.

Because of this, anyone can return to any of the 23,000 locations worldwide where a Commonwealth war grave or memorial can be found. They can make their own connection to a human part of our collective history – to discover, learn and remember a life story.

That is why it is so important that we always commemorate war.

The next generation: schoolchildren at the Plymouth Naval Memorial during the first ever War Graves Week in 2021.

Have your own World War story you want to share? Help us remember them - add your story to Evermore.