08 April 2024

Legacy of Liberation: Espionage and SOE operations

As well as fighting on air, land, and sea, the Allies fought a more subtle war of intelligence and espionage for the liberation of Europe and beyond.

Here, we tell the story of SOE agents and their clandestine work on the intelligence side of Europe’s liberation.

Espionage and SOE operations during the Second World War

Fifteen female SOE agents commemorated in Europe

Amongst the many hundreds of thousands of Commonwealth casualties of the Second World War commemorated by The Commonwealth War Graves Commission, the names of fifteen women stand out.

Despite nominally holding positions in organisations like the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force or Women’s Transport Service, they were really agents doing underground work for the Special Operations Executive.

Each of these women has an incredible story, mixing incredible courage with devotion to duty in incredibly dangerous conditions. The fact that 15 out of the 39 female agents put into the field by the SOE lost their lives shows just how dangerous being an SOE agent was.

Some were executed in concentration camps; others succumbed to disease: but each lost their lives in the intelligence and espionage war waged by the Allies during the Second World War.

Today, these women are commemorated at various Commonwealth War Graves Commission war cemeteries and memorials in Europe and the Middle East.

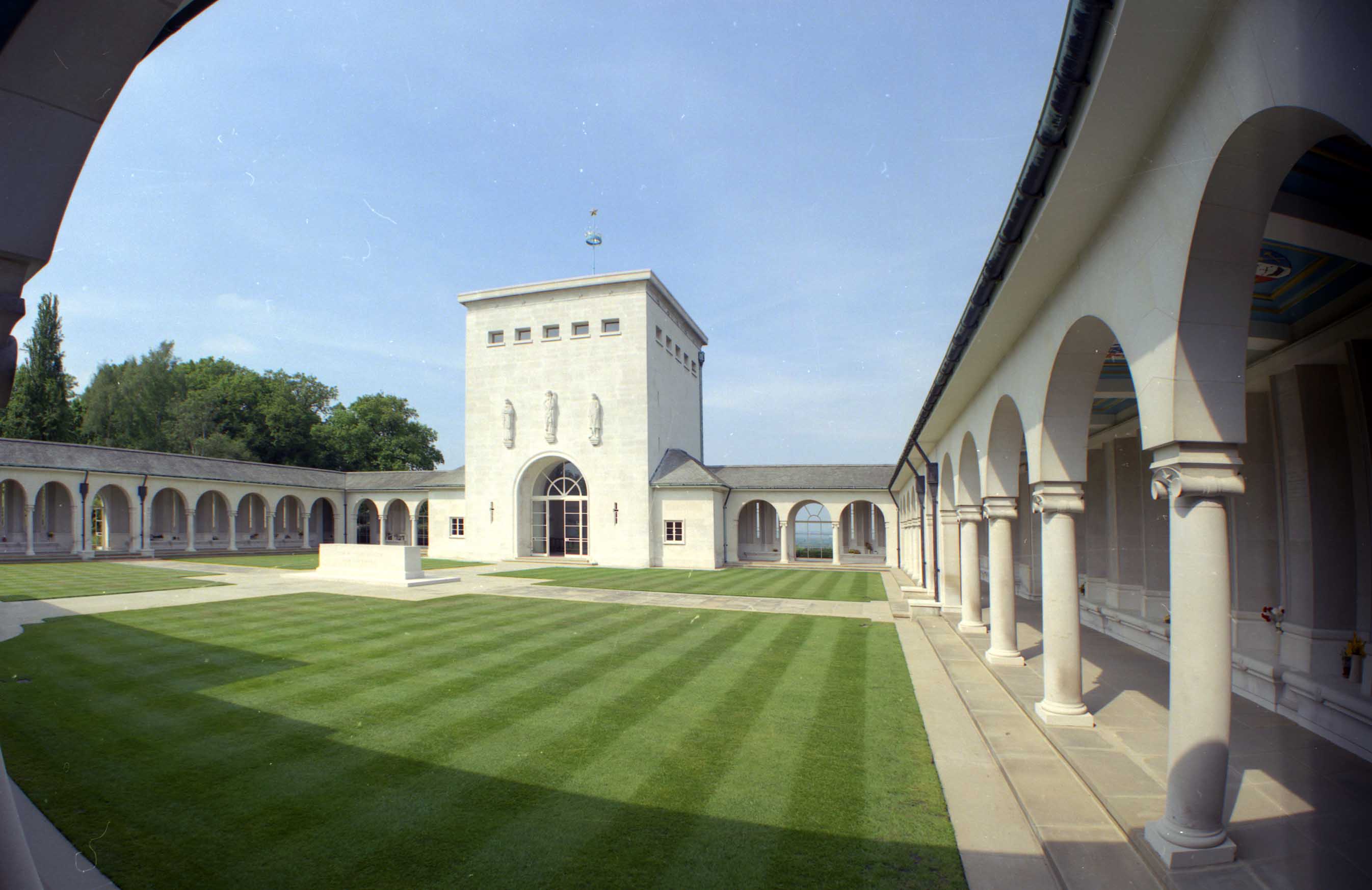

Brookwood 1939-1945 Memorial

Some 3,300 land forces personnel with no known war grave are commemorated on the Brookwood 1939-1945 Memorial.

The circumstances of the deaths of those commemorated by this memorial were such that they could not be appropriately commemorated on specific campaign memorials.

SOE agents’ work sent them deep within enemy territory. Some were captured and executed in concentration camps. Their bodies were not recoverable.

Violette Szabo, Denise Bloch, Elaine Plewman, Madeline Damerment, Vera Leigh, and Andree Borrel were all killed in this manner so are commemorated on the Brookwood 1939-1945 Memorial.

Including these six women, some 33 SOE agents are commemorated by this memorial.

Runnymede Memorial

Female SOE agents from the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force with no known war grave are commemorated on the Runnymede Memorial.

The Runnymede Memorial commemorates by name over 20,000 men and women of the Commonwealth Air Forces lost on operations at home and over Northwest Europe.

