08 February 2023

Behind enemy lines: The story of the Chindits & Operation Longcloth

80 years ago, a unique Commonwealth force stalked the steaming jungles of Burma. Join us for a retrospective on Operation Longcloth and the exploits of the Chindits.

Operation Longcloth

Burma overrun

Chindits of the Long Range Penetration Group wade through a deep Burmese river (© IWM)

December 7th, 1941 is a day that will long live in infamy, to paraphrase former US President Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

The Imperial Japanese Navy had launched a surprise aerial assault on the US naval base at Pearl Harbour, catching the United States completely by surprise.

But it wasn’t just Pearl Harbour that came under attack. Imperial Japanese forces launched a series of campaigns throughout the Asia Pacific region on that day.

Just two weeks after its early December onslaught, the Empire of the Rising Sun had captured Hong Kong from the British Empire.

By the 8th of February 1942, Singapore had fallen.

Rangoon, the capital of Burma (present-day Myanmar), was captured by the Japanese in March.

British and Commonwealth forces stationed in Burma withdrew over 1,000 miles across the border to India. This remains the longest retreat in British military history.

The situation in the Far East in 1942 and early 1943 was dire. British and Indian Army efforts to regain ground in Burma were repeated studies in frustration.

The first concerted British/Indian offensive following Rangoon’s capture occurred in the 1942-43 dry season. It achieved little beyond the loss of important equipment and many casualties.

The Japanese were thought of as invincible, able to traverse the rugged mountain ranges and hot, dense jungles of Burma with ease. They could seemingly endure massive hardships, inhospitable terrain, and live off the land.

British High Command required a strategy rethink. If the Japanese could make the jungle their ally, why couldn’t they?

Enter an unconventional commander with unconventional ideas.

Brigadier Orde Wingate

Image: A unique commander, Brigadier Orde Wingate specialised in incursion force tactics (© IWM)

Image: A unique commander, Brigadier Orde Wingate specialised in incursion force tactics (© IWM)

Brigadier Orde Charles Wingate came from military stock.

Wingate’s father, Colonel George Wingate, had served for over 20 years in the Indian Army. His father’s cousin, General Sir Reginald Wingate, was also governor-general of Sudan between 1899-1916 and would hold the same post in Egypt up until 1919.

With this background, Wingate was destined for a career in the army.

After his private schooling, Wingate joined the Royal Artillery’s officer training school, the Royal Military Academy, in Woolwich, South London.

Wingate completed his officer training in 1923. He was promoted to Lieutenant in 1925. By 1928, he was serving in the Sudan Defence Force (SDF) in East Africa. He covered most of the journey from Europe to Africa to get to his Sudanese posting by bicycle.

While serving in Sudan, Wingate relished his time spent out in the bush and field with his troops, preferring to be out under the stars and in the open than behind a desk. This would come to inform his military philosophy.

Flash forward to 1940. Wingate is serving in East Africa under General Archibald Wavell, British Command-in-Chief of Middle East Command.

Beginning to explore guerrilla tactics, Wingate had formed a unit called Gideon Force with Wavell’s approval. Gideon Force was a mixed British, Sudanese, and Ethiopian force that went on far-ranging patrols behind enemy lines in the desert to disrupt supply columns and gain intelligence.

Gideon Force was disbanded in June 1941. While active, the force of 1,700 men and officers had caused chaos for their Italian adversaries, even forcing the surrender of over 20,000 Italian soldiers.

The blueprint, a small, light infantry-led force penetrating behind enemy lines to disrupt and harass the enemy, had been designed. Soon, it would be tested in an entirely different theatre of combat.

The Long Range Penetration Group

Men of the Long Range Penetration Group out on patrol (© IWM)

Wingate had been a fan and proponent of unconventional military tactics, but he also had an unconventional personality for a British Army officer. He held a rebellious streak and was not afraid to speak his mind or criticise his superiors.

Feeling unappreciated by High Command after the successes of Gideon Force, as well as feeling his men had been mistreated, Wingate had written a highly scathing report upon the unit’s winding up.

He was quickly demoted from Colonel to Major and transferred to join Wavell in the Far East.

General Wavell had been swept out of Africa and the Middle East following successive defeats to German General Erwin Rommel’s Africa Corps. While in Asia, Wavell requested Wingate’s services.

Wingate arrived in Burma in March 1942. While there, he undertook a survey of the Burmese countryside to better understand where he’d be fighting and how and how the Japanese had adapted to it.

