23 January 2023

In Flanders Fields: The Life and Death of War Poet John McCrae

In Flanders Fields is one of the ultimate literary expressions of the Great War experience. 105 years after his death, we look at the life and work of the poem’s author John McCrae.

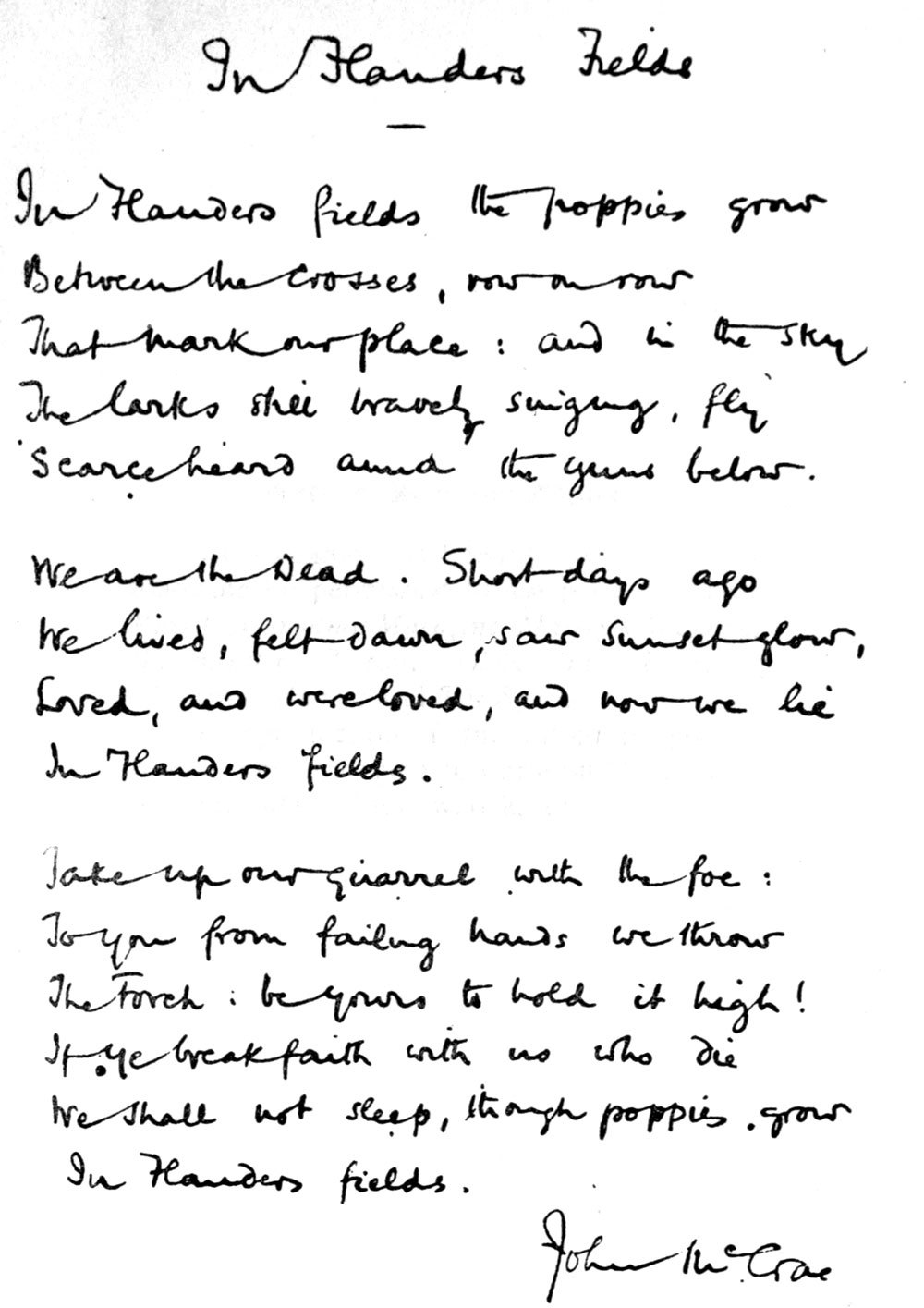

In Flanders Fields

A handwritten version of In Flanders Field, signed by the author (Wikimedia Commons)

An iconic war poem

Think of World War remembrance and what’s the first image that comes to mind? Chances are it’s a single blood-red poppy.

