08 December 2022

Collapse in the East: The Battle of Hong Kong remembered

In December 1941, the Imperial Japanese pulled off an audacious assault on British-held Hong Kong. This is the story of the Battle of Hong Kong and the personnel who fought there.

Imperial Japanese Army forces storm Hong Kong (Wikimedia Commons)

Empire of the Rising Sun: Prelude to the Battle of Hong Kong

Image: Imperial Japanese Army troops during the Battle of Shanghai (Wikimedia Commons)

Image: Imperial Japanese Army troops during the Battle of Shanghai (Wikimedia Commons)

Since 1931, Imperial Japan had been claiming territories in mainland China.

Japan was going through a major period of aggressive expansion throughout the 1930s. The nation’s imperial ambitions were driven by a hunt for resources, including coal, iron, and oil. Japan is not naturally rich in such items.

Thus, under the guidance of Emperor Hirohito, Japanese military forces began a concerted campaign of conquest across East and Southern Asia.

Starting with the capture of Manchuria in 1931, Imperial Japanese forces began a concerted effort to capture China.

In 1937, Japan launched a full-scale invasion of China. The scale of brutality was enormous. Millions of Chinese civilians suffered at the hands of their new overlords. While Japan would eventually bleed itself dry in China, its initial thrust resulted in thousands of square miles of territory taken and key cities captured.

Shanghai, Nanking, and Beijing were just some of the major territories captured by Imperial Japan between 1937-1940.

In relation to Hong Kong, the Japanese had captured the surrounding Guangzhou (then Canton) region. Essentially, the city was cut off, leaving it a small, British-controlled island in a sea of Japanese-occupied territory.

British Hong Kong

Hong Kong ahead of the invasion, 1941 (© IWM HU 128874)

With the declaration of war on Germany in September 1939, and the war practically on the Home Island’s doorstep, the British Empire was more focussed on Europe during 1940.

Defence studies taken in the Thirties concluded Hong Kong would be extremely hard to hold in the event of a Japanese attack. Defence forces were limited in their scope.

By 1940, only a small number of battalions of British, Indian, and local Hong Kong Volunteer Defence Forces garrisoned Hong Kong, under the command of Major-General Christopher Maltby.

Image: Canadian troops dig in in Hong Kong's rocky mountainous ground (© IWM KF 193)

Image: Canadian troops dig in in Hong Kong's rocky mountainous ground (© IWM KF 193)

It was still an important colony, but Hong Kong had slid down the priority totem pole as war raged across Europe. British Chiefs-of-Staff in London had dubbed Hong Kong an “undesirable military commitment”.

Withdrawing troops would damage Britain’s prestige in the region. It would also doom Hong Kong to terrible violence. Japanese forces had proved particularly violent and cruel in their treatment of Chinese civilians during their occupation of China.

With the Japanese military build-up mounting on the Hong Kong border, Air Chief Marshal Sir Robert Brooke Popham, Commander-in-Chief of Britain’s Far East Command, requested reinforcements. Brooke argued that even a limited number would help the garrison slow down a Japanese assault enough to gain time elsewhere.

C Force, consisting of two just shy of 2,000 Canadian troops from the Winnipeg Grenadiers and Royal Rifles of Canada, was dispatched to reinforce the Hong Kong garrison.

Additionally, Major-General Maltby had overseen efforts to reinforce the 22-mile Gin Drinkers Line of defences on the Kowloon Peninsula in the mid-1930s.

A map of the Gin Drinkers Line (Wikimedia Commons)

Dubbed the “Oriental Maginot Line”, it was hoped this defensive fortification would forestall any Japanese advance. Maltby hoped the Gin Drinkers Line would hold out for at least seven days before forces required evacuation to Hong Kong Island.

However, the Gin Drinkers line was undermanned. Its maximum depth between land and sea was just one mile. It was unlikely to be anything more than a speed bump against the Japanese troops arrayed before it.

