10 May 2022

The King’s Pilgrimage – the Great War’s full stop

100 years ago, King George V undertook a personal pilgrimage to the newly established Commission cemeteries in France and Belgium. Here's the incredible story of the King's Pilgrimage.

Remembering the King’s Pilgrimage

The King’s Pilgrimage took place between 11-13 May 1922. His journey helped raise the profile of similar pilgrimages and visits to Commonwealth War Graves Commission sites in France and Belgium in the years following World War One. Thousands would make the journey to the continent to pay their respects as they still do to this day.

The world mourns

The world was still processing the trauma of 1914-1918 by 1920.

The world was still processing the trauma of 1914-1918 by 1920.

More than 1.1 million men and women from across the British Empire, including those from the home nations, India, Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and South Africa, were killed during World War One.

By 1920, the first experimental Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC) cemeteries had been established in Europe. Regardless of rank, race, or religion, servicemen and women were laid to rest in our specially designed cemeteries or had their names proudly engraved on memorials.

Because their loved ones’ bodies would lie forever overseas, families and friends flocked in their tens of thousands to the cemeteries and memorials, particularly those on French and Belgian soil. An extraordinary pilgrimage undertaken by ordinary people was underway.

They would soon be joined by royalty.

The King heads to Europe

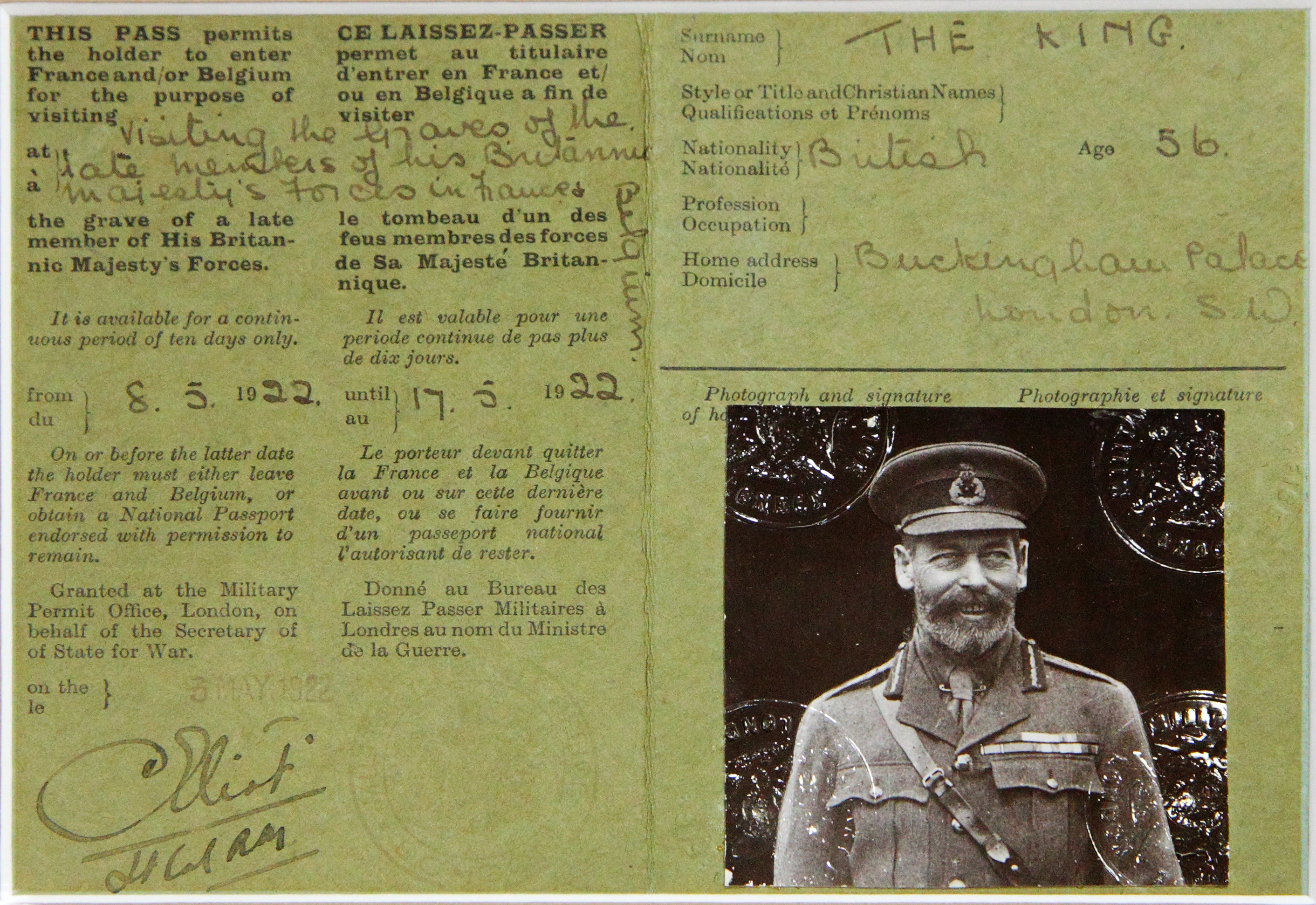

King George V was issued with a passport for his journey to Europe. His surname was given as "The King" while his home address was stated as "Buckingham Palace".

King George V, with a small entourage of military and civilian advisors, including Field Marshal Earl Haig and Commission-founder Sir Fabian Ware, headed to the former battlefields of France and Belgium in May 1922.

King George V, with a small entourage of military and civilian advisors, including Field Marshal Earl Haig and Commission-founder Sir Fabian Ware, headed to the former battlefields of France and Belgium in May 1922.

The King’s goal was to take an understated tour of a number of Commission war cemeteries and memorials to visit those who had died fighting for ‘King and Country’ during the First World War. He would make a special effort to visit graves of those from across the Empire, rather than just focussing on British casualties.

This was to be a low-key affair and the trip was generally free from the usual pomp of a royal visit. The King’s visit would provide an example for others, while also drawing attention to the Commission’s work in commemorating the Empire’s war dead.

