17 October 2023

Per Ardua ad Astra: 70 years of the Runnymede Memorial

The Runnymede Memorial celebrates its 70th anniversary this year – but what is the memorial, where is it located, and who does it commemorate? Find out with our latest blog.

Runnymede Air Services Memorial

What is the Runnymede Memorial?

Perched atop a steep escarpment known as Cooper’s Hill, Surrey, overlooking the little boats bobbing slowly along the lazily winding River Thames, sits the Runnymede Air Forces Memorial.

Fittingly, aircraft of all shapes and sizes glide past Runnymede every day. London Heathrow, one of the world’s busiest airports, is a short crow’s flight away.

Runnymede is a site steeped in history. It was here in 1215 that the English Barons and King John inked the storied Magna Carta. The Great Charter is inextricably linked with British ideals of liberty, as is the memorial that stands sentinel over Runnymede to this day.

But why is there a memorial in such a place bursting with historical significance? While the Runnymede Memorial is separate from the events of 1215, it is forever linked to one of the most important events in global history.

Who does the Runnymede Memorial commemorate?

The Runnymede Memorial is dedicated to missing Commonwealth air services men and women of the Second World War.

Image: The Runnymede Memorial commemorates fallen air service personnel of the Second World War (© IWM CH 7208)

Image: The Runnymede Memorial commemorates fallen air service personnel of the Second World War (© IWM CH 7208)

Over 20,000 names are inscribed on its name panels, representing the cost paid by multicultural, multinational Second World War air forces.

These missing personnel were lost on operations from bases in the United Kingdom and north and western Europe but have no known graves. All the Commonwealth nations of the UK, Australia, Canada, India, South Africa, and New Zealand are represented at Runnymede too.

Those operations were not strictly combat missions. Remember, aviation was a little over 30 years old at the outbreak of World War Two. Learning to fly could be just as hazardous as taking on a Messerschmitt in a dog fight during powered flight’s early years.

Casualties can and did occur on routine training missions throughout the war.

A wide variety of different air service branches are represented by those commemorated by Runnymede.

- Bomber Command

- Fighter Command

- Coastal Command

- Transport Auxiliaries

- Training Squadrons

- Maintenance & Ground Crews

Additionally, Runnymede also commemorates those of different nationalities who served within the respective Commonwealth air forces during World War Two.

For example, many from continental Europe whose countries had been overrun by Nazi Germany still wanted to continue the fight and would thus enlist in the Royal Air Force if they could make it to the UK.

Who designed the Runnymede Memorial?

