31 January 2023

Tragedy at Sea: The “Battle” of May Island

105 years ago, a deadly naval accident took place off the coast of Scotland. The result? Over 100 British naval personnel dead. This is the strange story of the “Battle” of May Island.

The "Battle" of May Island

Where is May Island?

Image: The rugged Island of May sits off the coast of Scotland in the Firth of Forth. In January 1918, it was the site of a tragic naval disaster (Wikimedia Commons)

The Isle of May sits around five miles off the coast of Scotland at the end of the Firth of Fife.

It has no permanent inhabitants, save the flocks of seabirds that flitter amongst the rocks and play in the sea spray. Two lighthouses break up the island's craggy landscape.

The Isle of May is now a nature reserve. Keen-eyed ornithologists travel there to capture a glimpse of the puffins, the gulls, and the rarer seabirds that call the island home.

Apart from its natural wonders, the island has a connection to the Royal Navy.

During World War Two, six ASDIC were placed along the seabed nearby to detect enemy vessels and submarines heading for the Forth. Their control centre was located on the Island of May.

But our tragic tale takes place on a late January evening in 1918 as World War One enters its critical final year.

Operation E.C.1

Image: The Royal Navy Grand Fleet at anchor in the Forth of Fife (© IWM Q 20633)

Image: The Royal Navy Grand Fleet at anchor in the Forth of Fife (© IWM Q 20633)

January 31st, 1918. A flotilla of 40 Royal Navy vessels had just left the naval base at Rosyth in the Firth of Forth.

They were due to join elements of the Grand Fleet at Scapa Flow near Orkney in the North Sea for a mass night training exercise called Operation E.C.1.

Amidst the convoy heading for northern waters was the 5th Battle Squadron, comprised of three battleships with destroyer escorts, the 2nd Battlecruiser Squadron with four battlecruisers and destroyers, and two flotillas of K Class submarines.

K Class submarines: the “Kalamity Class”

The K Class has gained notoriety amongst submarine and naval enthusiasts since the end of the Great War.

Originally conceived in 1915, the K Class was meant to be a submarine that could keep up with the Grand Fleet. These were relatively speedy vessels, capable of achieving a speed of 24 knots thanks to their steam turbine propulsion system.

Image: K6 out at sea. K Class boats soon gained a notorious reputation thanks to numerous design flaws (© IWM Q 69714)

This speed came with a catch. 24 knots was only achievable on the surface. For undersea travel, the K Class used electric batteries and an emergency diesel engine.

While this system allowed the K Class flexibility, it greatly increased the weight and the bulk.

K Class submarines were considered large for their time, stretching 103 metres from bow to stern. They were unwieldly vessels for even experienced submariners to handle.

They were also had extra holes - something less than ideal for submersible vessels. The steam turbines required two funnels. Because these would need to be closed before a K Class could head beneath the waves, it meant the submarines had a diving speed five times slower than their German counterparts.

Their safe diving depth, 81 metres, was also shorter than the total length of a K Class submarine, adding to crews’ consternation.

Conditions aboard were cramped, hot, and humid. Morale was typically low amidst crewmen, all of whom were volunteers.

So, why “Kalamity Class”? Well, the K-Class was involved in a couple of high-profile accidents ahead of Operation E.C.1.

K13 sank on January 19th 1917 during sea trials. An intake failed to close, flooding the engine. She was eventually salvaged and relaunched as K22 in March 1917.

Submarines K1 and K4 collided with one another off the Danish coast on 18th November 1917. K1 was intentionally scuttled to avoid capture. K4’s fate would be sealed during Operation E.C.1.

Such was their reputation that sailors serving aboard K Class subs referred to themselves as the “Suicide Club” with typical black British humour.

The 12th & 13th Submarine Flotillas

Nine K Class vessels were attached to Operation E.C.1, split into two flotillas consisting of 4 and 5 submarines respectively.

The 12th Submarine Flotilla was led by Captain Charles Little abord the battlecruiser HMS Fearless. Captain Little had been placed in charge of the Grand Fleet’s submarine flotilla in 1916 and would hold that position until the end of World War One.

Under his command in the 12th Submarine Flotilla were K3, K4, K6, and K7.

