13 March 2023

Tower Hill Memorial: Who, what, why & when?

How familiar are you with the history of the Tower Hill Memorial? Discover why it was built, who it commemorates, and the background behind this iconic site with the Commonwealth War Graves Commission.

Tower Hill Memorial

Who does the Tower Hill Memorial commemorate?

The Tower Hill Memorial commemorates just over 36,000 Commonwealth casualties of the World Wars.

But unlike other Commonwealth War Graves Commission sites, the men and women commemorated at Tower Hill weren’t strictly military personnel.

Tower Hill instead focuses on those who served in the Merchant Navy and Fishing Fleets during the World Wars but have no known grave.

Their incredible courage and bravery on stormy seas and treacherous waters ensured a steady supply of vital supplies and cargoes reached Allied ports, soldiers, and civilians across both World Wars.

The Commission realised the need to commemorate those who served in mercantile marine missions following the end of World War One. While they may not have been trained to fight, their work was one of the most important parts of the war effort.

Ultimately, the decision was made to give the Merchant Navy its own Commission war memorial. Thus, Tower Hill was raised.

What was the Merchant Navy?

Lifeblood of the Empire

A World War Two British Merchant Navy propaganda poster showing the dangers the men and women had to contend with while at sea.

Did you know that, even before World War One, Great Britain imported over half its food? Nearly half of all cargo vessels and steamships globally flew the Red Ensign of the United Kingdom in 1914.

Even in peacetime, the Merchant Navy was the lifeblood of the British Empire. The men and women that crewed freight ships zipped around the world, carrying foodstuffs and other important goods around the Empire.

As its name suggests, the Merchant Navy refers to the civilian section of the international shipping industry. They came from all over the world, with Indian, Chinese, African, ANZAC, and other nationalities represented in the mercantile fleets’ crews.

Any war, especially two global conflicts, is dependent upon the availability of supplies. Food, ammunition, vehicles, equipment, raw materials, and all the necessary military and civilian materials, require shipping.

While the Royal Navy was a huge force during the World Wars, it alone could not handle the logistical load each conflict presented. Instead, the civilian fleets of the Merchant Navy stepped up and rose to the challenge of keeping the Empire and her armies supplied.

Casualties of the Merchant Navy

Life in the Merchant Navy was hard, dangerous work.

As well as the dangers thrown up by angry seas, frozen arctic waters, tropical storms, and all the risks life on the oceans presents, merchant mariners had to contend with enemy vessels and aircraft too.

Freightliners and cargo ships were targeted from above and below: submarines; bombers; battleships; all these conspired to sink supply ships and destroy Britain and her allies’ trade and war effort.

Every wartime maritime journey offered great danger. Cargo ships were vulnerable to attack, even in home waters. The approaches to Allied ports were often heavily mined and the threat of an aerial attack on docks while at anchor was always a possibility.

Because of these hazards, the merchant marine suffered heavy casualties in personnel and vessels.

Losses of merchant vessels were high from the beginning of World War One. By 1917, the German navy began its policy of “unrestricted submarine warfare”, inflicting massive damage on shipping.

British authorities responded, with the Ministry of Shipping resurrecting the convoy system last seen in the Napoleonic Wars. Warships would escort merchant vessels on treacherous ocean crossings, which lead to a decrease in losses.

Despite these measures, over 3,300 merchant vessels were lost by the end of World War One. 17,000 souls had been lost.