The little flowers, which bloom over the former battlefields of Belgium, are one of the defining symbols of commemoration and remembrance in the UK. But where did it come from? The answer lies In Flanders Fields.

The poem is evocative of the sights John McCrae saw while serving on the Western Front:

In Flanders Fields the poppies grow

Between the crosses, row on row,

That mark our place; and in the sky

The larks, still bravely singing, fly

Scarce heard amid the guns below.

We are the Dead. Short days ago

We live, felt dawn, saw sunset glow,

Loved and were loved, and now we lie

In Flanders Fields.

Take up our quarrel with the foe;

To you from failing hands we throw

The torch; be yours to hold it high.

If ye break faith with us who die

We shall not sleep, though poppies grow

In Flanders Fields

With McCrae’s prose comes imagery that has spread throughout the popular consciousness; the fields of flowers swaying gently in the Flanders breeze; row upon row of crosses standing like a silent sentinel above the bodies of the fallen.

In Flanders Fields was first published anonymously in Punch magazine in London on December 8th, 1915. John McCrae’s journey to getting there is an interesting one.

John McCrae: a war poet’s journey

Image: John McCrae in his military uniform (Wikimedia Commons)

Image: John McCrae in his military uniform (Wikimedia Commons)

John McCrae was born on November 30th, 1872, in a small limestone cottage in Guelph, Ontario, Canada.

The McCraes had military blood. His father was Lieutenant-Colonel David McCrae, a man known for his high principles and strong spirituality. Mother, Janet, and his brother Tom and sister Geills completed McCrae’s family.

The young John had his first literary flurries while a student at the Guelph Collegiate Institute. He also started getting more familiar with military life, joining Highfield Cadet Corps at 14. At 17, John enlisted in the local Militia Fields battery under the watchful eye of his father.

University followed. John studied for three years at the University of Toronto although severe asthma caused McCrae to halt his studies for a year.

Following his graduation, John took up his stethoscope and headed to medical school. While on his way to becoming a doctor, John tutored students to help pay his tuition, two of whom were amongst Ontario’s first female doctors.

While he was learning how to treat patients, heal wounds, and generally become a medical doctor, he was also honing his literary skills. John had 16 poems and several short stories published during his time at medical school across a variety of Canadian publications, including the famous Saturday Night magazine.

John graduated in 1898. His medical career took him from Canada to the United States.

John’s first taste of military service: the war in South Africa

As a dominion of the British Empire, Canada was called upon to serve in the conflict in South Africa that would become the Second Boer War.

John felt the call to serve. He put a pathology fellowship on hold and was subsequently commissioned to lead an artillery battery drawn from men from Guelph.

With D Company, Canadian Field Artillery, John Sailed to South Africa in December 1899. He spent a year there, leaving with mixed feelings about his military experience.

On the hand, John felt the need to serve and fight for his country. The treatment of the sick and the wounded, however, shocked John.

By, 1904, John had been promoted twice, reaching the rank of Captain and finally Major. He resigned from the 1st Brigade of Artillery in 1904. It wouldn’t be until 1914 that John would don a military uniform again.

Canada enters World War One

In the intervening ten years, John McCrae continued to develop his poetry and lead a highly successful medical career.

A lot had changed globally since the end of the Boer War in the early 1900s.

The political situation in Europe had become a twisted web of mutual defence pacts, alliances, and incredible tensions. All it would take would one spark to light the flame.

That spark came in the form of Austro-Hungarian Archduke Franz Ferdinand’s assassination in Sarajevo on the 28th of June. The powder keg that was Europe into a deadly conflagration.

On August 4th, Great Britain entered World War One.

As a Dominion in the British Empire, Canada was obliged to join the growing conflict in Europe. However, it was up to the Canadian government how much the nation contributed to the war effort.

In 1910, then-Canadian Prime Minister Sir Wilfrid Laurier remarked that “when Britain is at war, Canada is at war. There is no distinction.” At the time of Britain’s declaration, the national sentiment was in line with Laurier’s views.