Hong King’s air forces were pitifully small too. The Royal Airforce could field three obsolete Vickers Vildebeest bi-plane torpedo bombers. The Fleet Air Arm could contribute a pair of amphibious Supermarine Walruses. The British aircraft would be totally outclassed in the fighting to come.

Hong Kong’s importance was not reflected by its naval component either. Unlike Singapore, Hong Kong did not boast a permanent Royal Navy presence. Only a scant few old destroyers, torpedo boats and smaller craft were left to defend the port city.

Comparatively, Imperial Japanese forces consisted of nearly 30,000 ground troops backed by 47 planes and a much larger naval contingent.

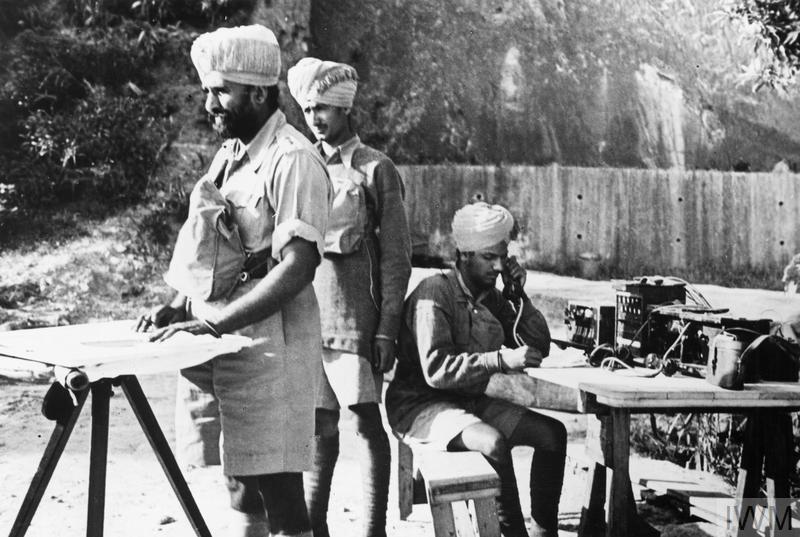

Indian Army troops preparing in Hong Kong ahead of the Japanese attack (© IWM HU 128872)

8th December 1941: Japan strikes against Hong Kong

Image: Japanese troops begin their assault on Hong Kong (© IWM HU 2780)

Image: Japanese troops begin their assault on Hong Kong (© IWM HU 2780)

At 07.30 on December 8th, 1941, Imperial Japan launched its attack on Hong Kong.

The Battle of Hong Kong had begun.

Japanese fighters and bombers first set their sites on the RAF’s meagre air forces stationed at Kai Tak Airport. The Vildebeests were blown away as sleek, modern Japanese warplanes proved just how obsolete the RAF’s outdated planes were.

By noon, Japanese Imperial Army units had crossed the Shenzhen River and pushed back British and Indian army troops to the Gin Drinkers Line. Retreating British forces blew up key bridges and infrastructure to make the Japanese advance as difficult as possible.

At the Gin Drinkers Line, three battalions stood in defence:

- 2nd Battalion, Royal Scots – West

- 2/14th Battalion, Punjab Regiment – Centre

- 5/7th Battalion, Rajput Regiment – East

On December 9th, a Japanese scouting party of the 228th Regiment noticed weak spots in the Gin Drinkers Line. High ground at the Shing Mun Redoubt allowed whoever hold it complete domination of the Line’s western segment.

A sneak attack was launched at 21.00. By 10.00 on the morning of the 10th of December, Japanese forces had captured the high ground, destroyed bunkers and barbed wire, and taken 27 British and Indian POWs.

A two-pronged Japanese Assault then struck the British fortifications. By the 11th, the position was untenable. Major-General Maltby ordered a retreat with the Royal Scots pulling out first. The Rajput Regiment stayed as a rear guard, only withdrawing to Hong Kong Island by 13th November.

Insufficient troops and a complete underestimation of Japan’s strength by British planners resulted in the Gin Drinkers Line collapse.

British troops pulled back from the Kowloon peninsula and off the Chinese mainland.

