The Great Escape

Made famous by the 1963 Hollywood movie, one of the most well known stories of the Second World War is the escape by Allied prisoners of war from Stalag Luft III. Known as The Great Escape, this story has a tragic ending. Discover more about the men who attempted escape and their commemoration by CWGC.

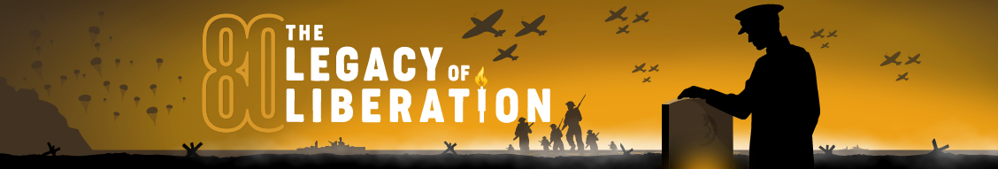

German guards on duty by one of the watch towers at Stalag Luft III, Sagan. (© IWM)

STALAG LUFT III

Stalag Luft III was a German POW camp for Allied airmen in Sagan, in modern day Poland. Established in March 1942, at its peak it held almost 11,000 Commonwealth and American enlisted men and officers in several compounds across a 60-acre site, overseen by 800 guards.

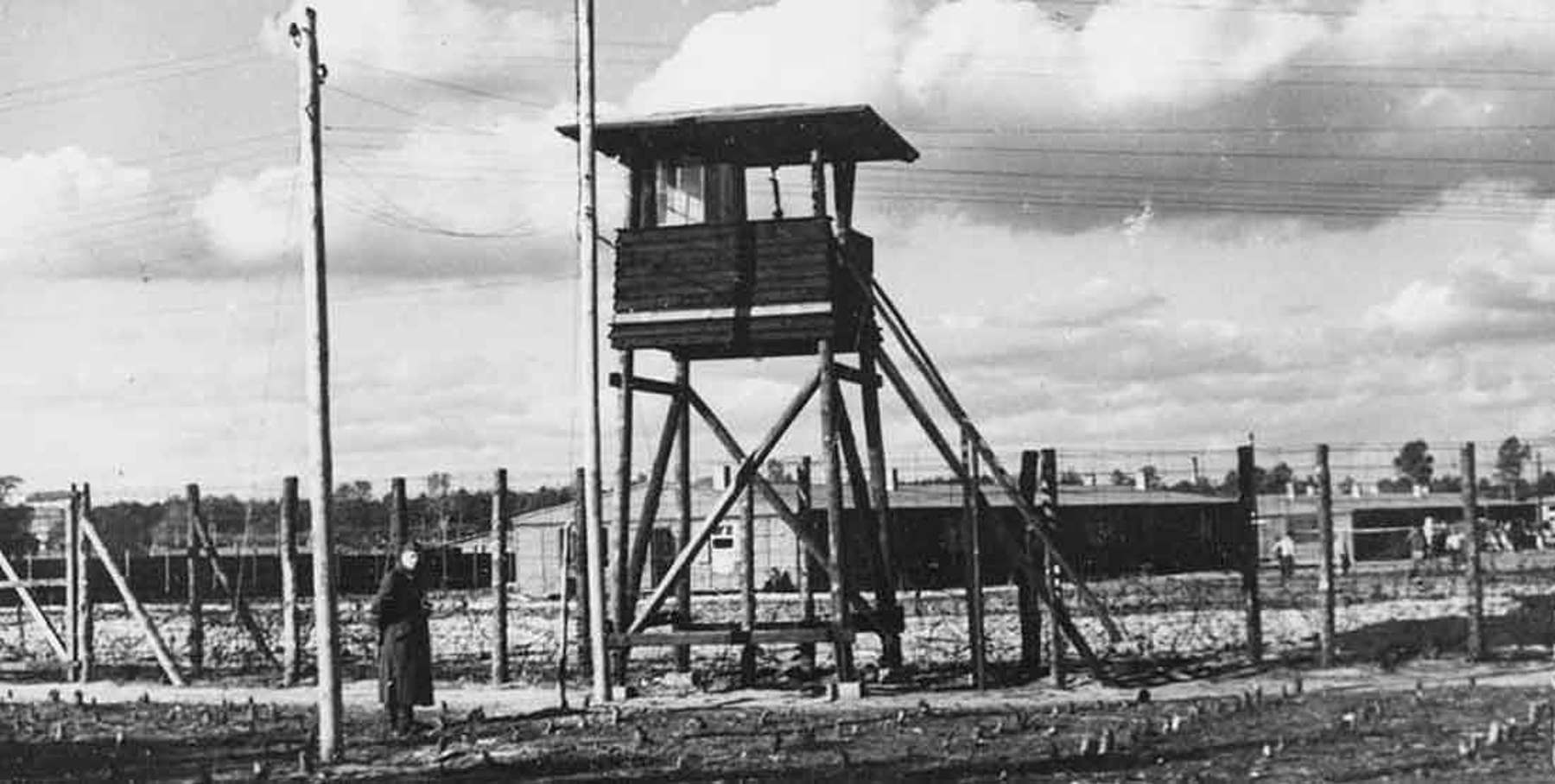

The camp was known for being more comfortable than many, with generally good relations between the guards and the POWs. Compounds were allowed a sports field, and the camp had a well-stocked library and even a POW orchestra.

British prisoners of war tend their garden at Stalag Luft III. (© IWM)

The Germans went to great lengths to make escape as difficult as possible. Huts were raised off the ground and the entire camp had been constructed on sandy soil to make tunnelling extremely hazardous. Many POWs who had already attempted to escape from other camps were sent to Stalag Luft III due to these extra security precautions.

It was from Stalag Luft III that 200 men would attempt to escape on the night of 24 March 1944, in what became known as the ‘Great Escape’

‘Everyone here in this room is living on borrowed time. By rights we should all be dead! The only reason that God allowed us this extra ration of life is so we can make life hell for the Hun…’

Squadron Leader Roger Bushell (Big X), mastermind of the Great Escape, 1943.