Wingate did all this while the British were retreating into India.

After presenting his findings and proposals to Wavell in Delhi in May 1942, the Long Range Penetration Group was given the green light.

The Long Range Penetration Group would:

- March into Burma’s jungles on foot

- Target enemy communication and supply lines

- Disrupt the enemy in any way they could

- Get supplied by air

- Use close air support instead of heavy artillery

The soldiers of the Long Range Penetration Group were nicknamed the Chindits, a corruption of chinthe, the Burmese word for “lion”.

Who were the Chindits?

Image: Chindit badge, portraying a Chinthe, a mythical beast, guardian of Burmese Temples (© IWM)

Image: Chindit badge, portraying a Chinthe, a mythical beast, guardian of Burmese Temples (© IWM)

The first Chindit group was formed in the summer of 1942 under the name of the 77th Indian Infantry Brigade.

Half the unit’s men were British, including the 13th Battalion of the King’s Liverpool Regiment and the men of the 142 Commando Company. Joining them were the 3rd Battalion of the 2nd Gurkha Rifles and the 2nd Battalion of the Burma Rifles, made of Burmese, Indian and Nepalese soldiers.

The Chindits were made up of eight columns of around 306 men. Gurkha columns were slightly larger with 356 soldiers. Each column was made up of:

- An infantry rifle company equipped with nine Bren guns and three 2-inch mortars

- A heavy weapon support group equipped with four Boys anti-tank rifles, two medium Vickers machine guns and two light anti-aircraft guns

- A reconnaissance platoon with scouts from the Burma Rifles

- A sabotage group from 142 Commando

- An RAF liaison officer for supply drops and air support

- A doctor

- A radio detachment for inter-column communications

Each column was also assigned around 60 mule handlers and 120 mules to help carry their supplies and equipment.

The units had to be self-supporting, highly mobile, and able to act on their own initiative deep in enemy-held territory.

Throughout 1942, the men learned jungle warfare in the thick rain forests of Central India during monsoon season.

The idea was to acclimatise them, especially the British elements, to intense, unforgiving jungle conditions.

The Chindits endured some of the toughest training ever meted out to British and Commonwealth troops. By 1943, they were deemed ready for active field operations.

A major British offensive into Burma that the Chindits had originally meant to support had been cancelled. However, General Wavell gave the go-ahead for the unit to enter the field anyway.

Operation Longcloth was a go.

Into Burma: Operation Longcloth begins

Chindits sabotaging a railway. Cutting Japanese communication links was a top priority (© IWM)

The first Chindit patrol crossed over the Burma/India border at Imphal on 8th February 1943.

3,000 men formed the expedition. They were split into two groups:

- 2 Group (Northern) led by Brigadier Wingate

- 1 Group (Southern) led by Major Bernard Fergusson

Operation Longcloth’s objective was to disrupt and disable Japanese lines of communication. In particular, Burma’s railways were choice targets for the Long Range patrolmen.

Ahead of their mission, Brigadier Wingate addressed his men:

“Today we stand on the threshold of battle. The time for preparation is over, and we are moving on the enemy to prove ourselves and our methods…. We need not…. as we go forward into the conflict, suspect ourselves of selfish or interested motives. We have all had the opportunity of withdrawing are we are here because we have chosen to be here… we have chosen to bear the burden and heat of the day.”

Upon crossing the border, the seven Long Range Penetration Group columns met little to no resistance.

Going was tough: rivers had to be forged; dense jungle had to be cut through; hills and peaks had to be traversed.

Contact with the Japanese

The Chindwin River was crossed on the 13th of February.

Two Chindit columns marched south. The southern was meant to deceive the Japanese into thinking it was part of a larger offensive, allowing the remaining columns to push eastward.

One British soldier with the Southern Group was decorated like a general to heighten the perception that this was a main attacking force. They were resupplied by air during daytime to reinforce the ruse.

The first Japanese troops the Chindits faced were on the 15th. Sporadic jungle clashes occurred but the full strength of the Chindits remained concealed.

Imperial Japanese officers and troops didn’t know the numbers facing them. Five Chindit columns were able to slip eastward while the Southern Group kept their opponents engaged.

Confusion reigned amongst the Japanese. The Chindits managed to distract a 15,000-strong enemy division, leaving outposts and important railway bridges open to attack.

Over 200 Japanese troops had been killed during the Chindits’ early operations.

The two southern columns were due to swing east at the beginning of March to attack Burma’s main north-south railway.