The King’s Pilgrimage begins

11th May 1922: the journey's first day

King George V’s journey started in Zeebrugge on the Belgian coast to visit the site of the famous Zeebrugge Raid. Over 200 sailors and 300 marines were lost in a dramatic raid to block or capture the German-held port to hinder Germany’s submarine campaign. Damage caused during the raid could still be seen some four years later when the Royal Party inspected the town.

While in the coastal town, the Royal Party also visited graves in Zeebrugge Churchyard.

Moving on, the Royal Party headed to the Ypres Salient, the site of some of World War One’s most infamous battles.

The Ypres Salient saw action from soldiers from all over the world. It’s home to many CWGC cemeteries as a result including Tyne Cot – then already the largest Commission cemetery in the world. It was here that the King surveyed the former battlefields and suggested the pillboxes should remain as monuments to those who had died.

His Majesty also visited Brandhoek Military Cemetery as well as Ypres Town Cemetery during his pilgrimage’s first day. The visit to Ypres must have been especially poignant for the King as it contained the grave of his cousin Prince Maurice of Battenburg – proof that not even royalty could escape the touch of war.

The King pays his respects to his cousin Prince Maurice of Battenburg in Ypres Town Cemetery.

While in Ypres, The King inspected plans for what would become the iconic Menin Gate with the architect Sir Reginald Blomfield.

12th May 1922: The Royal Party heads to France

The party overnighted and crossed the French border at Vimy.

The Vimy Memorial, commemorating Canada’s war dead and marking the spot of the nation’s great victory at Vimy Ridge, had not been built yet.

The King referred to Vimy as a significant location and messaged the Governor of Canada with words to that effect, but the party didn’t visit any sites there.

The tour then moved along to Notre-Dame-de-Lorette, the French National Cemetery where the Royal Party met with several French dignitaries. Amongst their number was Ferdinand Foch, the Supreme Allied Commander for the final stages of World War One.

The tour then moved along to Notre-Dame-de-Lorette, the French National Cemetery where the Royal Party met with several French dignitaries. Amongst their number was Ferdinand Foch, the Supreme Allied Commander for the final stages of World War One.

Notre-Dame-de-Lorette is not a Commonwealth cemetery, but it is the largest French military cemetery in the world. More than 40,000 French troops are buried there.