Joining them in the 13th Submarine Flotilla were subs K11, K12, K14, K17, and K22, led by Commander Ernest William Leir aboard the destroyer HMS Ithuriel.

The convoy sets out

With the ships and vessels assembled, the convoy and its submarine flotillas left Rosyth at 6.30pm on the evening of January 31st.

Captain Leir and Ithuriel followed on from the lead ship, HMS Courageous, with the 13th Submarine Flotilla in tow. Several miles behind the leading ships, HMAS Australia, HMS New Zealand, Indomitable, and Inflexible followed.

Captain Little and the 12th Submarine Flotilla came next, with three battleships and a destroyer screen forming the convoy’s vanguard.

All the ships, at this point travelling in a single line, were ordered to sail 370 metres astern of each other under blackout conditions.

A German U-boat was suspected to be operating in the area, so lighting was at a minimum with blackout shields raised. All each ship had to indicate its location was a small blue astern light.

Seas were calm. The sky was clear, although the moon had not yet risen. The convoy was approaching the Isle of May. Soon, it would be able to head out to clear waters and reach its rendezvous point.

Sadly, some vessels would never make it to Scapa Flow.

Collision off May Island

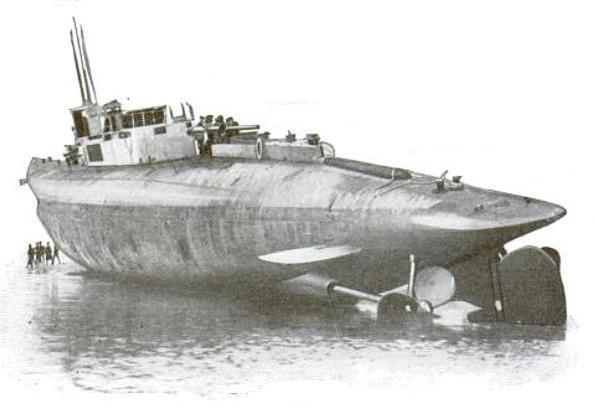

Image: K4, seen run aground here in a previous incident, was one of the unlucky submarines caught up in the May Island disaster (Wikimedia Commons)

7.30 pm.

With the convoy heading for open seas, the leading elements increased their cruising speed.

HMS Courageous passed May Island just as seaborne mist began to sink in. Visibility was soon reduced.

Just as Courageous was making its headway, with the submarines of the 13th Flotilla close behind, several lights were suddenly spotted ahead of the subs’ path.

Eight armed trawlers, small boats equipped with guns during wartime, were in the Firth near May Island. The trawlers were likely sweeping the area for sea mines but had been unaware the Grand Fleet was passing by that night.

Two of the trawlers appeared suddenly directly in front of K14. Its Commander, Thomas Harbottle, frantically changed course.

The minesweepers were dodged but the sudden change in correction by the unwieldy K14 meant it was rammed by flotilla mate K22 at 7.18 pm.

K14’s bow was smashed by her fellow submarine and subsequently severed. Her forward mess deck was breached. Two crewmen were killed instantly.

The two vessels took 15 minutes to untangle themselves. The collision had left both submarines vulnerable. K22 was suffering with two forward compartments flooded. K14 could sink any minute.

Miraculously, both boats were still watertight after 25 minutes. In that time, the men aboard each vessel were frantically signalling on their radios, their Morse-code Aldis lamps, and shooting flares into the night sky.

Despite its crew’s best efforts to warn the approaching Grand Fleet ships, K22 was struck again, this time by HMS Inflexible. Somehow, it still didn’t sink and signalled in coded messages to Ithuriel it could possibly make it back to port. K14, it warned, could go under.

HMS Ithuriel managed to turn back and rescue many stricken submariners in the cold Firth waters. She had to take several drastic evasive maneuverers and course changes to dodge the incoming outbound ships.

The rest of the boats of the 13th Flotilla, including submarines K11, K12, and K17, followed Ithuriel as it escorted the damaged K22 and K14 back to Rosyth.

The 12th Submarine Flotilla arrives with tragic consequences

Image: The massive damage caused to HMS Fearless (Wikimedia Commons)

Image: The massive damage caused to HMS Fearless (Wikimedia Commons)

While Ithuriel was on its return journey with the 13th Flotilla, its counterpart HMS Fearless and the 12th were still on their outbound heading.

