09 February 2023

Best WW1 battlefields to visit - a guide

Interested in visiting where fighting took place during the Great War? Here’s our guide to some of the best WW1 battlefields to visit.

Your guide to visiting WW1 battlefields

Welsh Guardsmen sit in a reserve trench waiting for action at the Somme, one of WW1's most infamous battlefields (© IWM Q 4416)

Where are the battlefields of WW1?

Picture a WW1 battlefield. You’re probably thinking of a location somewhere in northern France, with two lines of opposing trenches and No Man’s Land in between.

The most commonly thought of World War One battle sites are in France and Belgium, i.e., the Western Front.

This region was subject to intense, bloody fighting between 1914-1918 and is usually the place history enthusiasts head to when visiting WW1 battlefields.

But the Great War was a truly global event. World War One battlefields can be found worldwide, from Africa to Asia and many locations in between.

Fighting in Europe was not restricted to France and Belgium. Italy was a key theatre where men fought the elements as much as themselves high in the Alps or in deep ravines and valleys.

For example, the often overlooked war on the Eastern Front was a huge conflict, engulfing millions of men and women from the Russian Empire, Austro-Hungary, the Balkans and Imperial Germany.

From the Middle East to China to Africa, the Great War touched all corners of the globe. However, in this article, we will mostly be focusing on the major battlefield sites of the Western Front.

When to visit World War One battlefields

The Thiepval Memorial to the Missing of the Somme on a glorious July day.

Battlefields of the Western Front tend to be accessible throughout the year.

When you go is really up to you, where you plan on visiting, and your general itinerary. Depending on your budget, it’s best to spend to 2-5 days visiting and studying historic regions around France and Belgium.

If you were to go in the autumn or winter, however, you might want to pack a coat and some waterproof boots! It can get wet and snowy during that time of year. Indeed, the service personnel engaging in trench warfare often had to do so in appalling weather.

Spring and summer should bring plenty of sunshine, but still bring an umbrella in case of seasonal showers.

You may also wish to visit these sites on the anniversary of a particular battle. For example, a trip to the Somme battlefields could be timed around early July, when the battle began.

Likewise, remembrance services will be taking place in the second week of November in accordance with the signing of the Armistice.

Important information

Image: A pile of rusted munitions found near the battlefields of Passchendaele. If you come across such objects on a World War One battle site, do not interfere with them as they are potentially dangerous (Wikimedia Commons)

Image: A pile of rusted munitions found near the battlefields of Passchendaele. If you come across such objects on a World War One battle site, do not interfere with them as they are potentially dangerous (Wikimedia Commons)

When visiting WW1 battle sites, it is important to remember these were active fields of conflict. Millions of shells, grenades, and bullets were expended during the Great War. Many unexploded shells and other potentially deadly items lurk beneath the fields and pastures of the Western Front.

Each year, during ploughing season, farmers throughout the former battlefield regions dredge up tonnes of rusting shells. You may see them piled high on the sides of roads. These are left for the Army to collect and dispose of safely.

If you do see them, please do not pick them up or take them home as souvenirs. People are still killed by these instruments of death a century after the fighting ended. Leave them for professionals.

Likewise, if you see any areas cordoned off or spot any no-entry signs on old battlefields, respect them. It could help you avoid injury or death.

Best WW1 battle sites to visit

The best WW1 battle sites to visit will depend entirely upon your interests and connection with different periods of the war.

France and Belgium are full of old battlefields and Great War sites, for example. From the magnificent Menin Gate in Ypres through to Beaumont-Hamel and Thiepval on the Somme, World War history is everywhere.

Are you interested in learning more about the Indian Army’s experience on the Western Front? You may wish to visit Neuve-Chappelle. The memorial there commemorates over 4,700 Indian labourers and servicemen who fought in France.

Want to learn more about the ANZACs in France and Belgium? You may wish to visit one of our memorials or cemeteries commemorating New Zealand and Australian troops.