Around 619,000 Canadians enlisted in the Canadian Expeditionary Force by the end of the war. One of these was John McCrae.

Ypres city centre after the devastating Second Battle of Ypres (Wikimedia Commons)

Writing In Flanders Fields

In a letter written to his mother, McCrae described the battle as a "nightmare",

“For seventeen days and seventeen nights none of us have had our clothes off, nor our boots even, except occasionally. In all that time while I was awake, gunfire and rifle fire never ceased for sixty seconds ... And behind it all was the constant background of the sights of the dead, the wounded, the maimed, and a terrible anxiety lest the line should give way.”

During the fighting, Lieutenant Alexis Helmer, a friend of McCrae’s from their days in the Militia, was killed. It’s believed this traumatic experience helped inspire In Flanders Fields.

Image: Lt. Alexis Helmer

Image: Lt. Alexis Helmer

Like his comrades prior to the establishment of full-scale Commonwealth War Graves cemeteries and memorials, Lt. Helmer was buried in a makeshift grave. A simple wooden cross marked his resting space. His grave is now lost and Lt. Helmer is commemorated on the Ypres (Menin Gate) Memorial.

Wild poppies had already begun to pop up on graves across Flanders, including Lt. Helmer’s.

According to the poem’s background, McCrae was spotted scribbling away in a notebook by Sergeant Major Cyril Allinson.

Allinson, who was delivering the 1st Brigade’s post, noted McCrae’s eyes were tracked on Lt. Helmer’s grave while he was writing.

According to legend, McCrae handed Allinson his notebook in which In Flanders Fields was taking form. Allinson was so moved by McCrae’s prose that he immediately committed the poem to memory, describing its vivid imagery as “almost an exact depiction of the scene in front of us both”.

McCrae, apparently unsatisfied with his work, is said to have torn out the page, crumpled it up, and thrown it away. It was then picked up by either Allinson, or Canadian journalist and Major-General Edward Morrison.

Other possible origins claim that McCrae wrote the poem in just 20 minutes after the funeral of Lt. Helmer. Another story suggests McCrae worked on In Flanders Fields in between arrivals of the wounded in his aid station.

Despite his alleged initial dislike for the poem, McCrae was convinced by his peers to submit it for publication.

The poem’s publication

Whatever the truth, it is believed that McCrae worked on the poem for several months before its publication in Punch. Soon he would join the ranks of World War One’s most revered war poets.

Interestingly, McCrae first offered the poem to The Spectator magazine in London, but it was rejected.

As mentioned earlier, In Flanders Fields was at first published anonymously. However, Punch did attribute it to McCrae in its end-of-year index.

Another interesting tidbit is that the word “grow” in the first stanza was originally replaced with “blow” by Punch’s editorial team. This was done with the author’s permission and McCrae would use both words interchangeably when writing copies for family and friends.

Soon after it was revealed that McCrae was In Flanders Fields’s author, he was inundated with messages, telegrams, and letters from around the world.

Soon, the poem was becoming one of the most popular with soldiers and civilians worldwide. It was translated into multiple languages, with McCrae quipping: “It needs only Chinese now, surely”.

Its appeal crossed boundaries.

For soldiers, the poem summed up the realities they faced fighting in the hellscapes of the Western Front. For those on the home front, it helped to bring home and define the cause for which young men and women were giving their lives worldwide.

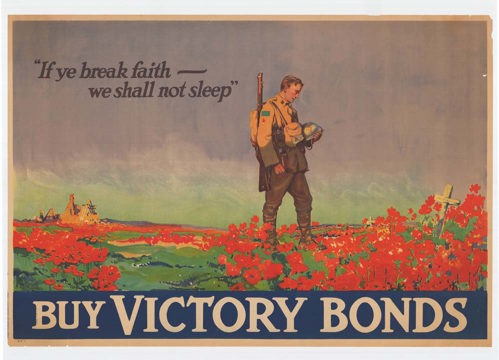

Image: In Flanders Fields was soon used to help drum up support for the war effort, including its use in this Canadian war bonds poster (Wikimedia Commons)

Image: In Flanders Fields was soon used to help drum up support for the war effort, including its use in this Canadian war bonds poster (Wikimedia Commons)

In Flanders Fields also held strong propaganda value. Snippets of the text were used for recruitment campaigns and war bond drives, for example.