Five of the 15 female SOE agents commemorated by Commonwealth War Graves are on the Runnymede Memorial: Noor Inayat Khan, Lilian Rolfe, Yolande Beekman, Diana Rowden, and Cicely Lefort.

Jerusalem Mount Hertzel Cemetery

Hannah Szenes and Chavisa Reik were both part of a small group of Jewish operatives parachuted into occupied Europe on military missions during the Second World War.

Hannah, originally born in Hungary but a resident of Mandatory Palestine at the time of the war, was captured on the Yugoslavia-Hungary border in March 1944. After a period of imprisonment and torture, she was executed by firing squad in October.

Chavisa Reik was dropped into Slovakia in September 1944 to help support the Jewish resistance. At this time, the Slovak National Uprising was underway, aiming to overthrow the region’s Nazi occupiers.

By October 1944, the Germans had begun to violently suppress the rebellion. Chavisa and her fellow operatives and a group of around 40 Jewish resistance fighters retreated to the hills but were captured and executed in the Kremnička Massacre of November 1944.

After the war, both Hannah and Chavisa’s remains were recovered and interred in Jerusalem Mount Hertzel Cemetery.

Violette Szabo

Violette Szabo was one of the female recruits of ‘F’ Section: A SOE unit whose agents were sent to France to work on espionage operations against German forces there.

Violette’s mother was French, so Violette spoke French fluently. She had spent a lot of time there as a child too, making her very familiar with the country: an ideal ‘F’ Section candidate.

After a successful first mission to France in April 1944, Violette was dropped into France on June 7, the day after D-Day.

Three days later Violette was on a courier trip with a resistance leader known as ‘Anastasie’ when they encountered German forces. Their car was stopped at a roadblock and a gun battle took place. Violette was captured but helped ensure that Anastasie was able to escape.

After capture, Violette was brutally interrogated in Fresnes prison in Paris before being deported by train to Germany. During the journey the train was attacked by British aircraft and Violette and another female prisoner took the opportunity - at great personal risk - to take water to the male prisoners.

Violette was executed at Ravensbrück concentration camp in early 1945. Violette Szabo was awarded the George Cross for bravery on the 28th of January 1947.