Belgium WW1 battlefields

The Menin Gate stands over the route hundreds of thousands of Commonwealth troops took to reach the battlefields of the Ypres Salient.

Belgian World War One battlefields saw combat from the war’s earliest salvoes.

WW1 battle sites in Belgium include:

- Liège – The Siege of Liège took place on 4th August 1914, making it the first battle on the Western Front. German forces besieged the city, taking it from the Belgian army on 16th

- Namur – Namur was captured during the initial German offensive on Belgium on 25th It would not be liberated until 1918.

- Brussels – The Belgian capital was captured on 20th November 1914 and was liberated on 18th November 1918, a week after the Armistice was signed.

- Mons – Mons was the site of the first clash between the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) and the German Military on 23rd August 1914. It is also reputedly the site of the final shots of the war on the Western Front on November 11th, 1918.

- Ypres – The City of Ypres became a focal point for fighting in Belgium and is the site of several of the much-storied WW1 battles.

Ypres

Ypres, now called Ieper, was the sight of bitter fighting throughout the war. The First Battle of Ypres occurred in October 1914. Two more significant actions would take place there during the Great War, including the now infamous battle at Passchendaele.

It is also home to the Menin Gate, under which hundreds of thousands of Commonwealth troops passed on their way to battlefields around Ypres.

The CWGC Ieper Information Centre contains more information about the casualties of the Ypres battles. Make sure you pay us a visit if you’re taking a battlefield trip to Belgium.

Battlefields in France WW1

Visiting WW1 battlefields in France will take you mostly to the country’s northern departments.

The Western Front stretched from the coast to the border with Switzerland. Some of the key Great War battlefield locations to visit in France include:

- The Somme – The Somme department and river saw terrific fighting throughout the war, particularly during 1916 when the five-month Battle of the Somme raged between July and November.

- Verdun – Verdun is emblematic of French resistance, determination, and sacrifice during World War One. The Western Front’s longest battle took place in the fortress city between February and December 1916 with massive loss of life.

- Marne – The Marne River was the site of one of the war’s most significant battles, with the French Army and BEF halting Germany’s sweep into France, preventing the fall of Paris.

- Arras – Arras, one of the great cities of Northern France, was the site of two major battles in 1914 and 1917. The CWGC Visitor Centre is close to Arras – a must-visit for any trip to French WW1 battle sites.

- Cambrai – Cambrai is notable for being the site of the first major tank battle in history.

- Aisne – The battlefields of Aisne saw action throughout the Great War from its opening year to the final bitter fighting in 1918.

- Vimy Ridge – Vimy Ridge in the Pas-de-Calais is the site of a major victory for the Canadians.

WW1 battlefield tours

Several tour operators offer World War 1 battlefield tours of the Western Front and the sites of World War One battles.

At the CWGC, we instead organise tours of our war cemeteries and memorials in the UK, France, and Belgium.

Learn more about our war grave tours near you and how you can get involved.

