22 April 2024

What is ANZAC Day?

ANZAC Day is one of the most important remembrance events in Australia and New Zealand. Learn more about this special day and how CWGC commemorates ANZAC war dead.

ANZAC Day

What is ANZAC Day?

Image: Veterans parade through the Ypres (Menin Gate) Memorial to mark ANZAC Day, 2022 (© The Last Post Association)

25 April is ANZAC Day.

It is one of the most important dates in the national calendars of Australia and New Zealand.

25 April marks the start of the Gallipoli Campaign 1915. It was the first major action fought by Australia and New Zealand during the First World War.

ANZAC Day was first marked in April 1916 on the first anniversary of Gallipoli. It has been observed every April 25 ever since and has grown to encompass remembrance of all Australian and New Zealand victims of war.

What does ANZAC stand for?

Image: An ANZAC posting the Corps' performance and newfound status following its trial by fire at Gallipoli (public domain)

Image: An ANZAC posting the Corps' performance and newfound status following its trial by fire at Gallipoli (public domain)

ANZAC stands for the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps.

The Australian and New Zealand Army Corps was originally under the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force in 1914. The original ANZAC unit was reorganised into the I and II Australian and New Zealand Army Corps in 1916, following Gallipoli.

ANZAC soldiers would continue to fight on the Western Front, including at the momentous Battles of the Somme and Passchendaele and the war-winning Hundred Days Offensive.

The Australian and New Zealand Army Corps was reformed in the Second World War, before it was once again reorganised, and troops sent to theatres around the world.

In the Second World War, Aussie and Kiwi troops fought in some of the conflict’s toughest campaigns, such as Greece and Crete, Italy, The Pacific, and North Africa.

In both wars, the ANZACs were made up of a mix of cultures and ethnicities from around Australasia. Those of Aboriginal, Māori, Torres Strait, and Pacific Island heritage served alongside comrades from European descent.

Around 416,000 Australians served in some military capacity during the First World War. That’s roughly 39% of the country's male population of military age. 222,000 New Zealand, Māori and Pacific Island troops had either been conscripted or enlisted during World War One.

The Second World War saw one million Australians enlisting to serve. Around half of these were sent overseas. 10% of Australia’s entire population served in the Australian Army alone during the war.

Why is ANZAC Day important for Australia and New Zealand?

The story of ANZAC Day begins at Gallipoli.

The Gallipoli Campaign was fought between April 1915 – January 1916 in Gallipoli, a peninsula in the Dardanelles region of modern-day Turkey.

The Allies landed at Gallipoli on April 25, with the landing zone of the Australian and New Zealand troops dubbed ANZAC Cove.

Expecting a quick, decisive campaign, Gallipoli descended into a lengthy, costly stalemate. Well organised and led, the Ottoman Army manning the peninsula’s clifftops and high ground proved a tough opponent. Allied attempts to break through were repulsed at great cost time and time again.

After eight months of bitter fighting, the decision was made to evacuate Gallipoli in December 1915. The final Allied troops left the peninsula in January 1916.

Image: Australian infantry dig in at Gallipoli (© IWM (HU 50622))

Over 55,000 Allied servicemen were killed during the Gallipoli Campaign.

The ANZACs alone lost 12,000 soldiers killed.

Though the campaign ultimately ended in defeat, the ANZAC’s experience at Gallipoli had far-reaching consequences at home in Australia and New Zealand. The actions of their soldiers, including those who lost their lives, stirred nationalist, patriotic feelings in the public.

At the start of the First World War, Australia and New Zealand were Dominions of the British Empire. This was also the case at the start of the Second World War.

However, what started at Gallipoli was the formation of Australia and New Zealand as distinct, independent nations, similar to what Canada experienced following the Battle of Vimy Ridge in early 1917.

As well as the above sentiments, ANZAC Day is also an important opportunity to reflect and remember the sacrifices made by Australians and New Zealanders of all backgrounds in all conflicts past, present, and future.

How is ANZAC Day commemorated?

Image: The Dawn Service at Buttes New British Cemetery, home to the Buttes New British (New Zealand) Memorial, 2022 (© Eric Compernolle)

ANZAC Day is marked by ceremonies and parades across Australia, New Zealand and locations closely linked to the nations’ World War experience globally.

The most famous ANZAC Day event is the Dawn Service. Held at dawn, usually around 4:30 am, at ANZAC war memorials and cemeteries, Dawn Services usually include readings, wreath layings, dedications and the familiar sounding of the Last Post on the Bugle.

Dawn holds special significance on ANZAC Day. It was at this time that ANZAC soldiers first went ashore on 25 April 1915, starting several months of bloody combat on the Gallipoli Peninsula.

Dawn services are held by Commonwealth War Graves alongside the Australian and New Zealand armed forces at cemeteries and memorials around the world. The services in Gallipoli are some of the most well-attended outside of Australia and New Zealand.

There is some debate as to when the first Dawn Service was held. Evidence suggests it may have been as early as 1923 but Australia’s first official Dawn Service took place at the Sydney Cenotaph in 1928.