One was able to forge a path through the jungle, cutting down foliage with machetes, and sabotage rail bridges. The second column was ambushed and retreated over the border into India.

Wounded Chindits

Despite spreading massive confusion, and disrupting enemy operations, the Chindit columns were taking heavy casualties.

Diseases such as malaria and dysentery were also as deadly to Long Range patrolmen as Japanese bullets and bayonets.

A big problem was what to do with the wounded.

Before heading out, Brigadier Wingate ordered all wounded to be left behind.

While this was not strictly followed, many men were left in jungle villages or where they fell. They would either die of their wounds, succumb to tropical diseases, or meet their fate at the hands of the Japanese.

Many Chindits subsequently have no known grave.

Crossing the Irrawaddy River: a river too far?

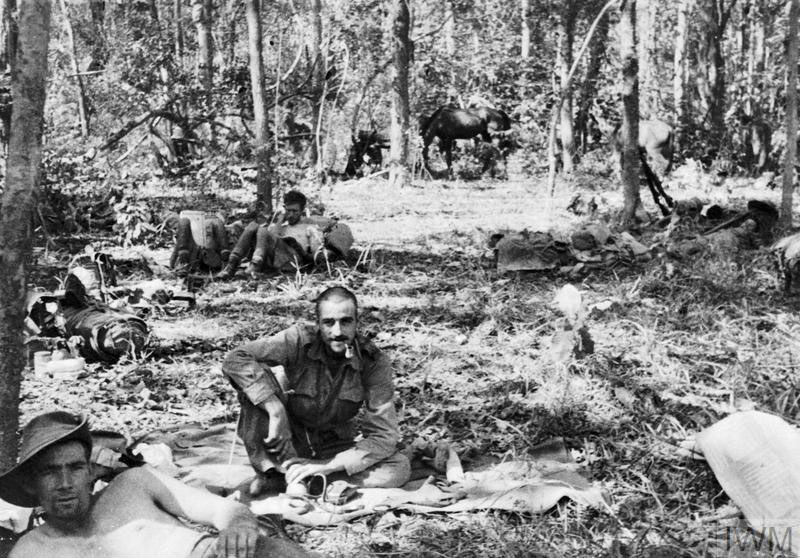

Patrolmen take a brake. Campaigning in the Burmese jungle was tough for even the highly-trained Chindits (© IWM)

After the March railway attacks, Wingate ordered the Chindits to cross the Irrawaddy River. Fergusson’s columns went over first, with Wingate’s group crossing on the 18th of March.

At first, the terrain across the river appeared navigable. As the columns progressed, however, it was anything but.

In his diaries, Major Fergusson recorded his experience after crossing the Irrawaddy:

“The next few days of marching were desperately thirsty and only the strictest water discipline got us through them. The soil was red laterite and the jungle low dry teak; the only life that flourished there was red ants, with the most vicious sting imaginable.

“They would stand on their heads and burrow into you as if with a pneumatic drill. If you were unlucky enough to brush a tree with your sleeve, you would spend the next 15 minutes in a torture compared to which the martyrdom of Saint Sebastian was a holiday with pay.”

Access to water was restricted. Insects were crawling all over the unwashed Chindits. What’s more, their boots and uniforms were becoming ragged and worn, offering little protection from the elements.

The Japanese had also twigged the Chindits were being supplied by airdrop. They were starting to box the Long Rage Penetration Group into a jungle prison.

A series of roads in the area over the Irrawaddy also meant Japanese forces could quickly traverse terrain to hunt their elusive opponents.

By late March 1943, the game was up. With terrain proving nearly insurmountable, and Japanese pressure mounting, Wingate ordered most of his columns to retreat to India.

One column was ordered to push further eastward, although there were already at the limits of air supply.

Crossing back over the Irrawaddy proved difficult. Imperial Japanese observers and patrols littered the riverbank. They could quickly concentrate on an area where an attempted Chindit river crossing was reported.

Gradually, the Long Range columns split up into groups, returning back to India in drips and drabs.

Wingate’s HQ unit was the first to arrive but for others, it sometimes took weeks and months to reach safety. Part of one column made it to southern China. Another group withdrew to Northern Burma. Others weren’t so lucky, either being captured or killed.

By the end of April 1943, Operation Longcloth was over.

Was Operation Longcloth a success?

After three months on patrol in inhospitable terrain behind enemy lines, the Long Range Penetration Group had covered more than 1,500 miles.