Battles of WW1 - discover the history

Major battles of WW1

WW1 naval battles

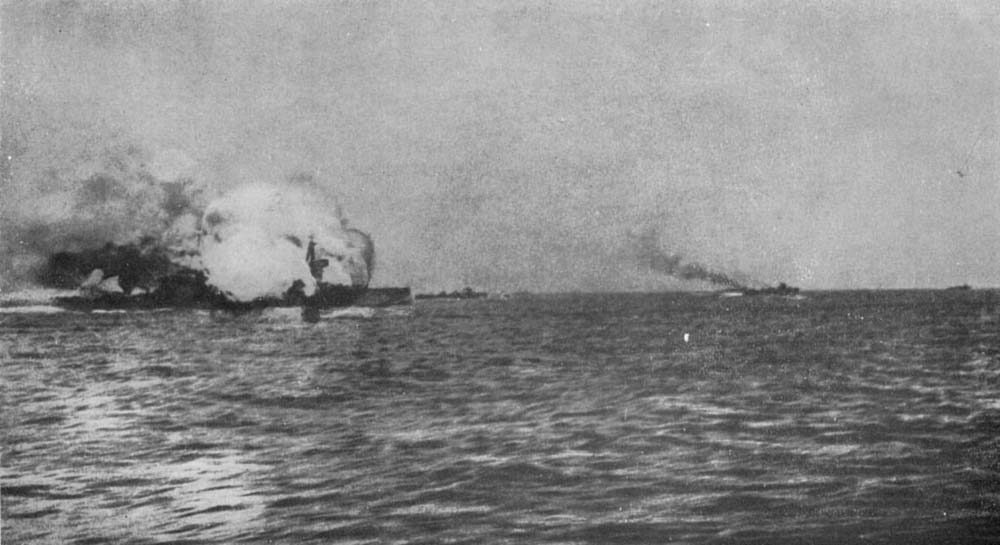

HMS Invincible blows up after taking shell damage during the Battle of Jutland (Wikimedia Commons)

Often when we think of WW1 battles, we think of the grinding, brutal static warfare on the Western Front.

However, the Great War wasn’t just fought on the land. It was fought in skies around the globe and fought on and below the waves of the world’s oceans.

Part of the prelude to World War One had been a naval arms race. Britain had introduced a new class of battleship in 1906, the Dreadnought, that effectively made other rival powers’ fleets obsolete overnight.

Imperial Germany spent vast sums developing its High Seas Fleet to match the technological and power projection capabilities of the Royal Navy. It was eager to use its new ships during the war.

WW1 naval battles took place in seas and oceans that covered the globe. During the 1910s, several European powers still had empires, thus requiring navies to help connect their territories and police their waters.

As such, naval conflicts happened in the Atlantic, Pacific, and Indian Oceans as well as in the seas around Africa and the Mediterranean.

These varied from single ship-to-ship encounters to knockout slugfests between large fleets.

Perhaps the most famous naval battle of World War One is the Battle of Jutland.

The battle was fought between the 31st May-1st July 1916 in the North Sea near Jutland. The forces involved were Germany’s High Seas Fleet under the command of Admiral Reinhard Scheer and the Royal Navy’s Battlecruiser and Grand Fleets.

British naval forces at Jutland were commanded by Admiral David Beatty and Admiral Sir John Jellicoe.

Jutland was a confused, frantic, and bloody affair.

The goal for the German Navy was to weaken the Royal Navy’s North Sea presence with an ambush on the Battlecruiser Fleet.

However, British codebreakers were able to decipher the High Seas Fleet’s plans and put both its North Sea squadrons out to sea to meet the German threat.

Over 250 ships and 100,000 men were involved in the Battle of Jutland.

In the battle's opening phases, the German High Seas Fleet managed to inflict several losses on their British rivals.

Admiral Beatty’s flagship, HMS Lion, was damaged. HMS Indefatigable and HMS Queen Mary were both sunk. Beatty withdrew to allow Jellicoe’s Grand Fleet to catch up.

Admiral Scheer was now outnumbered and heavily outgunned. The High Seas fleet turned to steam back to its home ports on Germany’s northern coast. It wouldn’t leave harbour for the rest of the war.

This allowed the Royal Navy to blockade German ports for the remainder of the war, exposing Germany’s economic vulnerabilities.

The Royal Navy had lost 14 ships sunk and more than 6,000 naval personnel at Jutland. German losses came to 11 ships and 2,500 men. The difference was that the Royal Navy was able to put more ships and men to sea the following day. The German High Seas Fleet simply didn’t have the numbers of men or ships to compete.

The nature of Great War naval battles means the bodies of the fallen have been lost at sea. As they have no known grave, Commonwealth naval casualties are commemorated on our naval memorials at Chatham, Plymouth, and Portsmouth.

Merchant navy casualties are commemorated on the name panels of the Tower Hill Memorial in London.

