Our Architecture

From the Menin Gate Memorial in Belgium to India Gate in Delhi; from tiny cemeteries containing just a handful of graves to those with more than 11,000 burials, the Commission tends to some of the most iconic architectural structures in the world and ensures the memory of the men and women who died in the two world wars is preserved with the utmost respect.

OUR FOUNDING PRINCIPLES

"Although it is not desired that our war cemeteries should be gloomy places, it is right that the fact that they are cemeteries, containing the bodies of hundreds of thousands of men who have given their lives for their country, should be evident at first sight, and should be constantly present to the minds of those who pass by or who visit them.” Kenyon, 1918.

In the Kenyon Report, Sir Frederic Kenyon set down the overarching principles of the Commission and the architectural layout and design features for the cemeteries, including the inclusion of a ‘central feature’. It was then up to the principal architects – Sir Edwin Lutyens, Sir Herbert Baker, Sir Reginald Blomfield and Charles Holden, to undertake the actual design work.

Three cemeteries were initially chosen – Le Treport, Forceville and Louvencourt; and the task of turning these sites into permanent cemeteries fell to Blomfield. Forceville became a template for all other Commission war cemeteries.

In September 1920, The Times wrote about Forceville:

“The most perfect, the noblest, the most classically beautiful memorial that any loving heart or any proud nation could desire to their heroes fallen in a foreign land… It is the simplest, it is the grandest place I ever saw.”

ICONIC FEATURES

While no two CWGC cemeteries are the same, they often follow a similar pattern and have common features, including surrounding stone walls and wrought-iron gates. In all but the smallest cemeteries, there is a register box containing an inventory of the burials and a plan of the plots and rows. At larger sites, there is also a shelter building where the cemetery register can be found. As stated in the Kenyon report, there are also two important elements, a ‘War Cross’ designed by Blomfield and a 'Stone of Remembrance' by Lutyens.

Stone of Remembrance

Initial designs were sketched out by Lutyens after he visited some of the cemeteries with Baker and Ware in the summer of 1917. This ‘great altar stone’ as Lutyens’ referred to it, would stand as a memorial feature in the Commission cemeteries and could be used by those of all faiths and none and act as a symbol of common sacrifice.

The stone was designed by Lutyens using the classical principle of entasis – the Greek rule of optical correction used at the Parthenon, to mathematically correct the structure to make it more pleasing to the eye. Each stone is 3.5 metres in length and 1.5 metres high and it sits on three shallow steps. Lutyens employed entasis on all the horizontal and vertical edges – there are no straight lines anywhere on the structure. Should these curves be extended; they would form a series of imaginary circles over 1,800 feet in diameter.

It became known as the Stone of Remembrance and was inscribed with the words, chosen by Rudyard Kipling, from Ecclesiasticus in the Kings James Version of The Bible: ‘Their name liveth for evermore’.

Lutyens’ design had been carefully orchestrated to convoy simplicity but it was anything but simple. Such a sophisticated monument was expensive and therefore could not be reduced in size without ruining the effect. The decision was taken to only use the Stone of Remembrance in cemeteries of 1,000 burials or more – although in practice this was not always strictly followed.

Cross of Sacrifice

Kenyon, Baker and Blomfield all submitted designs to the Senior Architects Committee for a cross, Kenyon actually submitted two separate designs one of which was a Celtic wheel cross and the other which was medieval. Baker’s was a stone Christian cross which featured a bronze longsword on the front. This, Baker termed ‘the Ypres Cross’ and it also featured a small bronze image of a sailing ship, which Baker believed was emblematic of the Royal Navy’s role in winning the First World War.

Blomfield’s approach was different and allied him more closely with the thinking of Lutyens. Like Lutyens’ Stone of Remembrance, Blomfield’s ‘War Cross’, as it was originally called, was to be the other permanent element of all the Commission’s cemeteries.

In his memoirs, Blomfield wrote:

“What I wanted to do in designing this cross was to make it as abstract and impersonal as I could, to free it from association with any particular style, and, above all, to keep clear of any of the sentimentalities of Gothic. This was a man’s war too terrible for any fripperies, and I hoped to get within range of the infinite in this symbol of the ideals of those who had gone out to die.”

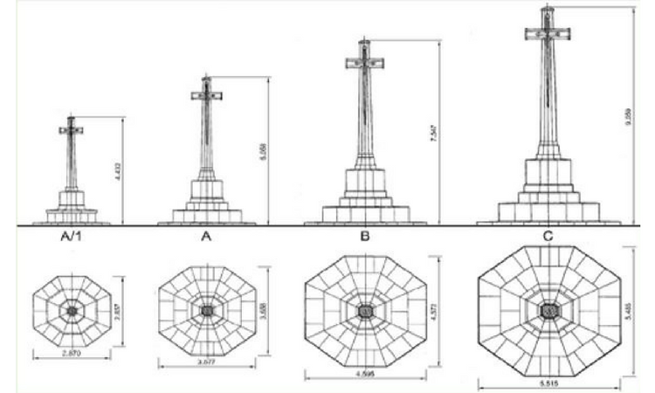

Designed by Blomfield in white stone, it has proportions that place it close in terms of general aesthetic to the Celtic cross. The short cross arms, fairly close to the top of the shaft, are designed to be exactly one-third of the length of the shaft. The shaft is tapered using the optical correction technique of entasis and both the shaft and cross arms are octagonal.

The Cross was designed to be flexible in allowing for four versions, each one of a different height – 14 feet, 18 feet, 20 feet and 24 feet.

The base is octagonal and allowed further flexibility in the design meaning that the whole structure was capable of being incorporated into walls or allow for seating features at its base.

The position of the Cross varies enormously from cemetery to cemetery.

By 1937, more than 1,000 crosses had been erected in France and Belgium alone.