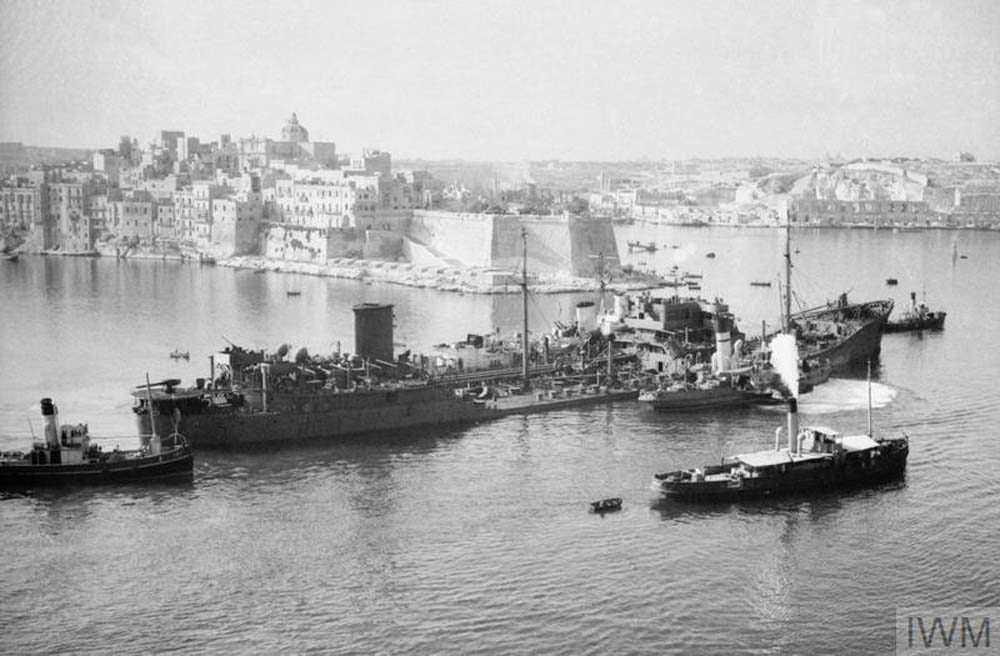

World War Two bought an even greater number of ships passing in and out of friendly ports around the world. At one point during the conflict, over 80% of the world’s shipping was sailing under the Red Ensign.

Once more, sailing bought incredible dangers. German U-boat wolf packs lurked beneath the waves of the Atlantic Ocean, Mediterranean, and arctic waters. Japanese vessels waited in the Pacific and Asian seas.

Losses were again high, peaking in 1942. Millions of tons of cargo was sunk. Thousands of ships were lost. Tens of thousands of men and women were killed.

The Atlantic was a key U-boat hunting ground but convoys heading to Russia and the North Cape, or supplying Malta and the Mediterranean, were particularly vulnerable too.

By the end of World War Two, over 4,750 ships had been sunk or lost at a cost of 32,000 lives.

Those merchant seamen and women who died during the World Wars with no known grave are the people commemorated at Tower Hill.

The range of ages of those who served in the Merchant Navy was huge. Some fell in their fifties and sixties, such as 59-year-old Lilly Ann Green. Lilly went down the SS Andalucía Star in 1942. She was posthumously awarded the King’s Commendation for Bravery for her conduct during her ship’s sinking.

Others were still in their teens when they died.

Donald Owen Clarke GC

Image: Donald Clarke was posthumously awarded the George Cross for his extreme courage in ultimately fatal conditions (Wikimedia Commons)

Image: Donald Clarke was posthumously awarded the George Cross for his extreme courage in ultimately fatal conditions (Wikimedia Commons)

Donald Clarke’s experience showed the courage and commitment of Merchant Navy crews in wartime.

Donald was serving aboard the oil tanker SS San Emiliano as an Apprentice when his ship was torpedoed off the coast of Trinidad on 8th August 1942.

With San Emiliano engulfed in flame, the order was given to abandon ship. Donald, like many of his shipmates, was horrifically burned during the attack.

Donald still managed to guide several wounded crewmembers to a lifeboat while the tanker burned. Donald did all this, despite being terribly wounded himself. Donald’s boat was the only lifeboat to survive the San Emiliano’s sinking.

Donald rowed for two hours to get clear of San Emiliano. His hands were so terribly burned they had to be cut away from the oars as his flesh had fused with the wood. Donald was laid on the bottom of the boat while they awaited rescue but continued to sing songs to keep his crewmate’s spirits up.

Eventually, Donald succumbed to his wounds on 9th August 1942. He was posthumously awarded the George Cross for his selflessness in saving several crewmates at the cost of his own life.

Designing the Tower Hill Memorial

A naval memorial in London

So, what is a monument to men and women who sailed oceans and seas all over the world doing in the UK’s largest city?

At its peak, London was one of the busiest port cities in the Empire. Millions of tons of cargo flowed through its docks, warehouses, and storage yards. It was an important wartime port too.

The Tower Hill Memorial sits just up from the River Thames, just behind the imposing Tower of London. From the site, you can see the slate grey waters of the Thames as it winds its way to the sea.

Hundreds of vessels of all shapes and sizes would have sailed along here during wartime on their way to where their cargo was needed most.

The eventual site for the Tower Hill Memorial sits within the gardens of Trinity House. Trinity House itself is a charity devoted to safeguarding shipping and seafarers, an incredibly fitting location for a naval memorial.