Trench battles WW1

A German observation post showing how developed the Imperial German's trench fortifications were during the Great War (© IWM Q 57538)

If there’s one aspect of the WW1 battlefields that capture the public imagination, it’s the trenches.

Trench warfare began in the first year of the war. The war’s opening stage was one of manoeuvre, but with no side gaining a clear advantage, trench networks began to form across the Western Front.

Very quickly, it emerged that what were hoped to be temporary structures became permanent.

Some of the German trenches would eventually become several metres deep with concrete bunkers and bunkhouses. Allied trenches were not as deep, overall, nor as sophisticated.

By the war’s end, the trenches stretched from the French and Belgian coast to the Swiss border, although not in a single continuous line.

Image: Men of the Australian 4th Division at Passchendaele advance through a reserve trench (© IWM E(AUS) 825)

Image: Men of the Australian 4th Division at Passchendaele advance through a reserve trench (© IWM E(AUS) 825)

Frontline trenches were supported by a spider’s web of service and supply trenches. These could stretch back for several miles. If you were unfamiliar with your position, it could be very easy to get lost. Soldiers put up signposts with ironic names like Piccadilly Circus to aid navigation.

Life in the trenches was dangerous and harsh. While they offered some protection, the threat of cave-ins from artillery fire was constant. Stick your head over the parapet, and a sniper’s bullet could find you.

Additionally, with little cover, trenches would fill with rainwater, sleet, and snow. Drainage was primitive, often just men bailing out water as fast as possible with their hats and helmets.

Rats, lice, and other pests also got in. Trenches could become rubbish dumps, with ammo boxes, food waste, and other forms of detritus piling up, even corpses of soldiers and their service animals. Men got used to living in squalor, although troops were rotated regularly.

Between opposing trench lines was No Man’s Land: often a blasted landscape of shell craters, barbed wire, corpses, and more horrors. Each side would set up machine gun posts to overwatch the killing ground between trenches.

If you were lucky enough to survive going “over the top” and made it to the enemy's position, then trench warfare would descend into intense close-quarters combat. Numerous weapons would be used to clear trenches: grenades, bayonets, cudgels, pistols, trenching tools, and shotguns.

Trench warfare was a grim affair for everyone involved, but it represented the harsh reality of fighting on a Western Front Great War battlefield.

Of course, trench warfare was not the only form of combat practiced during World War One. This was a truly global conflict, taking in fighting in mountains, grand set-piece battles on the Eastern Front, small-scale skirmishes in Africa, and wars of rapid manoeuvre in the Middle East.

Want more stories like this delivered directly to your inbox? Sign up for our newsletter for regular updates on the work of Commonwealth War Graves, blogs, event news, and more.

Sign UpBattle of the Somme WW1

Aerial photo of Pozieres, 1916. Artillery fire from the Battle of the Somme obliterated the village (© IWM Q 63990)

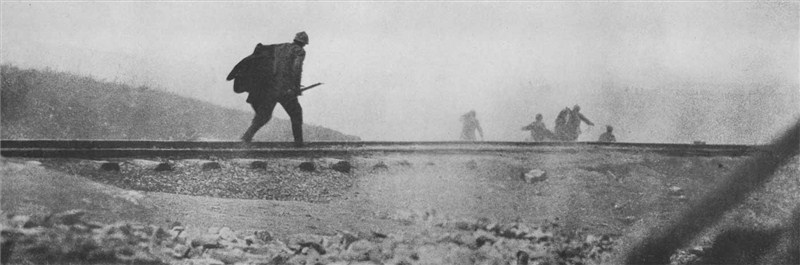

The Battle of the Somme is a notorious World War One battle. It was certainly one of the bloodiest campaigns of the war.

Running for five months from July-November 1916, the carnage along the Somme would result in over a million casualties. Both the Entente Allies and their German opponents suffered terribly.

