11 November 2024

Everything you need to know about Remembrance Day

Here’s everything you need to know about Remembrance Day and its importance in commemorating the dead of the World Wars.

Remembrance Day

What is Remembrance Day?

Image: Poppy wreaths laid on the steps of a CWGC Stone of Remembrance for Remembrance Day (Unsplash)

Remembrance Day is an important memorial day observed in the United Kingdom and by many other countries across the globe.

It is a day to commemorate the contribution and loss of British and Commonwealth servicemen and women in the World Wars and all worldwide conflicts since.

When is Remembrance Day?

Image: Service members at the Remembrance Day ceremonies at the Cenotaph, London (Sgt P.J. George UK MOD © Crown copyright 2021)

In the UK, Remembrance Day is held every year on the second Sunday of November.

Remembrance Day grew from, and is also closely linked to, Armistice Day.

Armistice Day is November 11. It marks the signing of the First World War-ending Armistice on November 11, 1918.

Armistice Day was originally dedicated to the remembrance of all fallen Commonwealth soldiers of the First World War. The day’s meaning changed following the slaughter of the Second World War.

The modern Remembrance Day is held on the Second Sunday of November each year and commemorates all British and Commonwealth service members who have died in conflicts worldwide since the First World War.

Remembrance Sunday is traditionally when the bulk of remembrance ceremonies, such as the parade past the Cenotaph, will take place in the UK, but events will take place on Armistice Day too.

When was the first Remembrance Day?

Image: Crowd at Buckingham Palace celebrating signing of Armistice. London, 11 November 1918 (© IWM (Q 56642))

Spontaneous celebrations erupted across the United Kingdom when the Armistice was announced in November 1918.

Streets were lined with jubilant citizens celebrating the end of the conflict that had claimed so much from communities nationwide over the last four years.

The first official Armistice Day took place on November 11, 1919.

King George V led national ceremonies at Buckingham Palace including a great banquet while, up and down the country, events were held at local town and village war memorials.

Processions and wreath layings by veterans and civic dignitaries were part of these proceedings and have become integral to remembrance ceremonies.

From then on, Remembrance became an annual tradition.

As touched on above, Remembrance Day was officially moved from November 11 to November’s second Sunday.

The day was first moved during the Second World War when ceremonies were moved to the first Sunday of the month to avoid disruption to war material production.

At the end of World War Two, debate was held over whether to move the ceremonies back to November 11.

Many felt that continuing that practice would put too much focus on the First World War at the expense of the Second.

The Archbishop of Westminster suggested the second Sunday of November be renamed Remembrance Sunday in commemoration of both World Wars.

The Home Office approved and endorsed the change in January 1946 and so Remembrance Sunday was born. The major national Remembrance ceremonies are held on this day each year.

Why is there a two-minute silence on Remembrance Day?

Part of the original Remembrance ceremonies was a two-minute silence held as a mark of respect for those who died or were left behind by the war.

King George V conceived the silence so "the thoughts of everyone may be concentrated on reverent remembrance of the glorious dead".

The two-minute silence has become an integral part of Remembrance Day ceremonies. It is held at 11 o’clock on each Armistice Day and Remembrance Sunday.

11 o’clock was chosen as this was when the Armistice came into effect on the Western Front, bringing a halt to four years of fighting and killing on the battlefields of France and Flanders.

Who is commemorated on Remembrance Day?

Image: Naval personnel at Cenotaph (Sgt James Wise RAF, UK MOD © Crown copyright 2021)

Remembrance Day was originally focused on commemorating the dead of the First World War.

Since the Second World War, Remembrance Sunday commemorates those British and Commonwealth armed forces members killed in all wars and conflicts worldwide.

Commemoration is not restricted to any one military branch.

Personnel from the Army, Navy, Air Force, Merchant Navy and other sections of the Armed Forces are remembered equally on Armistice Day and Remembrance Sunday. You can read more RAF remembrance stories and Royal Navy Remembrance stories in our blog.

How is Remembrance Day marked?