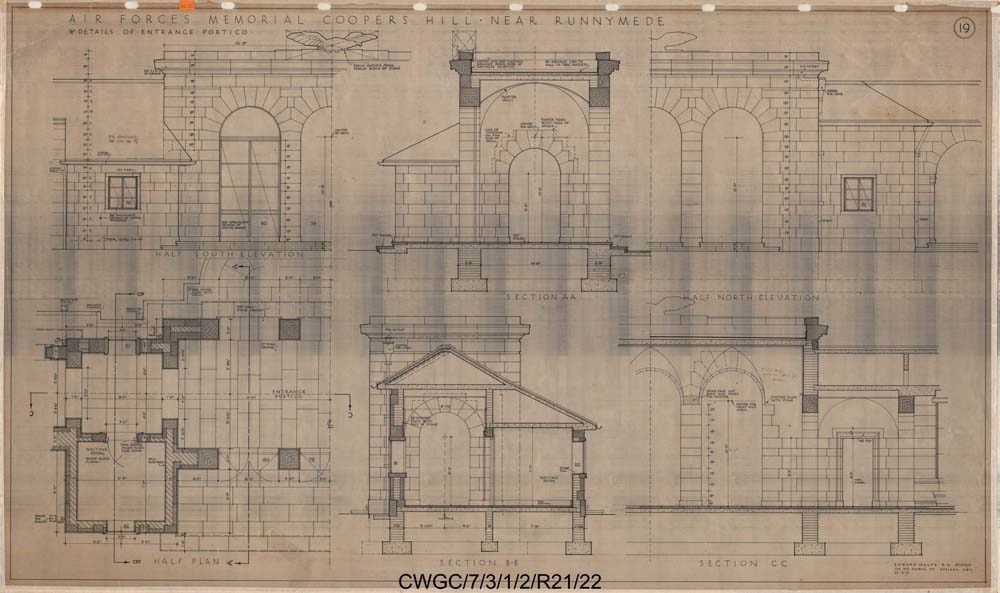

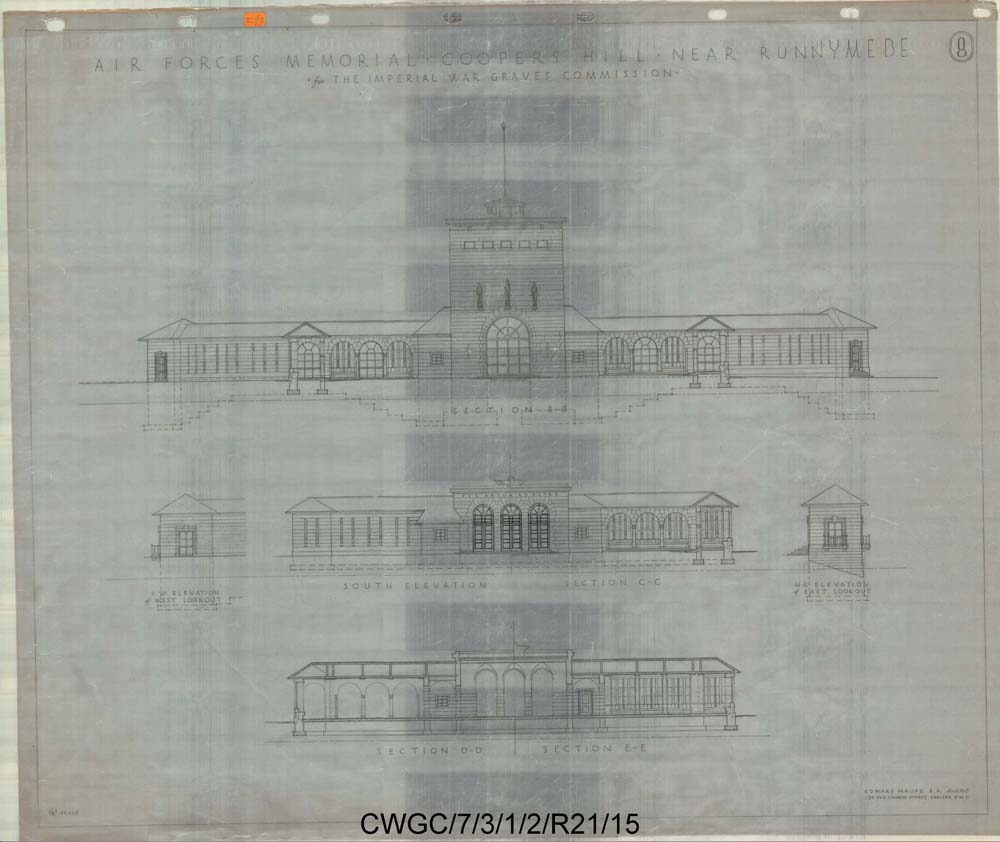

Runnymede was the brainchild of architect Sir Edward Maufe.

Maufe was the then Imperial War Graves Commission’s Principal Architect for the United Kingdom After the Second World War.

For Runnymede, Maufe wanted to create a place of quiet serenity and intimacy, a place where visitors could reflect on the loss of so many men and women in peace.

Each cloister’s panels are arrayed according to year of death. The stone reveals and narrow windows give the impression of partly opened books as if visitors are leafing through a stony book of remembrance.

As with many CWGC war memorials, you can detect the influence of Roman architecture in Runnymede’s design. A series of Romanesque columns, pediments, arches, and other flourishes add to Maufe’s design.

At the memorial’s north end rises the central tower, evoking images of air traffic control towers seen at airfields countrywide during wartime. Climb the staircase to the tower top and be blown away by scenic vistas of Windsor, Heathrow, and distant London.

Decorating the tower’s exterior are three stone figures, representing Justice, Victory, and Courage. A small chapel offers another place to rest and reflect within the tower, with light streaming through the large north-facing windows.

When was the Runnymede Memorial unveiled?

The Runnymede Memorial was unveiled on Saturday 17 October 1953 by Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II.

This was Her Majesty’s first official visit to a CWGC site as reigning monarch and one of her first official duties as Queen of England.