The Battle of the Somme was conceived to break 18 months of trench warfare and take the pressure off the French. At the time, the Battle of Verdun, another meatgrinder of a campaign, was underway, draining the French Army of manpower.

July 1st, 1916, the battle’s opening day, was black and bloody for the British and Commonwealth forces. On this one morning, the British Army took nearly 58,000 casualties, of which just over 19,000 were killed. It remains the worst loss of life in a single day sustained by the British Army in its history.

A typical Somme battlefield resembled the imagery we associate with Great War sites: barbed wire, crater scarred No Man’s Land; opposing trench systems peppered with machine-gun posts.

Like many major World War One offensives involving the British, the Somme was fought not just by UK-born soldiers. Servicemen came from all over the Empire, including Ireland, India, South Africa, Australia, New Zealand, Newfoundland, and Canada.

Image: British soldiers advance into No Man's Land in a still taken from the "Battle of the Somme" film (© IWM Q 70167)

Image: British soldiers advance into No Man's Land in a still taken from the "Battle of the Somme" film (© IWM Q 70167)

Despite the enormous loss of life, the British and Commonwealth forces took a strip of land just 6 miles deep and 20 miles long.

The Somme battlefield did offer some positives. Improvements were made in infantry and artillery tactics and their combined use. The men who fought at the Somme, on the British side, were also mainly conscripts. The fighting helped whip them into a battle-hardened force.

Tanks were also used sparingly for the first time during the Battle of the Somme, although they did not prove to be the decisive breakthrough weapons the Allies hoped they would be.

The fighting on the Somme covered a wide area, incorporating many locations in Northern France.

Today, we have many cemeteries and memorials commemorating those who fell in the five-month campaign.

The most iconic of our Somme memorials is likely the Thiepval Memorial to the Missing. Over 70,000 men who died during the Battle of the Somme, but who have no known grave, are commemorated on its name panels.

Battle of the Marne WW1

German soldiers prepare to attack during the Battle of the Marne, 1914 (Wikimedia Commons)

In August, the guns of the Western Front had fired their opening salvoes, signalling the start of the bloodiest conflict Europe would experience to date.

Now, the fighting was heating up across the continent.

6th September 1914. The Imperial German Army had been sweeping through France and Belgium, taking large swathes of land. The capture of Paris, part of the German Army’s ambitious Schlieffen Plan, was a real possibility.

Opposing the German advance, commanded by Chief of Staff Helmuth von Moltke, where the French under General Joseph Joffre and their allies from the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) commanded by General Sir John French.

The BEF was a tiny force compared to the French and German military, which could put millions of men into the field. Britain's standing professional army reached only 250,000 or so soldiers and officers at the start of the war.

On the morning of the 6th of September, 150,000 French soldiers launched an attack on the German right flank. The Germans had crossed the Marne River days before but had overrun their supply lines. They were also exhausted from their rapid advance across Northern France.

German forces wheeled to meet the French offensive. A 30-mile gap in the German lines was created and quickly flooded with French troops and men from the BEF.

Fighting raged until the 9th of September. Eventually, the Entente powers pushed back the advancing Imperial German Army.

The Battle of the Marne was a stark warning of the cost of life the Great War would eventually claim, culminating in a combined loss of 250,000 men on both sides in just three days.

The battle has also been dubbed the “Miracle of the Marne”. Despite the huge loss of life, with the, in particular, BEF taking a high percentage of casualties relative to its size, the victory halted the German advance.

Legend has it that upon hearing of the situation on the Marne, General von Moltke is said to have told German head of state Kaiser Wilhelm II, “Your Majesty, we have lost the war.”

While the Marne battle helped avoid the capture of Paris and the collapse of the French Army, it did mean World War One would continue. Millions more men and women would lose their lives over the coming four years.

Battle of Ypres WW1

The ornate Cloth Hall in ruins after First Battle of Ypres (© IWM Q 57288)

The Ypres Salient, like the Somme, is one of the most iconic World War One battlefields.