Remembrance and Armistice Day is marked in several ways, such as:

- Two-minute silence – Among the most iconic remembrance ceremonies is the two-minute silence, a period of quiet contemplation on the loss of so many men and women lost to war worldwide

- Poppy wearing – Instantly recognisable red poppies are worn to symbolise peace and loss. Different coloured poppies are available for different aspects of remembrance, such as black poppies commemorating black servicemen and women, white for pacifism, and purple to commemorate fallen animals

- Wreaths – Poppy wreaths are laid at war memorials and on war graves around the world, becoming common sites at CWGC locations every November

- Services – Thanksgiving and remembrance events are held at churches, town halls, temples, mosques, synagogues and war memorials and cemeteries nationwide

- Processions – The sombre procession snaking its way past the Cenotaph in London may be the most famous, but veterans, servicemen, and more figures parade in cities, towns and villages worldwide on Remembrance Sunday

Which countries celebrate Remembrance Day?

Image: A Remembrance Day wreath laying in Nairobi War Cemetery, Kenya (Guerrillas of Tsavo)

Remembrance Day is primarily celebrated in the United Kingdom.

It is also widely marked in the Commonwealth countries of India, New Zealand, Canada, South Africa, and Australia, alongside the other Commonwealth states that sent men and women to serve in the World Wars.

For some nations, Remembrance Day is the chief national day of commemoration, such as in the UK. In others, other memorial days take precedence, such as in Australia and New Zealand where ANZAC Day is the leading day of remembrance.

November 11 is also an important date in the commemoration calendar for non-Commonwealth states.

Armistice Day is a public holiday on November 11 in France and Belgium, for example, complete with gun salutes, two-minute silences, and parades.

Why Are Poppies Worn on Remembrance Day?

Image: The poppy is amongst remembrance's chief pieces of iconography (Donald C Todd © MoD Crown Copyright 2021)

Poppies are one of the most enduring symbols of remembrance.

Each year, they can be easily spotted pinned to the lapels of millions of people across the UK as the nation comes together in shared commemoration of its war dead.

The destruction wrought by the First World War turned once beautiful landscapes in France and Belgium in churning hellscapes of blood, mud, and wire; cratered-scared killing fields where men were cut down in their thousands.

Amidst the bleak carnage, small spots of beauty emerged. In the ground-up earth, small red poppies would flourish, little flashes of beauty amidst the carnage.

Canadian Lieutenant-Colonel and war poet John McRae immortalised the flowers in his iconic remembrance poem In Flanders Field’s first stanza:

In Flanders Fields, the poppies blow

Between the crosses, row on row,

That mark our place; and in the sky

The larks, still bravely singing, fly

Scarce heard amid the guns below

McRae’s prose inspired American campaigner Moina Michael to push for the adoption of the poppy as a symbol of remembrance post-war. She lobbied governments and militaries, amongst other organisations, post-war, to bring attention to her remembrance campaign.

Further inspired by Michael, French Anna Guérin arrived in London in 1921, planning to sell artificial poppies for remembrance purposes.

Guérin met Field Marshal Haig, Commander of the British Expeditionary Force in the Western Front and a major proponent of veterans’ affairs and persuaded the former Great War general to adopt the poppy.

The newly formed Royal British Legion bought 9 million poppies to raise money to support veterans and sold them on November 11, selling out almost immediately.

From then on, the Poppy campaign has taken place every November.

The poppies, whether as real flowers, paper replicas or metal badges, continue to symbolise the loss, sacrifice, and commemoration of all victims of warfare.

Why is remembrance important?

Remembrance is important as it’s a poignant reminder of the sacrifice and loss experienced by people from all walks of life in times of war.

Other reasons why Remembrance Day is important include:

- An opportunity for reflection – The liberties and freedoms we enjoy today came from the sacrifice made by so many from across the Commonwealth

- Honouring the dead – While the Commonwealth War Graves Commission believes in perpetual commemoration, Remembrance Sunday provides a platform for national honouring of our war dead

- Appreciation for peace – Remembrance services allow us to come together to appreciate the peace and freedoms we enjoy in some parts of the world today built on the sacrifice of previous generations

- Communal history – Shared remembrance is an acknowledgement of our shared history and engaging with your local and national history is a key point of commemoration

Want more stories like this delivered directly to your inbox? Sign up for our newsletter for regular updates on the work of Commonwealth War Graves, blogs, event news, and more.