The effectiveness of their actions was hard to judge.

The Chindits had infiltrated enemy territory, they had damaged railway connections, they had inflicted casualties on the enemy and proved Allied soldiers could fight effectively in the jungle.

One railway connection, linking Mandalay to Myitkyina was put out of action for a month. Entire Japanese divisions were diverted away from frontline duties to hunt the Chindits.

The propaganda value of Operation Longcloth was high, especially as the British and Indian armies had faced constant setbacks in the Far East since the Japanese invasion of 1941.

The advances in airdrops and supplies were also noted, as was the need to improve the evacuation of the sick and wounded on further Chindit patrols.

Chindits cross another river in Burma (© IWM)

One unintended consequence of Operation Longcloth was that it showed the Japanese that areas of the Burmese countryside previously thought unnavigable could actually be traversed.

As such, the Imperial Japanese Army tried its own mass incursion tactics later in the war, although without the air support required to be effective.

For British military planners, the question of the Chindits’ effectiveness boiled down to resources.

Was it worth taking men out of their parent units, spending months training them, and sending them out on far-reaching patrols? Could the time and equipment be better spent reinforcing existing forces?

General Bill Slim, one of the British’s most effective World War Two commanders and hero of the war in Asia, wrote:

“The Chindits gave a splendid example of courage and hardihood. Yet I came firmly to the conclusion that such formations, trained, equipped, and mentally adjusted for one kind of operation were wasteful.

“They did not give, militarily, a worthwhile return for the resources in men, materiel, and time that they absorbed… Special forces were usually formed by attracting the best men... The result of these methods was undoubtedly to lower the quality of the rest of the Army"

Another problem was Wingate. His orders and plans in the field were often changed on the fly. Men under his command thus felt many missions had little to no strategic value and led them on long pointless excursions into the jungle.

Despite these misgivings, one person who was convinced of the Chindits’ effectiveness was Prime Minister Winston Churchill.

Churchill gave his approval, along with other British commanders, for an expanded Chindit mission into Burma in 1944.

Further Chindit operations

Image: Lieutenant George Cairns VC was killed on patrol during Operation Thursday, the second major Chindit operation

Image: Lieutenant George Cairns VC was killed on patrol during Operation Thursday, the second major Chindit operation

Operation Thursday gathered six Long Range Penetration brigades, starting in March 1944.

Around 10,000 men were sent into the jungle, some landing by glider or parachuting into designated landing zones, to continue the long-rage operations the Chindits were famous for.

They continued to spread confusion amongst the Japanese and disrupt their supply and communication lines. Ferocious hand-to-hand fighting between bayonet and katana stained the jungle red.

Lieutenant George Cairns won the Victoria Cross after leading his men against a Japanese attack after losing his arm to a sword-wielding Japanese officer, characterising the nature of up-close jungle warfare.

Lieutenant Cairns is buried in Taukkyan War Cemetery

Orde Wingate held command of the Chindits until his death on the 24th of March 1944. He was travelling in an overladen plane which crashed into the tree-covered hills of Manipur in Northeast India. At the time of his death, Wingate had reached the rank of acting Major-General.

Command of the Chindits was transferred to Brigadier Joe Lentaigne. The unit was officially disbanded in February 1945.

Commemorating the Chindits

The Rangoon Memorial. Soldiers commemorated on the memorial have no known grave.

The lightly armed and equipped Chindits took heavy casualties during their major operations.

Operation Longcloth had set out with 3,000 men. By the time they returned to India in April 1943, a third had been killed, captured, or succumbed to diseases.

Of the 2,200 or so men that made it back, a further 600 were too debilitated to return to active service.

After Operation Thursday, the Long Range Penetration Group lost nearly 1,400 killed and 2,400.

The Commonwealth War Graves Commission commemorates fallen Chindits in our cemeteries and memorials in Myanmar. These include:

- Rangoon Memorial

- Rangoon War Cemetery

- Taukkyan War Cemetery

- Taukkyan Memorial

- Thanbyuzayat War Cemetery

The Chindits also have a non-CWGC memorial in London, with a special section dedicated to Orde Wingate.

Learn more stories of the Fallen with Commonwealth War Graves

Our search tools can help you uncover more stories of those commemorated by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission.

Use our Find War Dead tool to search for specific casualties by name, where they served, which branch of the military they served in, and more parameters.

Looking for a specific location? Use our Find Cemeteries & Memorial search tool to find all our sites. You can search by country, locality, and conflict.