The next phase of the Battle of Hong Kong would take place in the city proper.

Hong Kong Surrounded

Image: British Commander Major-General Christopher Maltby (Wikimedia Commons)

Image: British Commander Major-General Christopher Maltby (Wikimedia Commons)

Retreating forces had gone “scorched earth” at Kowloon on December 12th. Oil tanks and dockyards were blown up and all merchant naval vessels scuttled. However, a serious tactical mistake was made when small craft, such as junks and sampans, were left undamaged.

Japanese troops simply used them in their assault on Hong Kong.

While the fighting had been raging at the Gin Drinkers Line, a Japanese naval presence had been established to the south of Hong Kong.

Its commander called for Hong Kong’s surrender, threatening bombardment and annihilation by sea and air. Hong Kong Governor Sir Mark Young flatly refused.

Maltby had a few days to prepare his defences.

Many of the men under his command were still reeling from the retreat from the mainland. Other units, like the Canadian troops, had never seen combat before.

Maltby surmised that the Japanese would prioritise an attack via the Lei U Mun Strait connecting Hong Kong and Kowloon Bay, although an amphibious attack by sea was not ruled out. Defences were prepared with this in mind.

The five-day lull in frontline fighting had given time to the Commonwealth forces to withdraw into the city, but the Battle of Hong Kong was about to enter its final phase.

Hong Kong surrenders

British commanders surrender to the Imperial Japanese Army (Wikimedia Commons)

Hong Kong’s fate seemed all but sealed by Christmas Day, 1941.

Major-General Maltby argued to the Defence Council that prolonging the inevitable would result in many unnecessary deaths, particularly to Hong Kong’s civilian population.

The Defence Council was determined to hold out as long as possible. The Imperial Japanese Army was beginning to break through the remaining Commonwealth defensive positions and close in on key locations in Hong Kong’s Stanley district.

At 15.30, Governor Young and Major-General Maltby surrendered in person to the Imperial Japanese commander General Sakai in the Peninsula Hotel.

At Stanley, Brigadier Cedric Wallis was holding fast, having previously been ordered by Maltby to “hold to the last”. Wallis was informed of the British surrender at 20.00, only to refuse, and request a written order of surrender from his superiors before he and his men would give up.

A message came through to Wallis at 02.30 on the morning of 26th December. Wallis and the men of the Royal Rifles of Canada, the Middlesex Regiment, and the Hong Kong Volunteer Defence Force were the last men to surrender during the Battle of Hong Kong.

During the assault, the Japanese Army perpetrated several massacres of Prisoners of War. The worst of these occurred when 47 men of the Royal Artillery, Royal Army Service Corps, and Royal Canadian Army Service Corps were executed at the Ridge in Repulse Bay.

Reprisals against Hong Kong’s civilian population were exceptionally brutal. An estimated 10,000 were killed, while many more were assaulted, tortured, or mutilated.

The Battle of Hong Kong had turned into the Fall of Hong Kong.

Hong Kong remained in Japanese hands until the end of the war.

Casualties of the Fall of Hong Kong

Commonwealth forces suffered between 1,500-2,275 missing or killed during the Battle of Hong Kong. A further 10,000 were taken as Prisoners of War and subject to horrendous treatment throughout the remainder of the war.

Here are a few stories of men who served during the Battle of Hong Kong.

John Robert Osborn VC

Image: John Robert Osbon VC (Wikimedia Commons)

Image: John Robert Osbon VC (Wikimedia Commons)

John Robert Osborn had been living in Canada for 20 years when the English-born 42-year-old joined the Winnipeg Grenadiers.

John had reached the rank of Warrant officer Second Class and A Company Company Sergeant-Major when the Grenadiers headed to Hong Kong.

The Winnipeg Grenadiers were involved in some of hardest fighting during the Hong Kong campaign. Despite having no prior field experience, the men acquitted themselves well and fought bravely against overwhelming odds.