The Queen’s speech reflected on the storied history of Runnymede’s location, as the following extract shows:

“It is very fitting that those who rest in nameless graves should be remembered in this place. For it was in those fields of Runnymede seven centuries ago that our forefathers first planted a seed of liberty which helped spread across the earth the conviction that man should be free and not enslaved.

“And when the lift of this belief was threatened by the iron hand of tyranny, their successors came forward without hesitation to fight and, if it was demanded of them, to die for its salvation.

As only free men can, they knew the value of that for which they fought, and that price was worth paying.”

Some 25,000 or so families and veterans attended the ceremony. Sir Edward Maufe was also on hand to show Her Majesty around the memorial, pointing out its unique design flourishes.

And was also one of the last Commission locations the Queen visited prior to her passing in September 2022, attending the 100th birthday of the Royal Australian Air Force in March 2021.

Casualties commemorated by the Runnymede Memorial

More than 20,000 men and women are commemorated at Runnymede. Here’s a very small selection of casualty stories taken from the memorial.

First Officer Amy V. Johnson

Image: First Officer Amy Johnson (Wikimedia Commons)

Image: First Officer Amy Johnson (Wikimedia Commons)

Amy Johnson was one of the many tens of thousands of women who served in the various women’s air force organisations during the Second World War.

In Amy’s case, she was a pilot with the Air Transport Auxiliary (ATA). The ATA was a vital link in the aerial logistical train.

It was their job to ferry new, repaired, or damaged aircraft, unarmed, from factories and assembly plants to airfields, active squadrons, transatlantic delivery points and sometimes aircraft carriers.

Amy was already a highly experienced pilot prior to the war’s outbreak. More than that, Amy was an aviation pioneer.

In 1930, she became the first woman to fly from Britain to Australia solo. The following year, she and co-pilot Jack Humphries became the first aviators to fly from the UK to Moscow in a single day.

With husband Jack Mollison, Amy would continue to break records, but she was not afraid to answer the call to serve too.

Amy joined the ATA in 1940 and was soon carrying out important transportation missions.

On January 5, 1941, Amy was piloting an Airspeed Oxford training plane between Prestwick, Scotland, and RAF Kidlington in Southern England.

The weather was cold and blustery but began to steadily worsen as Amy made her way south. The conditions were getting too bad for even an experienced pilot like Amy.

Fuel running low, Amy made the weighty decision to bale out, leaping free with her parachute above Herney Bay, near the Thames Estuary.

A nearby convoy of ships spotted the stricken aviator’s parachute as Amy came down. Reports of the incident suggest some of the sailors spotted Amy in the frigid waters, shouting for help.

However, with the snow and sleet peppering the scene, the sailors had difficulty spotting Amy’s whereabouts. The water was bitterly cold too, leaving Amy exposed to sub-zero temperatures.

Lieutenant Commander Walter Fleischer of HMS Hazlemere managed to locate Amy and brought his ship up close. Ropes and lifesavers were hurled overboard but Amy was sucked beneath Hazlemere’s wake and was never seen again.

Later, Amy’s flying bag, logbook, and chequebook were found washed ashore on the shore nearby. Her body was never recovered so Amy is commemorated on the Runnymede Memorial to this day.

Wing Commander Howard Peter “Cowboy” Blatchford

Image: Howard Peter getting out of the cockpit of his aircraft (Wikimedia Commons)

Image: Howard Peter getting out of the cockpit of his aircraft (Wikimedia Commons)

Born in Edmonton, Alberta in February 1912, Howard “Cowboy” Blatchford achieved the first recorded aerial victory by a Canadian in World War Two.

Howard joined the RAF in February 1936, forming a corps of experienced pre-wars pilots the Royal Air Force could draw on in the war’s early days.

In April 1940, Howard joined No. 212 Squadron, a flight reconnaissance unit, though he later transferred to a combat role with No.17 Squadron and later No. 257.

In November 1940, at the controls of a Hawker Hurricane fighter, Howard earned the Distinguished Flying Cross for the following action:

"This officer was the leader of a squadron which destroyed eight and damaged a further five enemy aircraft in one day. In the course of the combat, he rammed and damaged a hostile fighter when his ammunition was expended, and then made two determined head-on feint attacks on enemy fighters, which drove them off. He has shown magnificent leadership and outstanding courage."