Situated in West Flanders, the historic city of Ypres was the site of three separate, devastating campaigns. The small city had long been a centre of commerce and industry, famed for its intricate cloth work. The magnificent medieval Cloth Hall stood proudly in Ypres’ city centre as a symbol of its pride and prosperity.

By the end of the war, Ypres and its Cloth Hall would lie in ruins.

So how did Ypres become a WW1 battlefield? How and why was the Ypres Salient established?

It all began following the Battle for the Marne. With the German push into France checked by the French Army and the BEF, both powers began the “Race to the Sea”. This was essentially an effort to protect each army’s flanks by pushing along to the French and Belgian coasts.

Imperial Germany had previously invaded Belgium as part of its grand sweep into France, capturing the important port city of Antwerp.

As both sides headed for the coast, they continued to build the trench networks that would be emblematic of a typical WW1 battlefield.

In the dance of manoeuvring armies heading for the sea, Ypres and its fortifications were a choice strategic target.

The area around the city, which would become the Ypres Salient, overlooked transport routes to Belgian coastal ports. These were vital for keeping the large armies supplied.

The First Battle of Ypres took place in October 1914. In response to the capture of Antwerp, French and Belgian forces had pulled back to Ypres. They were soon reinforced by the BEF. Between 8-19th October, the city streets were gradually filled with Allied troops.

The fighting began in earnest on October 19th. A German offensive was launched at Langemark to Ypres’ north. Comprised of “Kindercorps” soldiers, young recruits fresh from training, the German forces took heavy casualties against the arrayed British and Commonwealth troops.

Further attacks between the rest of October and November resulted in the capture of Messines Ridge overlooking the city and its surroundings by the German Army.

The First Battle of Ypres came to a halt on November 22nd, 1914. The city remained in Allied hands.

As with any major World War One battle, casualties were high. German casualty estimates run as high as 130,000. The French took upwards of 85,000 losses while the BEF took around 58,000 men killed, missing, or wounded. Belgian casualties came to just over 21,500.

Lines drawn from the British side at Menin to the German-occupied Roulers would become known as the Ypres Salient.

Ypres would be the site of further bitter fighting across the war, such as the Second Battle of Ypres in early 1915. This is notable for seeing the first use of gas on a WW1 battlefield by German forces assaulting Canadian positions outside the city.

Today, the Ypres (Menin Gate) Memorial stands as a testament to the huge loss of life that took place in and around Ypres. Over 50,000 Commonwealth service personnel are commemorated there.

Battle of Verdun WW1

French soldiers advance into the carnage of Verdun (Wikimedia Commons)

No discussion of World War One battle sites would be complete without Verdun.

Between February-December 1916, the French City, known for its network of star forts from 19th-century wars, was the target of a battle specifically designed to “bleed the French to death”.

The city held symbolic value for both sides. Verdun had been the last city to fall in France’s humiliating defeat to Prussia in the 1870s. It also had been the location of the medieval treaty that broke up the Carolingian Empire and formed the core of what would later become Germany.

The Verdun battlefield became a black morass of fighting and death. More than a million men on the French and German sides fought over the city. Of the 800,000 casualties of the battle, over 300,000 would die.

Verdun had been formulated by German General Erich von Falkenhayn as a battle of attrition. He wanted to tie up and kill as many French soldiers in one place as possible.

A staggering 2.5 million artillery shells were moved to German frontlines, feeding more than 1,300 artillery pieces when the battle began on 21st February 1916. Over the next ten months, Verdun would become the definition of a Great War meat grinder.

Image: The opening of the Douaumont Ossuary. It holds the bones of thousands of unknown casualties of the Battle of Verdun (Wikimedia Commons)

Image: The opening of the Douaumont Ossuary. It holds the bones of thousands of unknown casualties of the Battle of Verdun (Wikimedia Commons)

France’s dogged resistance, coupled with the Battle of the Somme requiring a redistribution of troops by Imperial Germany, turned Verdun into a brutal stalemate. The Russian Brusilov Offensive on the Eastern Front also caused consternation for the Germans, pulling troops away, allowing the French to reinforce and go from the defensive to the offensive.