Sign UpMilitary personnel stories for Remembrance Day

See below for a selection of casualties in Commonwealth War Graves care to reflect on this Remembrance Day.

Captain Anthony Frederick Wilding

Image: Captain Anthony Frederick Wilding (public domain)

Image: Captain Anthony Frederick Wilding (public domain)

Born on 31 October 1883 in Christchurch, New Zealand, Anthony Frederick Wilding was one of his era’s tennis superstars.

Winning his first title in 1901, Anthony went on to win 11 Grand Slam titles, including six singles titles and five doubles championships. To date, he remains the only New Zealander to win a Grand Slam title. He also won a bronze medal at the 1912 Stockholm Summer Olympics.

Outside of tennis, Anthony was an accomplished competitive motorcyclist, winning a 1,300km race from Land’s End to John O’Groats in 1908.

In 1902, Anthony travelled to England to take up studies at Trinity College, Cambridge. He graduated in 1905, returning to New Zealand to join his father’s law practice. He qualified as a barrister and solicitor at the Supreme Court of New Zealand.

At the start of the First World War, the popular celebrity tennis player joined the Royal Marines on the advice of Sir Winston Churchill. He was commissioned as a Second Lieutenant.

Anthony was transferred to the Royal Naval Armoured Car Division in Northern France. He was promoted to Lieutenant in March 1915 and by May had been promoted to Captain.

In his last letter dated 8 May 1915, Anthony wrote: "For really the first time in seven and a half months I have a job on hand which is likely to end in gun, I, and the whole outfit being blown to hell. However, if we succeed we will help our infantry no end."

He was killed on 9 May 1915 leading an armoured car unit at Aubers Ridge during the Battle of Neuve-Chapelle when a shell hit the dugout he was sheltering in.

Anthony is buried in Rue-des-Berceaux Military Cemetery.

Nursing Sister Agnes Wightman Wilkie

Image: Nursing Sister Agnes Wilkie (public domain)

Image: Nursing Sister Agnes Wilkie (public domain)

Agnes Wilkie was born in Oak Bluff, Manitoba, Canada, in 1904.

A keen swimmer and skater, Agnes was described as “pleasant, very quiet, kind, and mild” when she began nursing training at Misericordia General Hospital, Winnipeg, in 1924.

Agnes stayed at Misericordia after completing her training where she enjoyed a successful 13-year nursing career.

The warm, gentle nurse continued to public service when the Second World War came calling, enlisting in the Royal Canadian Navy in January 1942.

Agnes was appointed to HMCS Avalon, a large naval base in St John’s, Newfoundland, on the easternmost tip of North America.

The journey to and from the Canadian mainland was a long and potentially dangerous one.

Agnes and her friend Nursing Sister Margaret Brooke were returning to HMCS Avalon on the night of 13 October 1942 when their ship, the SS Caribou, came into the sites of a lurking German U-boat.

Despite travelling in a convoy, tucked amongst other ships, SS Caribou was struck by torpedoes and within five minutes had sunk into freezing waters.

Agnes and Margaret grabbed onto an upturned lifeboat in the dark, trying desperately to stay afloat as frigid waters attempted to pull them beneath the sea.

Eventually, Agnes lost consciousness and let go. Margaret caught her stricken friend and tried to hold on for as long as possible but, before rescue arrived, the sea proved too strong, claiming Agnes.

Margaret was later awarded an MBE for her valiant attempt to save her friend.

Agnes’ body was later reclaimed and buried with full naval honours at Mount Pleasant Cemetery, St John’s, Newfoundland.

Captain John Aidan Liddell VC MC

Image: Captain John Liddell VC MC

Image: Captain John Liddell VC MC

The first of five children to John and Emily Liddell, John was born on 3 August 1888 in Newcastle upon Tyne, England.