Sir Edwin Lutyens

Image: Sir Edwin Lutyens

Image: Sir Edwin Lutyens

Sir Edwin Lutyens was one of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission’s first principal architects. His designs helped set the visual trademarks, aesthetics, and flourishes that make our cemeteries and memorials visually unique.

As well as Tower Hill, Lutyens’ created several of our most iconic memorials, including the Delhi Memorial (India Gate), India, and the Arras Memorial in France. Lutyens was also the mind behind the Cross of Sacrifice and Stone of Remembrance, two of our most powerful symbols of remembrance and commemoration.

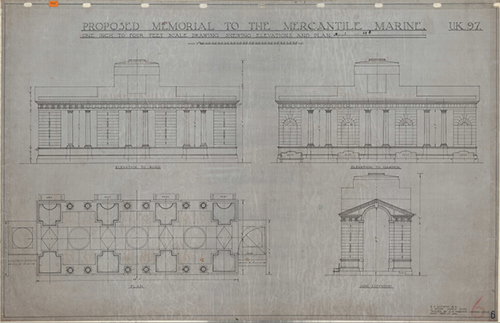

The final form of the Tower Hill Memorial consists of eight stone piers propping up a vaulted Portland stone roof. In between each gap left by the piers sits two columns. A central corridor has been formed by the piers and roof, on which the names of the 12,000 or so First World War casualties can be read.

Additional sculpture was supplied by Sir William Reid Dick.

The Memorial as it stands today is not Lutyens’ original idea. The architects’ first proposal for a mercantile marine monument was a stepped, Portland and granite stone to be built on London’s Thames Embankment.

Lutyens’ original idea ran into barriers put up by the Royal Fine Art Commission (RFAC). The RFAC suggested the memorial would be better placed further downriver in the heart of London’s historic port and docklands.

While Lutyens was not a fan of the RFAC’s proposal, he set to work designing the Tower Hill Memorial as we see it today.

Lutyens's architectural plans for the Tower Hill Memorial

Unveiling the Tower Hill Memorial

Her Majesty Queen Mary unveiled the Tower Hill Memorial on 12th December 1928.

A large number of families, mercantile veterans, and shipping industry representatives attended the unveiling, packing out Trinity House gardens.

During the ceremony, three widows of merchant seamen were presented to the Queen.

If those present at the unveiling had hoped to see the back of such a terrible conflict, they were sadly mistaken. The Merchant Navy would once again be called into action to supply the world during World War Two.

Tower Hill Expands

As mentioned earlier, over 32,000 merchant and fishing industry personnel were killed during World War Two. The almost 24,000 commemorated at Tower Hill have no known grave but the sea.

To accommodate the multitude of new names, Tower Hill was expanded.

Sir Edward Maufe designed the 1939-1945 section of Tower Hill. Maufe chose a sunken garden to house the new bronze name panels.

Explaining his reasoning, Maufe said: “25,000 names have to be recorded: in order to avoid high walls, a sunken garden has been formed with walls of minimum height and length on which to record the names. The whole layout is centred on, and leads up to, the 1914-18 War Memorial.”

Fresh sculpture was added to the Memorial during its World War Two expansion phase. Designed by Charles Wheeler, these aesthetic additions were maritime-themed, including seven allegorical figures representing the Seven Seas.

Two sailors’ sculptures stand either end of the sunken memorial wall. To avoid any overt indication of rank, naval service, and stature, each of the sailors has been sculpted wearing outdoor clothes.

One of the Commission’s central tenants is all are equal in death, which these rankless sculptures are emblematic of.

Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II unveiled the Tower Hill Memorial’s World War Two extension on the 5th of November 1955. Once more, thousands of relatives and veterans were in attendance. 150 mothers and widows made the trip from Denmark to attend.

Visiting the Tower Hill Memorial

The Tower Hill Memorial sits within Trinity House gardens.

The closest Underground station to the memorial is Tower Hill.

Otherwise, it can be found along Byward Street, just behind the Tower of London, across the Thames from Tower Bridge.

The Memorial is open from 08.00 each morning. Trinity House Gardens close each day at dusk.

Tower Hill Memorial in London

Learn more about our Tower Hill casualties with our search tools

Our search tools can help you uncover more stories of those commemorated by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission.

Use our Find War Dead tool to search for specific casualties by name, where they served, which branch of the military they served in, and more parameters.

Looking for a specific location? Use our Find Cemeteries & Memorial search tool to find all our sites. You can search by country, locality, and conflict.