By October, the French Army had recaptured the important Fort Douaumont. One of the key fortifications in Verdun, the Germans had taken the fort in February. Its recapture was a signal the tide was turning.

The final decisive blow came in December with the French capture of Hill 304. The bloodbath at Verdun was finally over.

As Verdun was primarily a French/German showdown, the CWGC has no major memorials or cemeteries commemorating the battle’s casualties. Instead, the French built a huge battlefield ossuary to hold the remains of its unidentified casualties.

Battle of CambraI

British tanks captured near Bourlon during the Battle of Cambrai (© IWM Q 29943)

Today, tanks and armoured fighting vehicles are a common sight in battles and conflicts around the world. Prior to the Battle of Cambrai, these armoured beasts were rare on WW1 battlefields.

The Battle of Cambrai, which took place between late November to early December 1917, was the first time tanks had been used en masse on a battlefield.

476 tanks had been assembled by the British in secret on the eve of the battle. Joining them were 1,000 artillery pieces, eight infantry and five cavalry divisions.

Once the tanks got rolling on 20th November after a terrific artillery barrage, they managed to punch straight through the German lines and advance five miles. Such gains had rarely been seen since the Western Front had descended into Trench warfare in 1914.

A German counterattack on the 30th of November reversed those hard-fought gains. The battle would rage for a week or so more before the exhausted forces on both sides called a halt to the fighting.

Cambrai is notable not just for its introduction of mass tanks. It was the way the armour, infantry, artillery, and aerial support all interlinked that was important. World War One battlefields like Cambrai gave birth to some of the tactics and strategies that continue to inform warfare to this day.

Around 80,000 servicemen were killed, went missing, or were wounded during the battle.

Today, the Cambrai Memorial is a focal point for the commemoration of this revolutionary battle. It bears the names of more than 7,000 British and South African servicemen who died in November and December 1917 but have no known grave.

Battle of Passchendaele

Wounded Canadians & German Prisoners cross the muddy ground at Passchendaele (© IWM CO 2196)

One of the defining characteristics of the image of WW1 battle sites is mud.

The sucking, cloying, sticky mud, churned up by shell blasts, strewn with barbed wire, corpses, and craters, was another enemy for soldiers to overcome.

Ahead of the Battle of Passchendaele, the heaviest rains for 30 years had turned the ground in and around the Ypres Salient into a quagmire. Even the tanks of the Royal Armoured Corps struggled to get through the mud.

The Battle of Passchendaele was one of the final phases of the Third Battle of Ypres. Its goal was to seize the Passchendaele Ridge ahead of Ypres and drive the Germans out of the Salient.

British, Australian, and New Zealand troops were given this difficult task. If German machine guns and artillery weren’t hard enough to combat, the arrayed Allied forces would have to advance through thick mud.

In places, the mud was deep enough to rise to the ankles. Falling into shell holes and drowning was a very real danger. Such was the fate of many of the men commemorated on memorials to the missing.

The Third Battle of Ypres, prior to the Passchendaele offensive, had been raging since July 1917. It had already claimed hundreds of thousands of lives. The first blood banks had been set up by the Royal Medical Corps in anticipation of the high number of casualties expected from the assault on Passchendaele.

Following zero hour at 5.25 am on 12th October, the Royal Artillery let fly with its big guns. Once again, the mud dampened their effect. Guns would sink into the mud due to the recoil. Any shells that landed on German positions often sank deep into the ground before detonation, dampening their explosive impact.

Some minor advances were made during Passchendaele’s opening stages, but swift German counterattacks reduced the gains.

Facing the Allies across the morass of No Man’s Land were concrete pillboxes, machine gun nests, and uncut barbed wire. Advancing in some sectors was all but impossible. The attack was called off on October 13th. A second Passchendaele offensive would take place two weeks later on October 26th.