John’s actions on the 19th of December embodied the fearlessness and spirit of determination the Grenadiers showed in the fighting. Crucially, the won John the Victoria Cross.

The citation for John’s VC, as published in the London Gazette, reads:

“At Hong Kong on the morning of 19th December 1941 a Company of the Winnipeg Grenadiers to which Company Sergeant-Major Osborn belonged became divided during an attack on Mount Butler, a hill rising steeply above sea level.

“A part of the Company led by Company Sergeant-Major Osborn captured the hill at the point of the bayonet and held it for three hours when, owing to the superior numbers of the enemy and to fire from an unprotected flank, the position became untenable. Company Sergeant-Major Osborn and a small group covered the withdrawal and when their turn came to fall back, Osborn single-handedly engaged the enemy while the remainder successfully re-joined the Company.

“Company Sergeant-Major Osborn had to run the gauntlet of heavy rifle and machine gun fire. With no consideration for his own safety, he assisted and directed stragglers to the new Company position exposing himself to heavy enemy fire to cover their retirement. Whenever danger threatened, he was there to encourage his men.

“During the afternoon the Company was cut off from the Battalion and completely surrounded by the enemy who were able to approach to within grenade-throwing distance of the slight depression which the Company was holding. Several enemy grenades were thrown which Company Sergeant-

“Major Osborn picked up and threw back. The enemy threw a grenade which landed in a position where it was impossible to pick it up and return it in time. Shouting a warning to his comrades this gallant Warrant Officer threw himself on the grenade which exploded killing him instantly. His self-sacrifice undoubtedly saved the lives of many others.

“Company Sergeant-Major Osborn was an inspiring example to all throughout the defence which he assisted so magnificently in maintaining against an overwhelming enemy force for over eight and a half hours and in his death, he displayed the highest quality of heroism and self-sacrifice.”

John Robert Osborn was the first Canadian recipient of the Victoria Cross during World War Two. His was also the only VC awarded during the Battle of Hong Kong.

John is commemorated by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission on the Sai Wan Memorial.

Brigadier John K. Lawson

Image: Brigadier John K. Lawson (right) confers with Major-General Christopher Maltby during the Battle of Hong Kong (Wikimedia Commons)

Image: Brigadier John K. Lawson (right) confers with Major-General Christopher Maltby during the Battle of Hong Kong (Wikimedia Commons)

Brigadier John K. Lawson was born on 27th December 1886 in Hull, Yorkshire, UK before emigrating to Canada in 1914.

For a while, John worked as a clerk in the Hudson’s Bay Company before enlisting to fight in World War One as part of the Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF).

During his time on the Western Front, John worked his way up from Private to Warrant Officer First Class before finally being commissioned as a Captain within the CEF. John was twice mentioned in dispatches for his battlefield exploits and was awarded the French Croix de Guerre.

John continued his military career upon his return to Canada. In the Interwar Years, John was part of the Permanent Active Militia, holding various positions across Canada. After attending staff college in 1924, John became an officer in the Canadian Military. He was posted to London, England to serve in the War Office in 1930.

During the defence of Hong Kong, Major-General Maltby split his forces into two commands. The idea was to stop the Japanese from cutting the defending forces in half and defeating them piecemeal.

John was placed in command of the West Brigade. Forces under his command included the Winnipeg Grenadiers, Royal Scots, Punjab Regiment and Canadian Signallers.

Alongside his men, John was caught up in fierce fighting as the Japanese sought to control the island.

At 10.00 on the morning of the 19th of December, John found his headquarters at the important Wong Nai Chong Gap mountain pass surrounded. The HQ staff were trapped.

John radioed his commanders to let them know he was “going outside to fight his way out”. He took several of his officers with him and attempted to affect a breakout.

A Japanese machine gun opened up and raked the small Canadian cabal. John was struck and killed instantly.

Upon the discovery of his body, the Imperial Japanese forces that came across John buried him with full military honours in recognition of his bravery. A chaplain was able to retrieve John’s silver identification disc bracelet and kept hold of it for the duration of his time in Japanese internment. The chaplain was able to return John’s bracelet to his wife, Augusta, and sons Arthur and Michael, after the war’s end.