It is even believed that its evocative prose helped overcome the conscription crisis rocking Canada during 1917.

A split between French and British Canadians over the issue, with French Canadians opposed to the introduction of conscription.

British Canadians, stirred up by In Flanders Fields, instead voted overwhelmingly for Prime Minister Robert Borden’s Unionist Party and conscription entered law.

McCrae was said to have been pleased with this result.

Death of John McCrae

John McCrae's funeral procession (Wikimedia Commons)

McCrae was transferred away from the Ypres frontline and Canadian big guns soon after writing In Flanders Fields.

No.3 McGill Canadian General Hospital was to be McCrae’s new home. There, he would be Chief of Medical Services, achieving the rank of Lieutenant-Colonel.

Initially, the house was housed in a variety of different-sized Durbar tents sent from India. While massive, the tents were susceptible to the cold wet weather of a Belgian winter.

Eventually, the hospital was moved to a 1,500-bed facility within the ruins of the Jesuit College of Boulogne. Thousands of wounded men would pass through its doors, many for the last time, as the fighting on the Western Front continued.

Despite being proud of his service, McCrae had become to be disillusioned with his lot.

Upon his transfer away from the Artillery, John is said to have told his friend Cyril “Allinson, all the goddamn doctors in the world will not win this bloody war: what we need is more and more fighting men.”

Perhaps feeling guilt at being moved away from the frontlines, McCrae chose to stay in a tent instead of officers’ huts. Many felt the poet’s heart lay with his comrades in the Canadian Artillery, close to the action, instead of treating wounded at the rear.

The once optimistic man with an infectious smile had been replaced with a hard, sterner figure.

He chose to distract himself, as ever, with poetry and writing. He also rode his charger, Bonfire, for long hours through the French countryside. He even took on a canine companion, a spaniel called Bonneau, although sadly this friend would also be claimed by the Great War.

John already had faced respiratory issues as an adolescent with serious asthma. Staying in a tent exacerbated this. Despite being ordered out of his tent and into warmer conditions, John contracted pneumonia and meningitis.

John was transferred to No.14 British Hospital where he died on January 28th, 1918, aged 45.

Image: Grave of Lt. Col John McCrae

Image: Grave of Lt. Col John McCrae

War poet John McCrae was buried in Wimereux Communal Cemetery where he is commemorated to this day.

His funeral was attended by staff, friends, and mourners, including the victor of Vimy Ridge General Sir Arthur Currie.

Bonfire, his faithful horse, led the procession carrying McCrae’s flag-draped coffin to Wimereaux with John’s boots backwards in the stirrups.

A further CWGC monument commemorating John and his most famous work can be found in Essex Farm Cemetery near Ypres.

The legacy of In Flanders’ Field

Image: A Canadian World War Two recruitment poster drawing on the imagery of In Flanders Fields (Wikimedia Commons)

Image: A Canadian World War Two recruitment poster drawing on the imagery of In Flanders Fields (Wikimedia Commons)

In Flanders Fields still carries incredible weight as a piece of poetry.

It remains very popular in Canada and is often recited at Remembrance Day ceremonies both there and in the UK. Extracts of In Flanders Fields have graced World War Two recruitment posters, Canadian postage stamps and even the Canadian ten dollar note.

As the decades have progressed, In Flanders Fields has been re-evaluated. For some, it represents the futility of war and the enormous cost of life conflict brings; for others, it is a reminder of the sacrifice made by young men and women around the world.

The image of red poppies sprouting over the graves of the war dead has become synonymous with remembrance. To this day, the poppy is recognised as an international symbol of remembrance around the world, particularly in the UK and Canada.

The poem’s legacy lives on as a reminder to never forget the slaughter and sacrifice that took place In Flanders Fields over a century ago.

Discover more stories of the Fallen with the Commonwealth War Graves Commission

Our search tools can help you discover the cemeteries and memorials commemorating our casualties like John McCrae.

Use our Find War Dead tool to search for specific casualties by name or by country to learn more about who they are and where they are commemorated.

Looking for a specific location? Use our Find Cemeteries & Memorial search tool to find all our sites. You can search by country, locality, and conflict.