Noor Inayat Khan

Noor Inayat Khan was born in Moscow in 1914, leaving with her family for Paris and then London after the outbreak of the First World War.

Noor Inayat Khan was born in Moscow in 1914, leaving with her family for Paris and then London after the outbreak of the First World War.

By 1920, the family had returned to Paris.

On the outbreak of the Second World War, Noor and brother Vilayat both wanted to serve. The pair, however, had been raised under a strict code of non-violence.

After escaping France for England with Vilayat, Noor found military service in a non-combat role as a wireless operator with the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force.

As a fluent French-speaking radio operator, Noor attracted the attention of the Special Operations Executive. She was recruited in 1943, becoming one of the first women to receive specialist SOE signals training.

Noor was sent to Frace earlier than expected in June 1943 and made her way to Paris. Unfortunately, the SOE group she was meant to join was about to be broken up by the Gestapo, the NAZI secret police.

This left Noor the only radio operator in Paris. Still, Noor kept up her work in dangerous, difficult conditions, for three and a half months. Eventually, she agreed to return to the UK. Just two days before she was due to leave, she was arrested by the Gestapo.

Imprisoned, enduring torture and interrogation, but refusing to give up any information, Noor was sent to Dachau Concentration Camp where she was killed on 13 September 1944.

What was the Special Operations Executive?

Image: A sabotaged bridge, destroyed via collaboration between local resistance fighters and SOE operatives (© The rights holder (HU 88457))

The Special Operations Executive was formed in July 1940 following the strategic earthquake that was the fall of France.

It was a volunteer force designed to wage a “secret war” of sabotage and subversion behind enemy lines.

Prime Minister Winston Churchill was one of SOE’s chief supporters, famously charging them to “set Europe ablaze”.

Brigadier Collin Gubbins was commander of SOE. He had a long military service record and trained as a Commando. His version of warfare involved sabotage of key infrastructure like bridges, railways, and factories: anything to hurt the Axis war effort.

Gubbins also wanted his agents to support resistance and rebel networks throughout Europe, as we’ve seen from the stories of Hannah Szenes, Chavisa Reik, Violette Szabo, and Noor Inayat Khan.

SOE operatives would engage in clandestine night-time raids, attacking infrastructure targets, as well as coordinating with local resistance groups for sabotage and intelligence gathering.

It was dangerous work. Men and women, working deep in occupied territory, risked capture, torture, and death on SOE missions.

Michael Trotobas

The son of Irish and French parents, Michael Trotobas had all the hallmarks of an SOE ‘F’ Section operative. Handsome, charismatic, quick-thinking, and French-speaking, Michael started his military career with the Middlesex Regiment in 1939.

After leading a platoon at Dunkirk, he was commissioned into the Manchester Regiment before shortly caching the eye of the SOE.

In 1941, under the codename “Sylvestre”, Michael was dropped into Chateauroux, France, for his first mission. After six weeks, his network was broken up by the secret police. Michael and eleven other agents were arrested and placed in Mauzac internment camp.

After less than a year behind bars, Michael was part of a daring camp breakout. Michael and his team evaded an intense manhunt and managed to make their way back to England, via Spain and Portugal.

After less than a year behind bars, Michael was part of a daring camp breakout. Michael and his team evaded an intense manhunt and managed to make their way back to England, via Spain and Portugal.

In November 1942, Michael was back in France with a new brief: sabotage with a priority focus on railways.

Dropping into Lille, armed with a small pistol and 250,000 Francs, Michael used his charisma and cash, spending money freely in bars and gambling dens, to recruit a group of local trusted recruits called the “Farmer Network”. From January to June 1943, the group performed 15-20 derailments a week.

In June 1943, Michael and the Farmer Network, disguised as Gestapo agents, talked their way into the Lille locomotive works and destroyed it. The RAF had made four attempts to destroy the site from the air and had so far failed.

Sceptical officers in London requested photo evidence. By now, the area was teeming with German patrols and officers, on the lookout for the perpetrators.