Brigadier John K. Lawson is today buried at Sai Wan War Cemetery.

Mateen Ansari

Image: Captain Mateen Ansari's headstone in Stanley Military Cemetary (Wikimedia Commons)

Image: Captain Mateen Ansari's headstone in Stanley Military Cemetary (Wikimedia Commons)

Over 10,000 Commonwealth troops were captured and thrown into Japanese POW camps when Hong Kong fell.

The treatment of such prisoners is well known as being particularly harsh and cruel. Prisoners were regularly starved, beaten, or tortured for even the most minor infractions. POW’s experience has been recalled in paintings, poetry, literature, and on screen in films like The Bridge on the River Kwai.

Captain Mateen Ansari of the 5th Battalion 7th Rajput Regiment was one of the many thousands of Commonwealth troops taken captive in December 1941.

Already in a precarious situation, Mateen’s ancestry spelt trouble as his captors discovered his relations to one of India’s Princely States.

Upon learning of his high status, the Japanese demanded Mateen renounce his allegiance to the crown, swear fealty to Japan, and ferment discord in the Indian Army prisoners in the various POW camps.

Mateen refused. He was hurled into the now notorious Stanley Prison in early 1942.

Under Japanese rule, Stanley became a terror house, a place of torture and execution. Mateen was starved and beaten during his stay there but he still refused to waver and give in to his captor’s demands.

Mateen was also held in Ma Tau Chung Camp. During his incarceration, Mateen worked hard to counter Japanese efforts to recruit for their collaborationist Indian National Army. He even helped organise escape attempts by other prisoners.

Despite being continually transferred between Stanley Prison, Mateen remained firm in his allegiances and beliefs throughout his ordeal.

Mateen’s stubborn refusal to break incensed the Japanese prison guards. Eventually, Mateen came to the end of his road.

On 29th October 1943, Captain Mateen Ansari was executed alongside more than 30 British, Chinese, and Indian Prisoners in a mass beheading at Stanley.

For his bravery under incarceration, Mateen was posthumously awarded the George Cross in 1946.

Today, Mateen is commemorated in the Stanley Military Cemetery. His courage and fortitude while suffering in some of the worst prisoner conditions of the war remain inspirational, even some 80 years on from his death.

Commemorating the fallen of the Battle of Hong Kong

We commemorate the Commonwealth’s fallen from the battle across multiple sites in Hong Kong.

Stanley Military Cemetery

Stanley Military Cemetery contains nearly 600 World War Two burials, roughly 420 of which are identified. Nearly all casualties suffered by the Hong Kong Volunteer Defence Force are buried at Stanley, alongside Indian, British, and Canadian casualties.

Hong Kong Memorial

Within Stanley Military Cemetery you’ll find the Hong Kong Memorial. Unveiled in 2006, the Memorial commemorates by name Chinese World War casualties who died in both World Wars but have no known grave.

Sai Wan Cemetery

Close to 1,500 World War Two Commonwealth casualties are commemorated at Sai Wan Cemetery. Nearly 450 or so of the burials here are unidentified. Most of those buried at Sai Wan fell during the short but brutal fighting on Hong Kong Island in December 1941.

At the entrance of the cemetery sits the Sai Wan Memorial. This commemorates more than 2,000 Commonwealth service personnel who died in the Battle of Hong Kong or captivity with no known grave.

The Sai Wan Cremation Memorial commemorates around 145 service personnel who were cremated in accordance with their faith.

Learn more stories of the fallen with the Commonwealth War Graves Commission

With our search tools, you can discover more stories of the Commonwealth’s war dead, who they are, and where they are commemorated.

Find War Dead is your solution for discovering casualties from around the world. Search by name, regiment, location, and many more fields, to discover these men and women.

Want to visit one of our sites or want to learn more about their historical context? Use our Find Cemeteries and Memorials tool to learn more about CWGC locations across the globe.