Commemorating D-Day

On 6 June 1944, the Allies landed on the beaches of Normandy, and the battle to liberate France from German occupation began. 75 years later, the cemeteries of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission stand as permanent reminders of Operation Overlord. Constructed across the former battlefields, today they are places of peace and reflection, telling the stories of those who fought and died.

“NOS A GULIELMO VICTI VICTORIS PATRIAM LIBERAVIMUS”

“We, once conquered by William, have liberated the Conqueror's native land"

Inscription on the CWGC Bayeux Memorial

Join us in Normandy for The Great Vigil

Join us as we carry our flame of commemoration to Normandy. We will illuminate each CWGC grave and pay tribute to those who lost their lives at D-Day and in the Battle of Normandy.

Find out moreCreating the cemeteries

Commandos ready to disembark on Sword Beach, 6th June 1944.

On the morning of D-Day, 500 men of 48 (Royal Marine) Commando came ashore on Juno Beach. They suffered heavy casualties as they dragged themselves out of the water under fire from above, but they fought on. Over half of their number became casualties, with 40 dead.

Over the next few days, the survivors of 48 Commando returned to the sands of Juno Beach and collected the bodies of their comrades. They created a little cemetery in a garden near the beach and buried 80 men there: Commandos and Canadians, sailors and soldiers. They crafted crosses from wood scavenged from the bombed-out houses nearby and placed the much-respected green beret on the graves of the commandos.

The 48th Royal Marines Commando Cemetery at Berniers near Courseulles, Normandy.

Throughout the Battle of Normandy this difficult task was carried out countless times. In the aftermath of fighting, crosses or upturned rifles would appear. In contrast to the First World War, the British Army of the Second World War was well prepared and organised to deal with the dead. Each unit had its own ‘burial officer’ who was charged with arranging for graves to be dug and burials recorded. It was a macabre task that was deeply upsetting to perform, but it was ultimately vital for the morale of those left behind.

Archive photo of Graves Concentration Unit admin, Normandy.

Information about burials was then passed to Army Graves Registration Units (GRUs). No.32 GRU was responsible for much of the area around Bayeux. The unit arrived in Normandy on 11 June 1944 with 30 men and set up an office in Bayeux, and immediately began to work through reports from unit burial officers in the field, visiting the graves, and creating a formal register. In early August, a shipment of unpainted, pressed and galvanized metal crosses arrived, and these were used extensively to replace the rough wooden crosses and upturned rifles across the battlefields.

Bayeux War Cemetery

The 79th General Hospital at Bayeux, 20 June 1944.

British medical facilities were established in Normandy soon after D-Day, and on 24 June hospitals were established in tents on the outskirts of Bayeux. Over the following months thousands of men were treated. A remarkable survival rate of 93% was achieved by the skilled and dedicated doctors, surgeons and nurses but not all of those brought for treatment could be saved.