John was schooled at Stonyhurst College, Lancashire, where he was an unimpressive student but, upon going up to Balliol College, Oxford, he began to flourish academically.

He took up interests in science, music, and art but John also began to find affinity in machinery, developing a passion in motoring and cars, and later aeroplanes.

Graduating with a zoology degree, John was offered the opportunity to continue his zoological studies on a trip to Krakatoa. Not wishing to be, in his own words, a “slacker”, John turned this down to pursue a military career.

John joined the Officers’ Special Reserve, 3rd Battalion, Princess Louise’s Argyll & Sutherland Highlanders in 1912 and was promoted to Lieutenant in 1914.

Balancing personal interests and military duties, John acquired his pilots’ wings from the Brooklands Aviation School, Surrey, in May 1914.

On the outbreak of the First World War, John was promoted to Captain and travelled with his unit to the Western Front in August 1914. In October 1914, John received the Military Cross for helping prevent an “awkward situation” in an action at Le Laisnil on the French-Belgian border.

At one point, John was in continuous action for 43 days. The stress, combined with the horrendous conditions of the Western Front, took a toll on John’s health. He was invalidated back to England for recovery in January 1915.

Considering his options, John opted to transfer to the Royal Flying Corps in 1915, making his first flight with No.7 Squadron in July.

His second and final mission took place three days later.

On an aerial reconnaissance mission over Belgium, John and his observer/gunner were ambushed by an enemy aircraft.

Raked with machine-gun bullets, both John and his aircraft were damaged in the dogfight, as was his flight partner. John lost consciousness and his plane dropped thousands of feet, its control mechanism severely damaged.

Himself severely wounded and losing blood, John was able to regain control of his aircraft and brought it back to Allied lines.

By the time he had landed, John’s cockpit was crimson with bloody, slick yet sticky to the touch. He had been able to get himself clear of the downed plane and used several pieces of wreckage to create a crude tourniquet for his leg.

Posing with a weak smile for a camera-equipped medical orderly, John was whisked away to a local hospital for medical treatment.

While there, John received the remarkable news that, for his actions on 31 July 1915, he was to be awarded the Victoria Cross, Britain’s highest medal for military valour.

His Victoria Cross citation, as published in the 20 August 1915 edition of the London Gazette, reads:

“When on a flying reconnaissance over Ostend-Bruges-Ghent he was severely wounded (his right thigh being broken), which caused momentary unconsciousness, but by a great effort he recovered partial control after his machine had dropped nearly 3,000 feet, and notwithstanding his collapsed state succeeded, although continually fired at, in completing his course, and brought the aeroplane into our lines— half an hour after he had been wounded.

“The difficulties experienced by this Officer in saving his machine, and the life of his observer, cannot be readily expressed, but as the control wheel and throttle control were smashed, and also one of the under-carriage struts, it would seem incredible that he could have accomplished his task.”

John’s leg had been badly mutilated in the incident and, despite the good news about his decoration, was deteriorating rapidly. It began to show signs of gangrene and John reluctantly agreed to amputation.

Sadly, this was not enough to halt the infection, and John sadly passed away on 31 August 1915, just eight days after his VC was gazetted.

His body was returned to the UK where he is buried at Basingstoke (South View or Old) Cemetery.

Commander Cornelis Stephanus Theodorus Rietbergen

Image: Commander Cornelis Rietbergen (public domain)

Image: Commander Cornelis Rietbergen (public domain)

Cornelis Rietbergen had already experienced the dangers wartime sailing offered in the First World War when the Second broke out in September 1939.

Born in the Netherlands in April 1889, Cornelis had served in the Dutch Merchant Navy in the Great War. While at sea, he had survived the sinking of his vessel after it was sunk by predatory German torpedoes.

Despite being intimately familiar with the risks of serving aboard merchant vessels in wartime, Cornelis continued to serve with the merchant fleet, and by February 1941, was captain of SS Amstelland.

On 18 February, SS Amstelland was sailing as part of a convoy travelling from Falmouth via the Clyde to Buenos Aeries, Argentina.

