03 February 2025

From For Evermore: Fallen of the Far East

Read some of the incredible stories shared on For Evermore: Stories of the Fallen, our online archive, of those who fell in the final year of the Second World War in the Far East.

War dead of the Far East

Lieutenant Robert Hampton Gray VC DSC

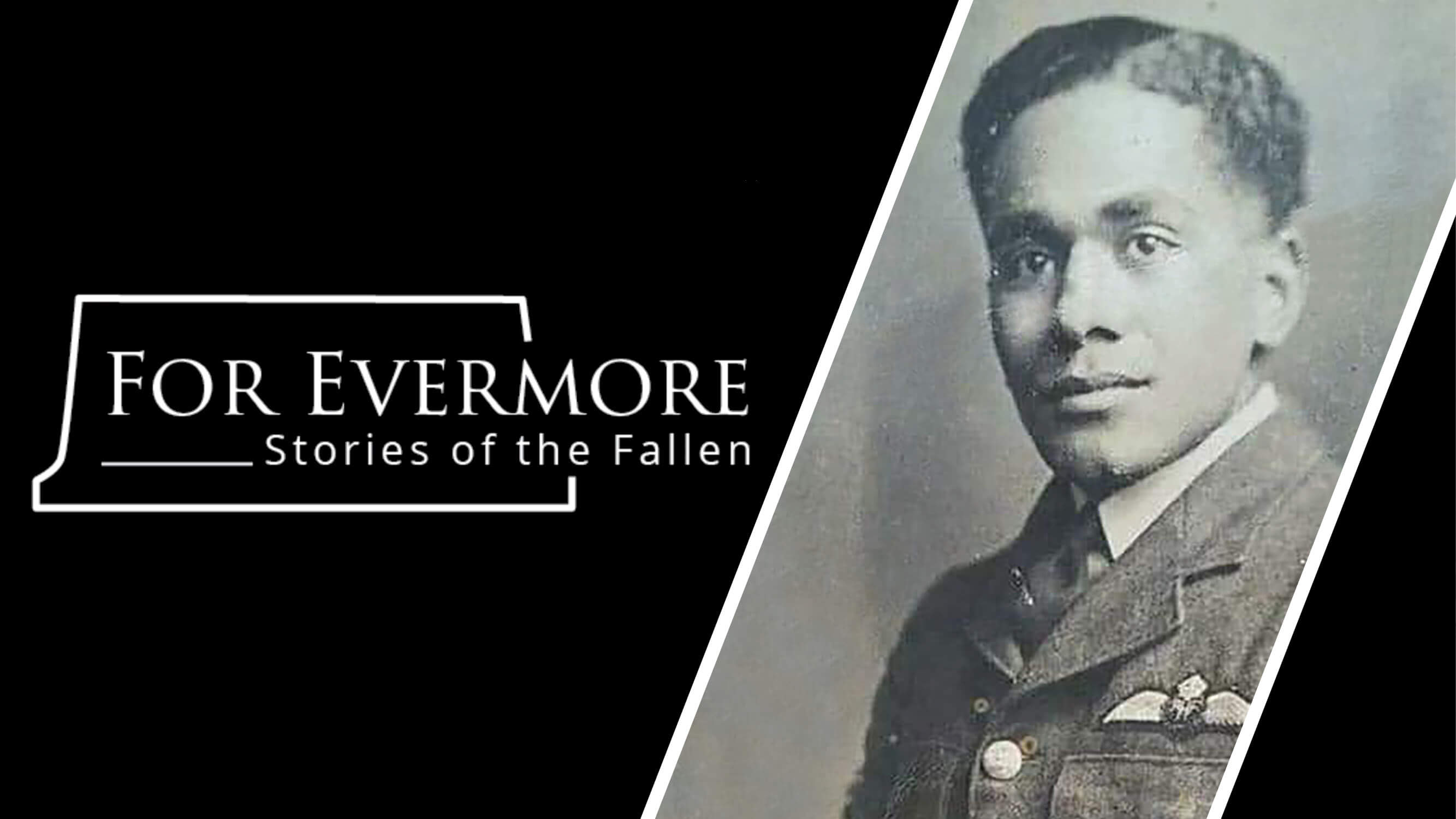

Image: Lieutenant Robert Hampton Gray (Public Domain)

Image: Lieutenant Robert Hampton Gray (Public Domain)

Robert Hampton Gray was born to parents Randolph and Nellie Gray on 2 November 1917 in Trail, British Columbia, Canada. While born in Trail, Robert was raised in Nelson where his father was a jeweller.

Following his education at the Universities of Alberta and British Columbia, Robert pursued a military career, joining the Royal Canadian Naval Volunteer Reserve in 1940.

Robert was first sent to England for training but returned to Canada to complete further training at RCAF Kingston. Upon completing this, he was sent back to the UK where he joined 757 Naval Air Squadron based in Winchester.