A trip through the Somme was next. This region will be forever linked to the British Great War experience. The morning of 1 July 1916, the opening day of the Battle of the Somme, is still the bloodiest day in British military history. Around 57,000 casualties would be sustained that day alone.

The King and his entourage wound their way through the Somme region, taking in visits to Bapaume, Warlencourt and Le Sars cemeteries before reaching Forceville.

Forceville was an early Commission “trial site” – a sort of test case cemetery where the architects experimented with different design features prior to settling on the common elements our sites feature.

13th May 1922: The final day

Representatives from the Dominions were requested to meet with the King at Etaples Military Cemetery on the morning of 13 May 1922. The High Commissioners of Canada, Newfoundland, and New Zealand joined His Majesty at Etaples in shared remembrance, alongside representatives from Australia and South Africa.

Etaples is the largest CWGC cemetery in France and the resting place of more than 11,000 servicemen and women of the Imperial forces.

A particularly touching moment took place at Etaples when the King placed a posy of forget-me-nots on the grave of Royal Army Service Corps Sergeant Matthew after Queen Mary was sent the bouquet by Matthew’s mother.

In keeping with the global focus of the trip, the Royal Party then moved on to Meerut Military Cemetery. Named for Meerut in the Indian State of Uttar Pradesh, this burial ground is the final resting place of some of the soldiers of the British Indian Army who fought on the Western Front. It also contains the burials of Egyptian labourers who took part in the war effort.

A sombre speech at Terlincthun

While the trip had so far avoided with the usual pomp that accompanies royal visits, the King’s Pilgrimage would conclude with a crowning act of homage at Terlincthun Military Cemetery near Boulougne.

Terlincthun sits atop high cliffs overlooking the English Channel. On clear days, it’s even possible to spy the White Cliffs of Dover far off in the distance. On the day of the King’s visit, he would have looked out over the sea to see a fleet of British and French ships waiting to escort him home.

King George led a remembrance ceremony at Terlincthun, joined by Field Marshal Earl Haig, Earl Beatty of the Navy and General de Castelnau of the French Army. A wreath-laying took place, with the King laying one at the cemetery’s Cross of Sacrifice.

The King then gave a sombre yet stirring speech penned by Commission literary advisor Rudyard Kipling. Its words reflected on the cruel nature of warfare and how perhaps the new cemeteries and memorials could act as the strongest arguments for peace:

The King then gave a sombre yet stirring speech penned by Commission literary advisor Rudyard Kipling. Its words reflected on the cruel nature of warfare and how perhaps the new cemeteries and memorials could act as the strongest arguments for peace:

“We can truly say that the whole circuit of the Earth is girdled with the graves of our dead. In the course of my pilgrimage, I have many times asked myself whether there can be more potent advocates of peace upon the Earth through the years to come, than this massed multitude of silent witnesses to the desolation of war.”

While speaking, the King also thanked France for its cooperation in establishing cemeteries where Commonwealth war dead could rest peacefully forever:

"Our fallen lie in the keeping of a tried and generous friend…who, with ready and quick sympathy, has set aside forever the soil in which they sleep, so that we ourselves and our descendants may for all time reverently tend and preserve their resting-places."

Ceremonies concluded with the laying of more wreaths and a speech by General de Castelnau honouring the Allies’ joint contributions to the war and commemoration.

With a final sounding of the Last Post by the Buglers of the Coldstream and Grenadier Guards, the King’s Pilgrimage was over.

Why does the King’s Pilgrimage matter?

For the King, the rows of crosses and gleaming white headstones, standing silent on battlefields where chaos and bloodshed once reigned, each representing a life lost, stood as a stark reminder of the cost of war.

The King’s Pilgrimage sought to highlight the loss the war had brought to communities across the globe. It was symbolic of a network of nations struggling to come to terms with what had happened.

For many, the King’s trip drew a line under the conflict and helped spur on the Empire’s healing process. It’s hard not to be moved by the King’s optimism that our memorials and war graves may help towards establishing lasting peace around the world.

King George’s visit to Commission sites also helped the fledgling organisation gain legitimacy.

With the King’s support, the Commission would gain further acceptance in the eyes of the bereaved. We continue to commemorate the Commonwealth’s war dead to this day.