The two groups encountered each other off the Island of May at 8.23 pm.

Fearless was travelling at full speed. It had no time to attempt to dodge any of the boats of the 13th and careened into K17.

A huge hole was rent in Fearless’ bow but K17 took the brunt of the impact. The submarine took just eight minutes to sink, condemning 48 crewmen to a watery grave.

With Fearless sounding her sirens, signalling she had stopped, the remaining boats of the 12th Flotilla were close behind.

Picking up the signals from Fearless, K4 came to a halt but her trailing submarines did not. K3 narrowly missed K4 but it appeared K4 luck had run out.

K6, running at full speed, could not avoid colliding with her sister submarine. She rammed K4’s broadside, nearly cutting K4 clean in two.

Water flooded K4, dragging it down into the cold sea, when she was struck again, this time by the passing K7.

While the carnage unfolded in the North Sea, the 5th Battle Squadron reached the area. The squadron’s destroyers sailed through the waters ahead of them, oblivious to the catastrophe that had only just befallen.

Survivors from K17 were in the water when the 5th Battle Squadron sailed through, being dragged to their doom by the wake thrown up by the heavy ships.

The whole incident at the Isle of May lasted just 75 minutes.

In that time, two submarines had sunk, three had been badly damaged, the Fearless was damaged and 105 men had been killed.

A hastily convened inquiry was formed on 5th February 1918 to ascertain exactly what went wrong at May Island.

The Inquiry reported on 19th February that the Commander Leir and four K boat officers were responsible for the tragedy. However, the case against Leir was “not proved”.

The investigation and court martial of Commander Leir were kept under wraps until 1994. By that time, everyone involved in the incident had passed away.

Commemorating the casualties of the Battle of May Island

The "Battle" of May Island gets its ironic name from the jet-black humour of the British armed forces.

Whether navy, army, or air force, those serving with the Commonwealth and British militaries tended to turn to dark humour to help them deal with the trauma of incidents like May Island.

In truth, it was never a battle, more a series of tragic accidents that occurred due to poor visibility, poor submarine design, and general misfortune.

As mentioned above, 105 men lost their lives during the accident at the Isle of May.

Because they have no known grave the submariners of K4 and K17 are we commemorate can be found on our three naval memorials:

|

Memorial |

K4 Casualties |

K17 Casualties |

|

Portsmouth Naval Memorial |

21 |

11 |

|

Plymouth Naval Memorial |

0 |

10 |

|

Chatham Naval Memorial |

23 |

1 |

The bulk of the men killed during the incident at May Island came from the United Kingdom. One of their number, however, was Australian Midshipman Ernest Semple Cunningham.

Image: Midshipman Ernest Cunningham (Naval Historical Society of Australia)

Image: Midshipman Ernest Cunningham (Naval Historical Society of Australia)

Cunningham had graduated from the Royal Australian Naval College in 1913. According to his RANC entry, Ernest had been a cadet captain, a good sportsman. He had won the Grand Fleet Bantamweight Boxing Championship in 1917 for good measure.

Ernest was one of the unlucky men from K17 who perished on 31st January 1918.

One of the key things to take away from the "Battle of May" Island is that not all causalities of war are sustained in combat. A great deal of the men and women commemorated by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission died far from the front lines.

Accidents and tragedies like this one remind us the dangers of warfare do not exist solely on the battlefield. Luck, both good and bad, affects proceedings in strange ways during times of war.

As for the K Class submarines, they had proved disastrous.

Only one boat, K7, had ever fired a torpedo in anger during World War One. It failed to explode upon hitting its intended target.

Most of the K Class boats were scrapped after World War One. Three units were refurbished and reworked into M-Class submarines, of which two were lost at sea. A final planned M-Class was cancelled.

Discover more stories of the Commonwealth’s fallen with our search tools

Our search tools can help you uncover more stories of those commemorated by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission.

Use our Find War Dead tool to search for specific casualties by name, where they served, which branch of the military they served in, and more parameters.

Looking for a specific location? Use our Find Cemeteries & Memorial search tool to find all our sites. You can search by country, locality, and conflict.