The convoy came under attack from German aircraft while sailing west of Ireland in the Atlantic Ocean. Amstelland was hit with bombs as the German planes came screaming down and began to take on water.

For the next two days, her crew attempted to pump water out of the stricken vessel but finally Cornelis gave the order to abandon ship.

While attempting to board a lifeboat, the exhausted Cornelis fell into the freezing sea. He endured 25 minutes of sub-zero temperatures before being pulled out. Succumbing to shop, the captain’s body gave out and he pass away, aged 51.

He was awarded the Bronzen Leeuw [Bronze Lion] posthumously on 23 June 1948 Cornelis was buried in Liverpool (Ford Roman Catholic Cemetery) until 1965 when his grave was brought to Mill Hill Cemetery when the Dutch Field of Honour was being created.

Subadar Richhpal Ram VC

Image: Subadar Richhpal Ram VC (public domain)

Image: Subadar Richhpal Ram VC (public domain)

Born on 20 August 1899 in the village of Barda in Haryana, northern India, Ricchpal Ram VC spent over 20 years in the Indian Army.

Ricchpal, who had two sons and a daughter, had first enlisted in 1920, joining 4/6th Rajputana Rifles.

Richhpal was a 41-year-old Subedar when he performed the actions that saw him posthumously awarded the Victoria Cross: the British Empire’s highest award for gallantry.

In February 1941, the Indian Army was engaged alongside its Commonwealth comrades in fighting in Eritrea, East Africa, against Fascist Italian forces.

On 7 February 1941 during the Battle of Keren, Subedar successfully led an attack on the Italian troops facing his unit and repelled six subsequent counterattacks. He ran out of ammunition but was able to successfully bring his company’s wounded back from the combat zone.

Five days later, Subedar went forward with his men again. In the heat of combat, Subedar was wounded terribly, losing his right foot. He continued to encourage his men onward until he succumbed to his injuries.

For this action, Subedar was posthumously awarded the Victoria Cross. His medal citation, published in the 4 July 1941 edition of the London Gazette, gives more details:

"During the assault on enemy positions in front of Keren, Eritrea, on the night of 7-8th February, 1941, Subadar Richpal Ram, who was second-in-command of a leading company, insisted on accompanying the forward platoon and led its attack on the first objective with great dash and gallantry.

"His company commander being then wounded, he assumed command of the company, and led the attack of the remaining two platoons to the final objective. In face of heavy fire, some thirty men with this officer at their head rushed the objective with the bayonet and captured it.

"The party was completely isolated, but under the inspiring leadership of Subadar Richpal Ram, it beat back six enemy counter-attacks between midnight and 0430 hours. By now, ammunition had run out, and this officer extricated his command and fought his way back to his battalion with a handful of survivors through the surrounding enemy.

"Again, in the attack on the same position on 12th February, this officer led the attack of his company. He pressed on fearlessly and determinedly in the face of heavy and accurate fire, and by his personal example inspired his company with his resolute spirit until his right foot was blown off.

"He then suffered further wounds from which he died. While lying wounded he continued to wave his men on, and his final words were 'We'll capture the objective'.

"The heroism, determination and devotion to duty shown by this officer were beyond praise, and provided an inspiration to all who saw him."

Ricchpal was a practising Hindu and was cremated in accordance with his faith. He is commemorated on the Keren Cremation Memorial in Keren, Eritrea.

Support our work to keep their memories alive

As well as caring for war cemeteries and memorials worldwide, we tell the stories of those who fought and died during the World Wars. Help us keep their stories alive to make sure their sacrifices are not forgotten and their stories preserved for evermore.