THE GREAT ESCAPE

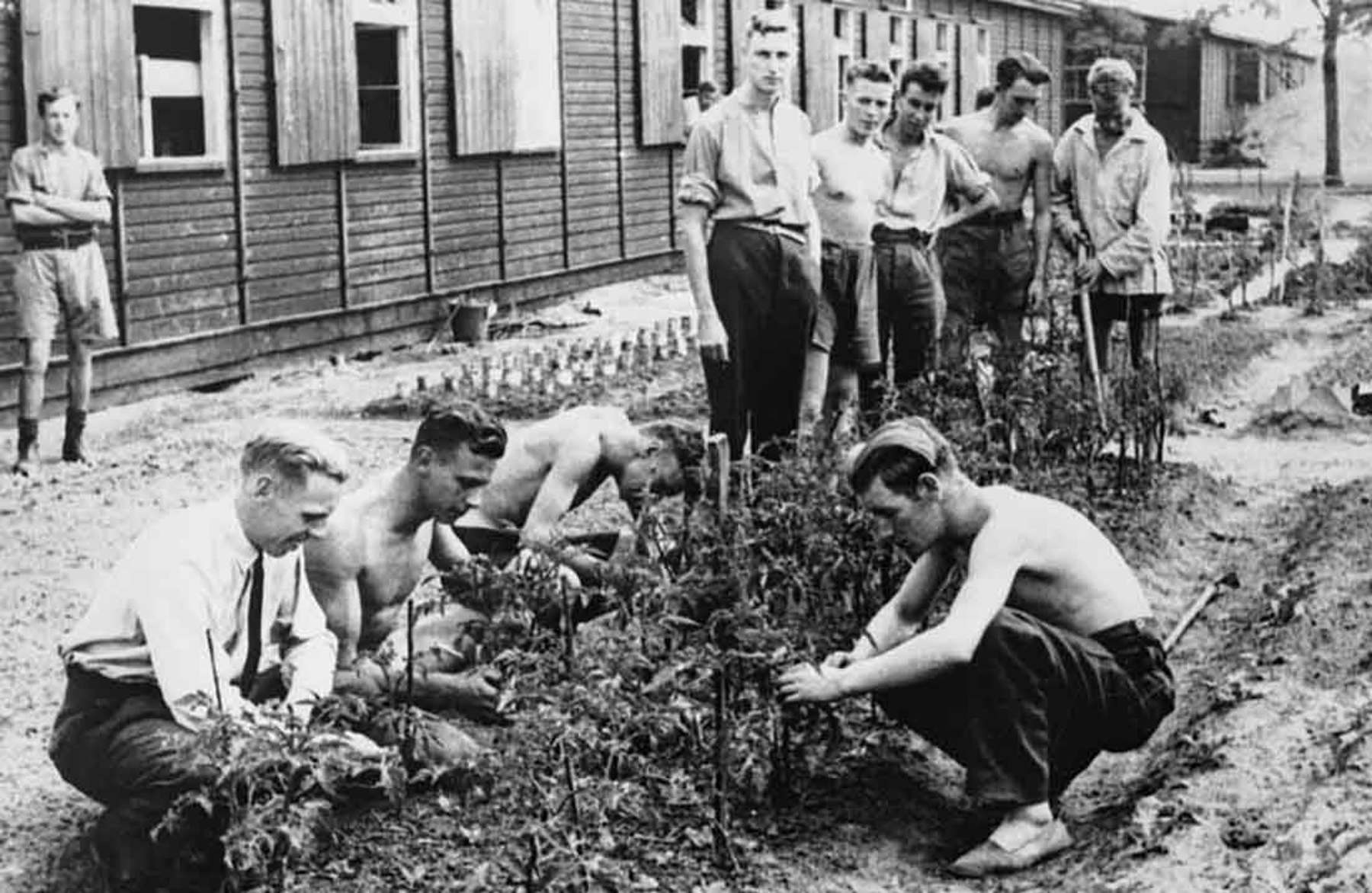

Meticulously planned for many months, the escape from Stalag Luft III was the single largest breakout from a German POW camp during the war. Three tunnels codenamed ‘Tom’, ‘Dick’ and ‘Harry’ were dug under the wire from within the prison huts. Over 600 POWs worked in shifts to excavate the tunnels, while others surreptitiously disposed of the soil and collected materials to assist the work. At the same time, civilian clothes were fashioned, while official papers were forged or acquired from guards.

The Germans were aware that work was taking place. ‘Tom’ was soon discovered and destroyed, and ‘Dick’ had to be abandoned when the Germans began building on the expected exit location. Work on ‘Harry’ continued, however, and after a year was completed.

The Harry escape tunnel with German guards after the escape. (© IWM)

The 2ft wide tunnel was nearly 30ft deep and extended more than 330ft out of the camp. 200 men were selected to take part, and on the moonless night of 24 March 1944, the escape began. Seventy-six men escaped, but the seventy-seventh man was spotted and the alarm was raised.

After the escape, the Germans were horrified to discover that 4,000 bed boards were missing and had been used to shore up the tunnels. Many other items had been used, including 90 complete bunk beds, 635 mattresses, 52 twenty-man tables, 10 single tables, 34 chairs, 76 benches, 69 lamps, 246 water cans, 30 shovels, 1,000ft of electric wire, 600ft of rope, and 3424 towels.