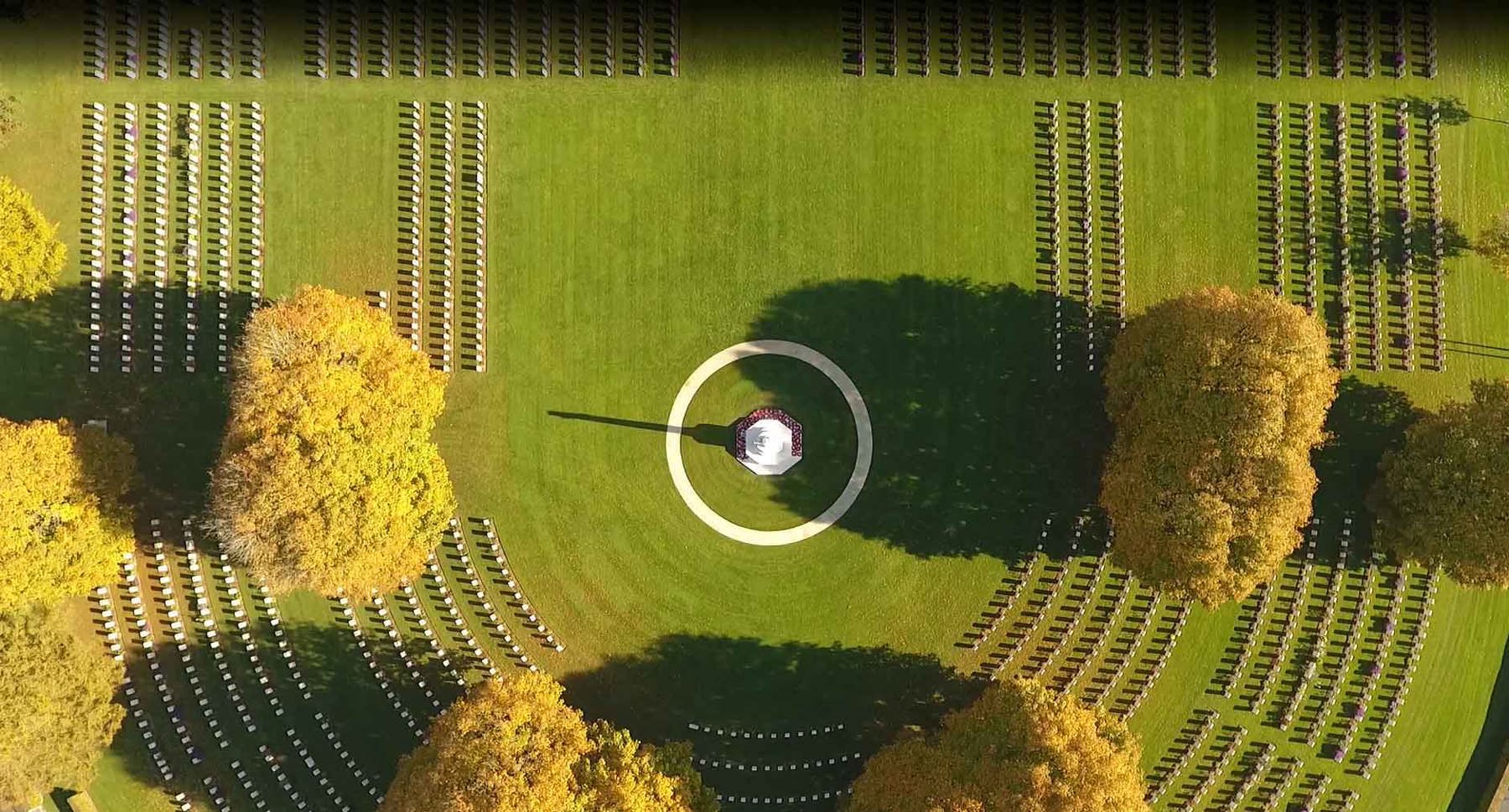

On 1 July 1944, No.32 GRU taped out the outline of a cemetery in a field on the outskirts of Bayeux, intended to be used by the nearby hospitals. The first burials were made in early July and soon hundreds of graves had been dug by labour units and French civilians. Originally, space was marked out for more than 5,600 graves, but ultimately only five plots in what would become known Bayeux War Cemetery were filled with those who had succumbed to wounds or illness. Most of the burials would be brought here by Graves Concentration Units (GCUs).

Archive photo of Graves Concentration Unit, Normandy checking crosses.

Several GCUs worked across Normandy throughout late 1944 and 1945. Their task was to continue the work of the Graves Registration Units by disinterring the remains buried in isolated graves or small cemeteries and rebuying them in permanent cemeteries: a process known as ‘concentration’.

Working closely together, GRUs and GCUs selected locations for the construction of permanent cemeteries and began the long and often horrific task of creating the cemeteries we see today. In October 1944, the first representatives of the Imperial War Graves Commission (IWGC) arrived in Normandy, to advise the Army Graves units on the formation of the nascent cemeteries.