Support our work and help honour the 1.7 million who never returned home

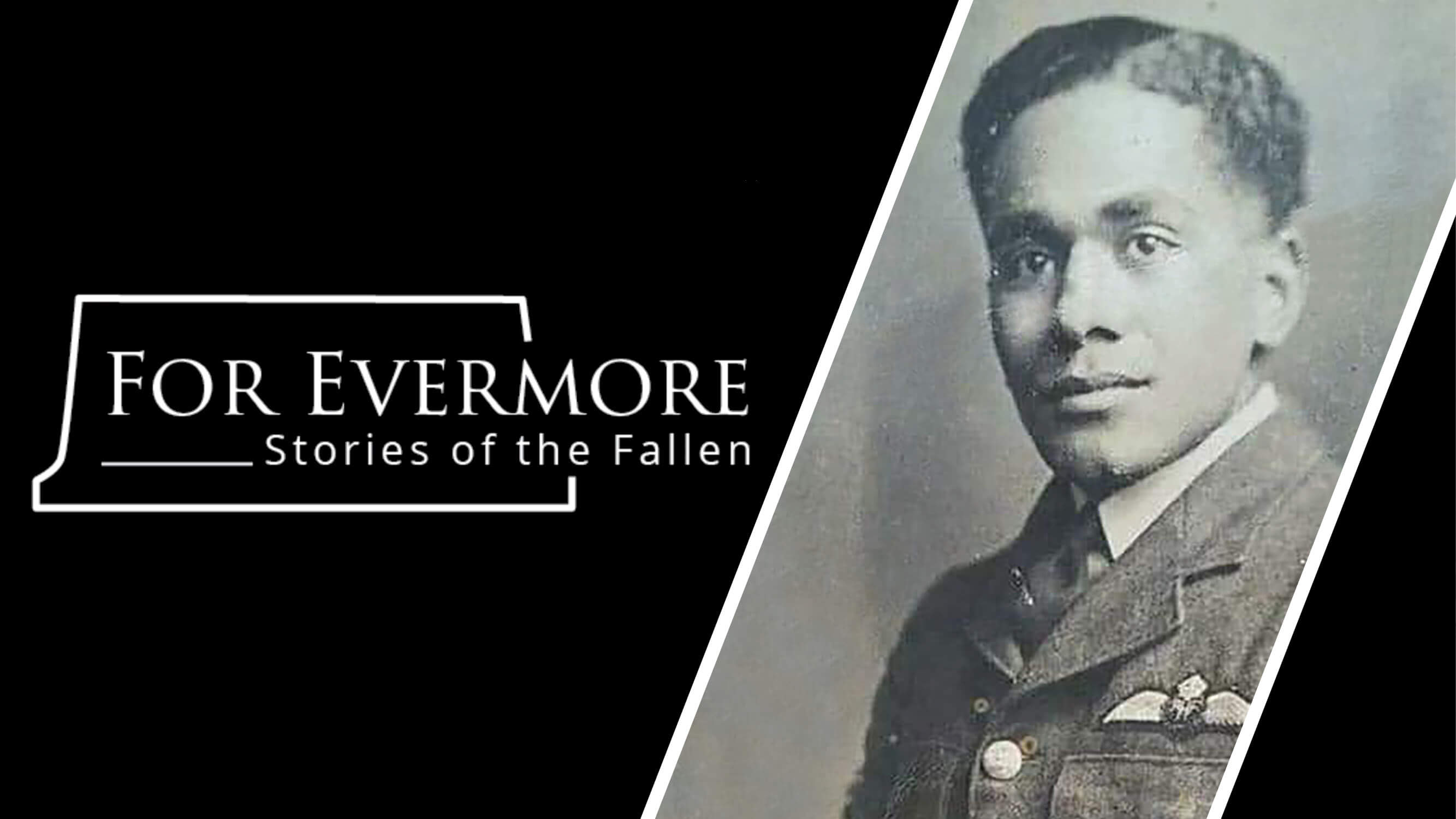

Introducing For Evermore: Stories of the Fallen - the exciting new way to read and share stories of the Commonwealth's war dead. Got a story to share? Upload it and preserve their memory for generations to come.

Share and read storiesAuthor acknowledgements

Alec Malloy is a CWGC Digital Content Executive. He has worked at the Commonwealth War Graves Commission since February 2022. During that time, he has written extensively about the World Wars, including major battles, casualty stories, and the Commission's work commemorating 1.7 million war dead worldwide.