Robert was later transferred to Kenya to serve in the East African theatre. At the controls of Hawker Hurricanes, the Canadian naval pilot performed mostly shore-based operations, spending two years in Nairobi.

1944 saw Robert reassigned to 1841 Naval Air Squadron, based on the Illustrious-class aircraft carrier HMS Formidable. Between 24-29 August 1944, Robert took part in the unsuccessful Operation Goodwood raids on the formidable German battleship Tirpitz hiding in the fjords of Norway.

On 29 August 1944, Robert was Mentioned in Dispatches for his part in an attack on three German destroyers. During the air assault, the rudder of Robert’s plane was shot off, but he still managed to survive and nurse his craft back to base.

He was belatedly Mentioned in Despatches again on January 16 1945, for “undaunted courage, skill and determination in carrying our daring attacks on the German battleship Tirpitz”.

HMS Formidable joined the British Pacific Fleet in April 1945 as naval requirements lessened in Europe. Formidable and her carrier aircraft supported the invasion of Okinawa and in July, Robert was involved in strikes on the Japanese mainland.

Robert was decorated with a Distinguished Service Cross for his part in the sinking of a Japanese destroyer on July 28.

On August 9th, 1945, at Onagawa Bay, Robert led an attack on a group of Japanese naval vessels, sinking the Etorofu-class escort ship Amakusa before his plane was hit and crashed into the bay. For this action, he was awarded a posthumous Victoria Cross.

His medal citation reads:

“For great valour in leading an attack on a Japanese destroyer in Onagawa Wan, on 9 August 1945.

“In the face of fire from shore batteries and a heavy concentration of fire from some five warships Lieutenant Gray pressed home his attack, flying very low in order to ensure success, and, although he was hit and his aircraft was in flames, he obtained at least one direct hit, sinking the destroyer.

“Lieutenant Gray has consistently shown a brilliant fighting spirit and most inspiring leadership.”

Robert was one of the last Canadians killed in the Second World War. He was also the war’s final Canadian Victoria Cross.

As Robert's body was never found, he was listed as “Missing in action and presumed dead” and he is commemorated on the Halifax Memorial in Point Pleasant Park, Halifax, Nova Scotia, along with other Canadians who died or were buried at sea during the two World Wars.

Our thanks to Malcolm Peel for sharing Robert’s story.

Captain John Bernard Oakeshott

Image: Captain John Bernard Oakseshott (Courtesy of the Oakeshott and Seccombe families)

Image: Captain John Bernard Oakseshott (Courtesy of the Oakeshott and Seccombe families)

In 1939, John Oakeshott was a 38-year-old married father of two, working as a doctor in Lismore, North South Wales, Australia.

Come wartime, John chose to use his medical training by joining the 10th Australian General Hospital, shopping out to Singapore in 1941. Like tens of thousands of Commonwealth troops, he was captured when the city fell, becoming a prisoner of war.

John was sent to Borneo in 1942 and was transferred to Sandakan in June 1943.

In 1945, John was part of the second group forced on the Sandakan Death Marches. He was one of the last 38 POWs left alive at Ranau by the end of July.

A guard warned one of John’s fellow prisoners that the Japanese intended to kill them. John was offered the chance to join the small band of POWs planning their escape but chose to remain with the sick and dying men. He did, however, give one of the escapees his boots.

John and 14 others were shot by their Japanese guards on 27 August 1945. Tragically, the Japanese government had surrendered 12 days earlier.

Back in Lismore, John’s family had heard nothing of him since a brief Red Cross postcard in late 1942.

Two months after celebrating V-J Day, hoping for John’s return, his wife received a grim telegram informing her of her husband’s death.

Today, John is buried in the Commonwealth War Graves Commission site at Labuan War Cemetery in a grave with four of the men he refused to leave.

Want more stories like this delivered directly to your inbox? Sign up for our newsletter for regular updates on the work of Commonwealth War Graves, blogs, event news, and more.

Sign UpMajor Hugh Paul ‘Grandfather Longlegs’ Seagrim GC DSO MBE

Image: Major Hugh Paul Seagrim (Public domain)

Image: Major Hugh Paul Seagrim (Public domain)

Hugh Paul Seagrim had ambitions to be either a doctor or church missionary in his adult life, but circumstances prevented this. Still, his innate compassion would remain central to Hugh’s character, despite being thrust into the deadly, unforgiving war in the Far East.

Hugh, born on 24 March 1909 in Ashmansworth, Hampshire, England, was the youngest of five sons of Reverend Charles Seagram and his wife Amabel.

He was unable to attended to university after the death of his father in 1927. Putting aside his previous career hopes, Hugh joined his brothers in the military. He attended Military College Sandhurst, joining the 19th Hyderabad Regiment, British Indian Army, upon graduation.

Hugh was seconded to the 20th Burma Rifles with the temporary rank of Major. While in Burma (present-day Myanmar), he became an expert in several local languages, passing his Burmese examination in just five weeks.