Howard became 257 Squadron’s commanding officer in July 1941, and was later promoted to Wing Commander.

Howard would continue to serve with distinction, eventually finding himself in the cockpit of a Supermarine Spitfire as wing leader of RAF Coltishall Wing.

On 3 May 1943, Howard was leading the Coltishall Wing on a bomber escort mission attacking a power station in Amsterdam, The Netherlands, when he was shot down and killed. Howard’s death has been credited to Luftwaffe fighter ace Hans Ehlers.

At the time of his death, Howard’s record was five aircraft claimed shot down, three shared kills, three probables, four damaged, and one shared damaged.

Introducing For Evermore: Stories of the Fallen - the exciting new way to read and share stories of the Commonwealth's war dead. Got a story to share? Upload it here and preserve their memory for generations to come!

Tell Your Story For EvermoreWing Commander John Dering Nettleton VC

Image: John Nettleton (Wikimedia Commons)

Image: John Nettleton (Wikimedia Commons)

Despite earning his Victoria Cross in the skies, John Nettleton actually spent some of his early life at sea.

John was the grandson of Admiral A.T.D. Nettleton and served as a naval cadet in his youth, spending 18 months in the South African Merchant Marine.

In December 1938, however, Nettleton joined the Royal Air Force, commissioned as an officer, joining Bomber Command.

John rose quickly through the ranks, eventually becoming a Squadron Leader with No. 44 Squadron in late 1941.

Around this time, 44 Squadron took delivery of Avro Lancasters: revolutionary new long-range heavy bomber aircraft that would become the workhorse of RAF Bomber Command for the rest of the war.

In April 1942, John and his squadron took part in the Augsburg Raid: a daring daylight attack on MAN U-Boat plants in Augsburg, Germany.

As John’s unit was flying across the French coast at Dieppe, a flight of Luftwaffe fighters appeared, spewing bullets at the Lancasters. Four of the British planes were shot down in the attack. Just John and one other aircraft remained.

Nevertheless, John and the attacking aircraft made it to Augsburg and were able to drop their payloads.

However, a deluge of anti-aircraft fire awaited the British bombers. Both planes were hit as they turned back homeward.

His companion’s Lancaster was shot down in a ball of flame and its crew killed. John’s was damaged too, struggling with a knocked-out engine.

Despite this, John was able to nurse his Lancaster back to the UK, landing at Blackpool after over-flying UK itself, turning back over the Irish Sea.

For his actions during the raid on Augsburg, John was awarded the Victoria Cross: the British Empire’s highest medal for bravery. His medal citation reads:

“Squadron Leader Nettleton was the leader of one of two formations of six Lancaster heavy bombers detailed to deliver a low-level attack in daylight on the diesel engine factory at Augsburg in Southern Germany on April 17th, 1942.

“The enterprise was daring, the target of high military importance.

“To reach it and get back, some 1,000 miles had to be flown over hostile territory. Soon after crossing into enemy territory his formation was engaged by 25 to 30 fighters. A running fight ensued. His rear guns went out of action. One by one the aircraft of his formation were shot down until in the end only his own and one other remained. The fighters were shaken off, but the target was still far distant. There was formidable resistance to be faced.

“With great spirit and almost defenceless, he held his two-remaining aircraft on their perilous course and after a long and arduous flight, mostly at only 50 feet above the ground, he brought them to Augsburg.

“Here anti-aircraft fire of great intensity and accuracy was encountered. The two aircraft came low over the rooftops. Though fired at from point-blank range, they stayed the course to drop their bombs true on the target.

“The second aircraft, hit by flak, burst into flames, and crash-landed. The leading aircraft, though riddled with holes, flew safely back to base, the only one of the six to return.

“Squadron Leader Nettleton, who has successfully undertaken many other hazardous operations, displayed unflinching determination as well as leadership and valour of the highest order.”

Sadly, John did not survive the war. John and his Lancaster were shot down over the Bay of Biscay on route to Italy on the morning of 13 July 1943. John and his crew’s bodies were never recovered.

Discover the stories of the Flying Services' war dead

The stories of the men and women of the flying services are waiting for you to discover them. You can do that with our Find War Dead tool.

You can search by name, regiment, rank and many more metrics to help refine your search.

Want to know where they’re buried or want to visit one of our sites? Use our Find War Memorials and Cemeteries search tool to find a site to suit you.