Despite only lasting one day, the Battle of Passchendaele resulted in a heavy death toll for the British and Commonwealth forces involved.

Total British Empire casualties are estimated at 13,000 killed, wounded, or missing.

For the New Zealand Division, Passchendaele was an especially black day. During a disastrous attack on an area called the Bellevue Spur, the Division was hit for 2,700 casualties, more than 840 of which were killed.

The October 12th attack on Bellevue Spur is still the highest single loss of life in New Zealand’s military history.

WW1 battle casualties

World War One battlefields were especially deadly when compared with the conflicts of the past.

The advantage lay in defence. Modern weapons like heavy artillery and especially machine guns, coupled with trench networks and No Man’s Land, made attacking a costly endeavour for all armies.

The total number of combat deaths stands at roughly 8,000,000 combined:

- 6 million – Entente Powers & allies

- 2 million – Central Powers & allies

Total deaths of Great War service personnel by all causes, such as wounds or disease, sits between 8,500,000-10,000,000:

- 1 - 6.4 million – Entente Powers & allies

- 8 - 4.3 million – Central Powers & allies

We commemorate just over 1,000,000 casualties of World War One at the Commonwealth War Graves Commission. By member state, they are approximately split by:

- United Kingdom – 837,000

- India – 74,000

- Canada – 65,000

- Australia – 62,000

- New Zealand – 18,000

- South Africa – 11,500

Those who fell on World War One battlefields commemorated by the Commission can be researched using our Find War Dead tool. Discover their stories today.

WW1 battlefields today

The former battlefield of Verdun still bears the scars of the terrible fighting that took place there in 1916 (Wikimedia Commons)

Today, WW1 battlefields have mostly reverted to their original state: Belgian and French woods and farmland. Cities, towns, and villages have been rebuilt, although many of the older buildings that survived the war still bear the scars of the conflict.

Picturesque rolling hills, verdant forests, beautiful countryside landscapes, quaint villages, bely the horror and slaughter of the Great War.

However, there are many sections of preserved trenches, such as those at Vimy near the Vimy Ridge Memorial, that stand as monuments to the fighting. They’re great educational tools, giving some insight into the places men of many nations fought, lived, and died.

Many of our Commission cemeteries and memorials sit on former Great War battlefields. For instance, Thiepval sits overlooking the site of the Somme’s former killing fields.

Before the Commission’s founding in 1917, war dead were buried in impromptu graves and cemeteries, sometimes on the battlefield itself. Many of the Commission sites you can see dotted around northern France and Belgium are old battlefield burial grounds built up by the Commission post-war.

The Tyne Cot Memorial is close to the furthest point in Belgium the Allies reached prior to the November 1918 Armistice. In fact, the remains of a German blockhouse can be found within the boundaries of Tyne Cot Cemetery.

If you’re interested in visiting a World War One battlefield, why not take a trip to one of our centres in France or Belgium?

The CWGC Information Centre in Ieper, Belgium, sits close to the site of the Ypres (Menin Gate) Memorial.

Hundreds of thousands of Commonwealth service personnel passed through the city and the gate during the war to head to their positions across the Ypres Salient.

The Ieper Information Centre helps us tell their stories, so their sacrifice is never forgotten.

The CWGC Visitor Centre is our experience hub and visitor attraction in Beaurains, France.

Located in the heart of the battlefields of the Great War, the CWGC Visitor Centre is close to some of the Commission’s most recognisable French war graves and important battlefield locations on the Western Front.

Support our work and help honour the 1.7 million who never returned home

Author acknowledgements

Alec Malloy is a CWGC Digital Content Executive. He has worked at the Commonwealth War Graves Commission since February 2022. During that time, he has written extensively about the World Wars, including major battles, casualty stories, and the Commission's work commemorating 1.7 million war dead worldwide.