Standing at an imposing height of 6’ 4”, he was given the affection nickname “Grandfather Longlegs” by his men.

When Japanese forces invaded Burma, Hugh helped raise guerilla units from the local Karen rebels. With the British retreat from Burma by May 1942, his guerilla force was isolated until October 1943 when agents and radio operators from Force 136 were dropped into Burma and established contact.

He led the Karen guerrillas on sabotage raids against the Japanese, supported by the local population which suffered brutal reprisals. During his service, he was awarded the DSO and MBE.

Gradually his force was whittled away to a point where Hugh surrendered to prevent further reprisals on 15 March 1944.

Hugh attempted to take full blame for the actions of his forces and to spare the Karens who had surrendered with him, but all were sentenced to death and executed on 22 September 1944. Hugh was 35 years old.

In September 1946, he was posthumously awarded the George Cross, the citation in the London Gazette reading:

“Awarded the George Cross for most conspicuous gallantry in carrying out hazardous work in a very brave manner. Major Seagrim was the leader of a party which included two other British and one Karen officer working in the Karen Hills of Burma.

“By the end of 1943 the Japanese had learned of this party who then commenced a campaign of arrests and torture to determine their whereabouts.

“In February 1944 the other two British officers were ambushed and killed but Major Seagrim and the Karen officer escaped. The Japanese then arrested 270 Karens and tortured and killed many of them but still they continued to support Major Seagrim. To end further suffering to the Karens, Seagrim surrendered himself to the Japanese on 15th March 1944.

“He was taken to Rangoon and together with eight others he was sentenced to death. He pleaded that the others were following his orders and as such they should be spared, but they were determined to die with him and were all executed.”

Hugh was buried in a common grave at the Hantawaddy Road Civic Cemetery and was recovered and reburied in the Rangoon War Cemetery, Collective grave 4.A.13-20 on 1 May 1946.

His brother Lieutenant Colonel Derek Anthony Seagrim also fell during the second World War and was awarded the Victoria Cross. Hugh and Derek have the distinction of being the only siblings awarded Britain’s highest awards for gallantry.

Jemadar Parkash Singh VC

Parkash Singh was born in Kashmir on 1 April 1913.

In February 1945, Parkash was serving as a Jemadar, a Commissioned Officer, in the 14th Battalion, 13th Frontier Force. His unit fought against the Imperial Japanese Army at Kanlan Ywathit in Burma, present-day Myanmar.

On 17 February, Parkash commanded a platoon facing the main thrust of a heavy Japanese attack.

The combat was incredibly fierce. Parkash was wounded in both ankles during the fighting and relieved of command. However, his second-in-command, who had taken up the platoon’s leadership, was struck and wounded too.

Parkash crawled back to the front despite his wounds, directing his platoon and encouraging his men onward. He was wounded in both legs again but continued to move from position to position to encourage his men.

Struck a third time, Parkash lay at the front but continued to encourage his men by shouting the famous Dogra war cry, “Jawala Mata Ki Jai! (Victory to Goddess Jawala)”.

The third injury proved to be fatal and Parkash fell, aged 31.

For his incredible courage and lack of concern for his injuries, Parkash was posthumously awarded the Victoria Cross.

His medal citation reads:

“At Kanlan Ywathit, in Burma, on the night of 16th/17th February, 1945, Jemadar Parkash Singh was in command of a platoon of a rifle company occupying a company defended locality. An hour before midnight the Japanese launched a series of fierce attacks, the main weight of which was directed against Jemadar Parkash Singh's platoon.

“Within the first half hour, he was severely wounded and was unable to walk. His company commander ordered him to be relieved, but a short time afterwards his relief was wounded, and he crawled forward and again took command of his platoon sector.

“In turn he fired the platoon's 2-inch mortar, the crew of which had been killed, and the machine-gun belonging to a section all of whom were casualties. At this stage he was once more badly wounded in both legs, but continued to drag himself about by his hands. He re-grouped the remnants of his platoon around him so that they successfully held up a fierce Japanese charge.

“Nearly three hours after the Japanese attacks began, Jemadar Parkash Singh was wounded for the third time in the right leg, but though so weak from loss of blood that he could not move and was obviously dying, he continued to direct and encourage his men, and so inspired the company that the enemy were finally driven out from the position.”

Parkash is today commemorated on the Rangoon Memorial.

Share your stories today on For Evermore

For Evermore: Stories of the Fallen is our online resource for sharing the memories of the Commonwealth’s war dead.

It’s open to the public to share their family histories and the tales of the service people commemorated by Commonwealth War Graves so that we may preserve their legacies beyond just a name on a headstone or a memorial.

If you have a story to tell, we’d love to hear it! Head to For Evermore to upload and share it for all the world to see.

Introducing For Evermore: Stories of the Fallen - the exciting new way to read and share stories of the Commonwealth's war dead. Got a story to share? Upload it and preserve their memory for generations to come.

Share and read stories