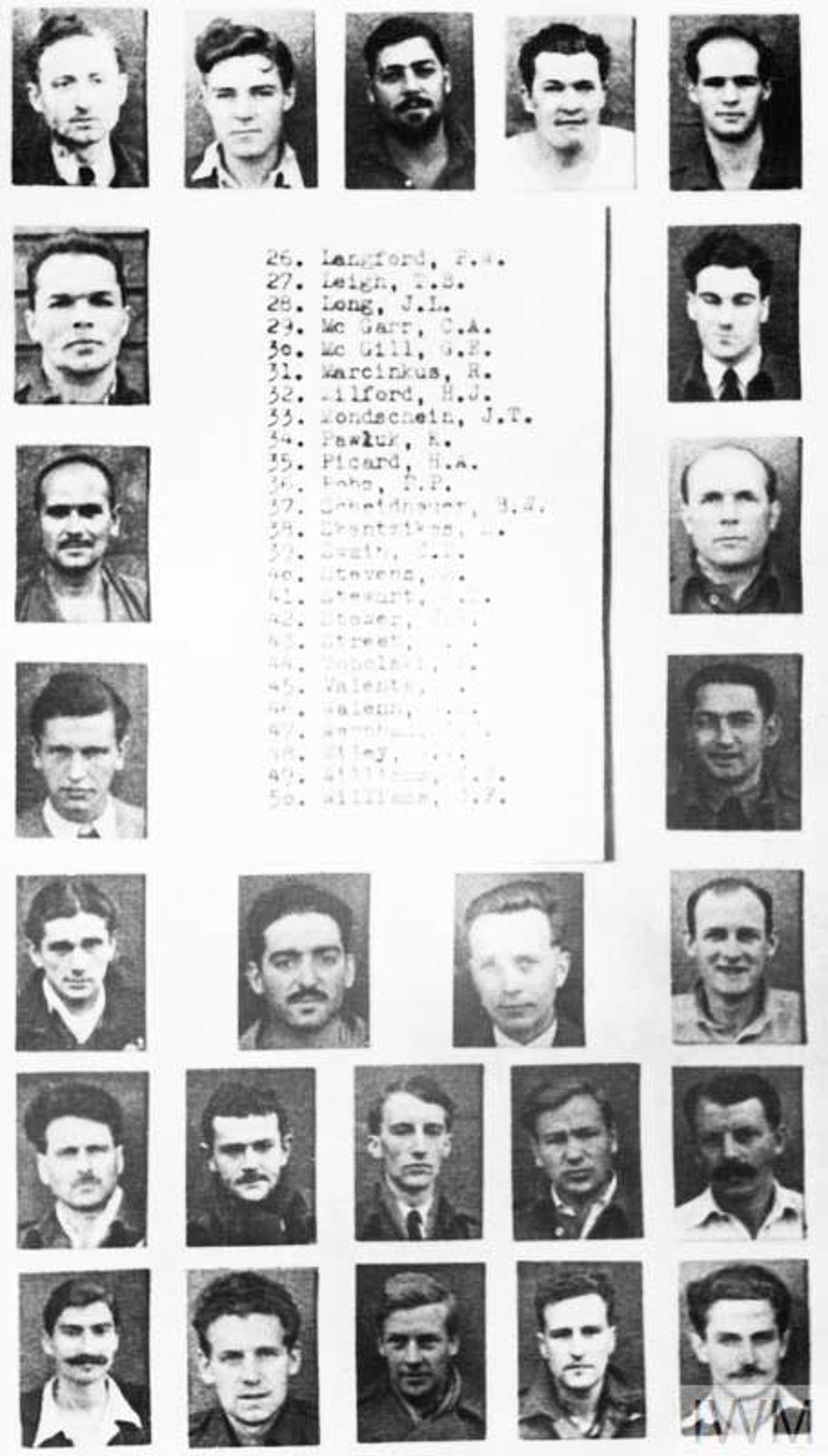

Photographic set of 25 of the 50 Great Escapees (© IWM)

Although they had managed to escape the camp, liberation did not last long for most of those involved. All but three of the escapees were recaptured over the following weeks and held in prisons across Poland and Germany.

Adolf Hitler ordered that they should all be shot, along with the camp commandant of Stalag Luft III, the camp architect, and all the guards on duty at the time of the escape.

A number of senior Nazi officials argued against this, but ultimately fifty Great Escapers were executed to deter others from future escape attempts.

Over the next few weeks, the selected POWs were murdered individually or in small groups. Their bodies were then cremated.

Learn more about Poznan in World War 2.

Commemorating the Great Escapers

The memorial built at Stalag Luft III by POWs to commemorate the executed Great Escapees. It was designed by Australian-born architect Wylton Todd. (© IWM)

The cremated remains of the Great Escapers were returned to Stalag Luft III. The newly-appointed camp commandant was appalled by the killings and allowed the prisoners to build a memorial to house the ashes.

In 1948, a Royal Air Force search team travelled to the camp to collect the ashes. They found that the memorial had been broken into, and a large number of the urns were smashed. Apparently, passing soldiers believed that gold had been hidden in the urns. The ashes of all but two of the fifty who had been executed were buried in CWGC Poznan Old Garrison Cemetery.

Find more information on Poznan (Old Garrison) Cemetery

Help us keep alive the stories of those who died in the World Wars

A gift in your will can help us continue telling those stories for generations to come, so their sacrifice is not forgotten.

SHARE THE STORIES OF THE GREAT ESCAPE

To find out more about some of the people involved in the Great Escape, you can read and share the fascinating stories of the Great Escapers on For Evermore: Stories of the Fallen, our online commemorative resource.

All images © IWM unless otherwise indicated.