In December 1944, GCU officers and men arrived at the little 48 Commando cemetery made just after D-Day near Juno beach. The remains were taken to Bayeux War Cemetery and today almost all the 48 Commando dead of D-Day are buried together in Plot XIV. Rows A and B.

Bayeux War Cemetery taken just before headstone installation.

The Commission appointed Philip Hepworth as the principal architect for the cemeteries of north-west Europe, and Hepworth travelled across the former battlefields in late 1944, ensuring that burials continued in line with his plans for the cemeteries. At Bayeux, space was allocated for the construction of shelter buildings and the iconic Stone of Remembrance and Cross of Sacrifice. On 17 November 1947 Bayeux War Cemetery was passed into the perpetual care of the IWGC.

Thanks to the work of burials officers, Graves Registrations Units and Graves Concentration Units, there were relatively few ‘missing’ of the battle of Normandy, especially when compared to the great battles of the First World War. Nevertheless, a memorial was required to commemorate those who died during Overlord but had no known grave – including those who could not be identified, or whose bodies could not be recovered. Among them were nearly 200 men lost when the MV Derrycunihy which sank off Sword Beach on the morning of 24 June 1944 after striking a German mine dropped by the Luftwaffe during the night. Most were members of the 43rd (Wessex) Division’s armoured reconnaissance regiment.

Bayeux War Cemetery is now the final resting place of more than 4,100 Commonwealth servicemen, of whom nearly 340 remain unidentified. Also buried here are some 500 servicemen of other nations, including more than 460 Germans. More than 750 of those buried or commemorated at Bayeux died on D-Day, and some 600 over the following five days. More than 1,000 died in the first two weeks of August.

Today, Bayeux is a place of pilgrimage for thousands of people each year. Since the late 1940s, War Graves Commission staff have worked tirelessly to ensure that the Commonwealth cemeteries across Normandy remain beautiful and peaceful final resting places, safeguarding the memory of those who fought and died here. A Latin inscription on the Bayeux Memorial reads: “We, once conquered by William, have now liberated the Conqueror’s native land.”

Ranville War Cemetery

In early June, airborne units began to use the open field adjoining Ranville Churchyard as a burial place, and it became known as the ‘Airborne Extension Cemetery’. After the fighting was over, remains were brought here from across the battlefields. Today, most of the dead of the 6th Airborne Division from D-Day and the weeks that followed can be found here.

Located near the famous Pegasus Bridge, this is the final resting place of 2,400 servicemen, making it the third largest CWGC cemetery in Normandy. In 1947, a party of relatives made a pilgrimage here, and were met by locals who had lined their path with candles and were told by the mayor that: ‘they were not leaving their men folk like strangers buried in a foreign land, but like angels of deliverance sleeping among friends they had come to deliver’.

When you approach the elegant entrance building, pause to see the way the cemetery’s architect, Philip Hepworth, designed the arch to frame the Cross of Sacrifice. Many of the original burials are at the front of the cemetery, while the men buried here later can generally be found towards the rear, near the shelter building with its high colonnade.

Go on a virtual visit to Ranville War Cemetery

Beny-sur-Mer Canadian War Cemetery

The Canadians suffered more than 1,000 killed and wounded on D-Day. Almost all their dead from 6 June can be found in Beny-sur-Mer Canadian War Cemetery. Begun in late 1944, graves were brought here from across the battlefields and several temporary cemeteries. Now the final resting place of more than 2,000 servicemen, the cemetery is planted with maple trees.

You approach the graves through a wide grass avenue of trees, before reaching the Stone of Remembrance which is inscribed in both English and French. You can climb up the Norman-style towers which flank the stone and look out towards Juno Beach in the distance. Walking through the cemetery, you will see the maple leaf symbol of Canada on almost every headstone, along with the names of the historic regiments of the country and inscriptions chosen by families, sometimes in French.