Posing as an insurance agent, Michael was able to sneak back in, take the requested photos, and eventually mail them to London.

Michael’s wartime exploits ended in November 1943. His location, the back of a Lille café, was given away by an agent under torture. The Gestapo raided the café early one morning and Michael was killed, although he managed to kill and wound two of his attackers.

Michael was recommended for the Victoria Cross but as no senior officers had been around to confirm his actions, he was not awarded one.

Michael is buried in Lille Southern Cemetery.

SOE Radio Operators

SOE radio operators were trained in a technically challenging course before being sent into the field.

They had to be able to send Morse Code, but also understand how to use cyphers and repair their radios.

Acting as the link between London and networks around Europe, radio operators’ work was incredibly important but was equally dangerous. The average life expectancy for volunteer radio operators in the field was just six weeks.

Gestapo officers would interrogate, and torture captured radio operators for their personal codes, with which the Germans could intercept and interpret coded radio messages.

Espionage & D-Day

Image: An RAF aircraft drops supplies for SOE teams & resistance allies in France (NAM. 1985-11-36-276)

"The disruption of enemy rail communications, the harassing of German road moves and the continual and increasing strain placed on German security services throughout occupied Europe… played a very considerable part in our complete and final victory." General Dwight Eisenhower, Supreme Allied Commander, May 1945

The Special Operations Executive played its role alongside other special branches of the military in the run-up to D-Day.

Arms drops were made to local resistance fighters and information was relayed that an invasion was coming, although the actual date was held back until a scant few days before Allied boots hit the Normandy beaches.

Possibly the most important SOE operation of the D-Day story is Operation Jedburgh.

Operation Jedburgh & The Jedburgh Teams

Image: A Jedburgh Team about to board its transport aircraft (Wikimedia Commons)

Operation Jedburgh was a joint operation between the SOE, the US’ Office of Strategic Services and the French Free France Central Bureau of Intelligence and Action (BCRA).

The role of the Jedburghs, or “Jeds” as they became known, was to supplement existing SOE and resistance networks in Europe to help:

- Organise and arm resistance groups

- Arrange supply drops

- Gather intelligence

- Perform Sabotage missions

- Liaise between the Allies and the resistance

Although some Jedburgh teams later operated in the Middle East and the Netherlands, Operation Jedburghs’ primary focus was France.

A Jedburgh team was comprised ideally of three men, including an officer, a French or native speaker, and a radio operator. Sometimes, Jeds were made up of two or four men, depending on the mission.

A mix of nationalities made up the Jedburghs. Brits, Free French, US servicemen, Belgians, Dutch, and Canadians all served in Jed teams.

Jedburgh teams were first dropped into Normandy on the night of 5th June.

Their task was to link up with resistance groups and begin to prepare the ground for the morning’s seaborne invasion. The three-man teams set about delaying German troop movements, often by ingenious means.

For example, the tanks of the 2nd SS Panzer Division were held up by a crafty act of espionage, courtesy of the Jedburghs. A team siphoned the axle oil out of the division’s railcar tank transporters, replacing it with abrasive grease that caused the axles to seize.

For the three months following D-Day, as the Allies fought to force a breakout from Normandy, the Jedburghs continued their work, providing a vital link between Allied high command and resistance fighters throughout France.

GOT An SOE Story? SHARE IT ON FOR EVERMORE

For Evermore: Stories of the Fallen is our online resource for sharing the memories of the Commonwealth’s war dead.

It’s open to the public to share their family histories and the tales of the service people commemorated by Commonwealth War Graves so that we may preserve their legacies beyond just a name on a headstone or a memorial

If you have a story to tell of a casualty we care for who fell in the service of the Special Operations Executive, we’d love to read it! Head to For Evermore to upload and share it for all the world to see.

Visit For Evermore and explore personal stories of service and sacrifice

AUTHOR ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Alec Malloy is a CWGC Digital Content Executive. He has worked at the Commonwealth War Graves Commission since February 2022. During that time, he has written extensively about the World Wars, including major battles, casualty stories, and the Commission's work commemorating 1.7 million war dead worldwide.