Many brothers joined the Canadian forces together. While they were often assigned to separate units to fight, the process of burial and concentration brought many back together in death. There are nine pairs of brothers buried here, along with one group of three brothers: George, Thomas and Albert Westlake, from Toronto.

Go on a virtual visit to Beny-sur-Mer Canadian War Cemetery

Ryes War Cemetery

The most westerly of the three Commonwealth beaches, Gold was assaulted by the 50th (Northumbrian) Infantry Division. The first assault troops of the Hampshire, Dorset, East Yorkshire and Yorkshire regiments landed at 7.25 am, along with amphibious tanks of the 8th Armoured Brigade. Fighting together, the tanks and infantry broke through the German beach defences and pushed inland.

In the days that followed, the 50th Division advanced, liberating several French villages. A medical aid station was established near the village of Bazenville, and a small cemetery was close by, then known as ‘Gold Beach Cemetery’. It was later expanded with graves brought from elsewhere and is now the final resting place of more than 870 servicemen, including over 270 Germans.

Ryes War Cemetery is set in open countryside and retains a remarkable feeling of bucolic peacefulness. Two stone pergola flank the Cross of Sacrifice, dividing the cemetery in two. In summer they are covered with bright flowers in bloom. At the rear of the cemetery Philip Hepworth designed a small and intimate shelter building of cream stone.

The 50th Division suffered 400 casualties on D-Day but only a handful of those who died on Gold Beach are buried in Ryes. Most were eventually laid to rest in Bayeux War Cemetery, including almost 60 men of the 1st Hampshires. Landing on the western end of Gold Beach, the battalion immediately came under intense machine gun and mortar fire as they crossed the dunes. Nevertheless, they secured their objectives over the course of the day, including the coastal commune of Arromanches at 9pm.

Hermanville War Cemetery

The village of Hermanville was taken on D-Day by the 1st South Lancs, who were still covered in sand. Just one kilometre inland, this was originally known as ‘Sword Beach Cemetery’. Many of those who died during the landings at Sword and the drive inland over the following few days are now buried here, although most of the graves were relocated from a temporary site called ‘Hermanville Beach Cemetery’ in the summer of 1944.

Today, Hermanville War Cemetery is the final resting place of 1,000 servicemen; 100 remain unidentified. There is a large red triangle on the ground just outside the entrance: the symbol of the British 3rd Division. As you walk into the cemetery, the path is surrounded by informal planting and gives the impression of moving from the grassy dunes into a garden. Many of the trees have been recently replanted, but in time the cemetery will regain the feeling of a woodland glade. The chapel-like shelter building was designed by Philip Hepworth. Look out for the ornate weathervane.

Jerusalem War Cemetery

The smallest of our Normandy cemeteries, Jerusalem War Cemetery can be found near the village of Chouain, a little south of Bayeux.

Chouain was the site of a German counterattack in the days following the invasion, as an armoured column was dispatched to recapture Bayeux. Of the 47 burials here, 24 are men of the Durham Light Infantry – among them, Private Jack Banks who, at 16 years old, is the youngest casualty of the invasion we commemorate.

The cemetery itself is small but perfectly formed, with three, gently curved, rows of headstones facing a cross of sacrifice. You will find the registry box installed in a stone seating area, a place to stop, sit, and spend a moment to pay tribute to those commemorated here.

Go on a virtual visit to Jerusalem War Cemetery

Leave your own Legacy

A gift in your will can help us continue telling those stories for generations to come, so their sacrifice is not forgotten.

SHARE THE STORIES OF D-DAY AND NORMANDY

Visit For Evermore: Stories of the Fallen, our online commemorative resource to read and share the stories from some of the people who took part in D-Day and the Normandy Campaign.

All images © IWM unless otherwise indicated.