New Zealand’s first dawn service came in 1939 following the declaration of ANZAC Day as a national public holiday.

How are ANZAC servicemen commemorated by Commonwealth War Graves?

The Commonwealth War Graves Commission commemorates all fallen ANZAC service men and women of the First and Second World Wars, including Aboriginal, Māori, Torres Strait, and Pacific Island personnel.

The total number of Australian and New Zealand troops commemorated by Commonwealth War Graves is:

Australia

- World War One: 62,335

- World War Two: 40,696

- Total casualties: 103,031

New Zealand

- World War One: 18,070

- World War Two: 11,926

- Total Casualties: 29,996

Where possible, each soldier will have an individual war grave bearing their name. Those with no known war grave are commemorated by name on Commonwealth War Graves war memorials around the world.

Unidentified soldiers may be buried in war graves but will be commemorated by name on a war memorial until such times as they can be identified and given a named headstone.

The locations where ANZAC troops are commemorated vary, but they help the story of the ANZACs at war. Commonwealth War Graves sites are unique in that the men are commemorated close to or on the places where they fell decades ago.

In the case of ANZAC troops, CWGC sites are found at places like Villers-Bretonneux where the Australians fought an incredible defensive action in early 1918 during the German Spring Offensive.

Gallipoli is probably the best example of this. The former battlefields are studded with CWGC cemeteries and memorials, such as Lone Pine or Chunuk Bair, standing in perpetual commemoration of the men who fought and died there.

ANZAC Cemeteries & Memorials

You can use our Find Cemeteries and Memorials tool to find all the sites around the world commemorating ANZAC servicemen.

Here is a quick look at some of them.

Lone Pine Memorial

The Gallipoli landscape is dotted with CWGC memorials; permanent reminders of the terrible fighting that took place here over a century ago.

Several memorials commemorating the war dead of the Gallipoli Campaign were built after the First World War:

- Hill 60 (New Zealand) Memorial

- Helles Memorial

- Chunuk Bar (New Zealand) Memorial

- Twelve Tree Copse Memorial

- Lone Pine Memorial

Lone Pine sat in the Southern part of the ANZAC attack zone. Strategically important, it was captured briefly in the Gallipoli landing’s early staged, but then retaken and held by Ottoman forces.

The 1st Australian Brigade captured Lone Pine in August 1916 and held onto for the remainder of the campaign.

Lone Pine Memorial stands at the heart of the former battlefield. Instead of bullets and bloodshed, the site offers more peaceful, contemplative surroundings today.

Just shy of 5,000 servicemen, predominantly Australians but with some Kiwis and a handful of Brits, are commemorated by name on the Lone Pine Memorial.

Chunuk Bair (New Zealand) Memorial

850 or so New Zealand casualties are commemorated by the Chunuk Bair (New Zealand) Memorial.

Chunuk Bair in Gallipoli’s central foothills was attacked as part of the Battle of Sari Bair between 6-10 August 1915.

The attack was led by the New Zealand Infantry brigade, supported by the New Zealand Mounted Rifles. Kiwi units involved in the battle included the

Wellington Infantry, the Auckland Infantry, the Auckland Mounted Rifles and the Otago Battalion. They were supported by a number of British and Indian Army regiments.

The Allied forces initially managed to hold Chunuk Bair but they were repulsed at great cost following an overwhelming Ottoman attack led by Mustapha Kemal Pasha.

The loss of Chunuk Bair marked the end of the effort to reach the central foothills of the peninsula and on this sector of the front, the line remained unaltered until the evacuation in December 1915.

El Alamein War Cemetery

Tens of thousands of ANZACs served in North Africa in the fight against the Axis powers.

The fighting in the baking heat and dust of the North African deserts had not been going in the Allies’ favour prior to 1942. But, with a reorganisation of the men there into 8th Army under General Bernard Montgomery, the tide began to turn.

The Second Battle of El Alamein, fought in October 1942, was an enormous success. Smashing through the forces of German Field Marshal’s Afrika Corps, 8th Army broke its opposition, forcing the Wehrmacht into full retreat out of Egypt into Libya.

8th Army was a truly Commonwealth unit, taking in forces from across the British Empire, including Australia and New Zealand.

El Alamein pushed all its combatants, including the ANZACs, to their limit, but ended in a decisive Allied victory. ANZAC soldiers played a great role in the battle, their skill and courage under fire exemplified by the awarding of three Victoria Crosses to ANZAC soldiers for their actions at El Alamein.

The dead of El Alamein are commemorated at El Alamein War Cemetery, the largest Commonwealth War Graves cemetery in North Africa.

The cemetery holds roughly 6,500 identified burials. Of this total, about a third are Australian and New Zealand soldiers and enlisted men,

Those casualties of El Alamein with no known war grave are commemorated by name on the EL Alamein Memorial. Approximately 1,500 ANZAC servicemen are commemorated by name on the memorial.

Port Moresby War (Bomana) Cemetery

Papua New Guinea was subject to intense jungle warfare during the Second World War.

It lies very close to Australia and so was captured by the Imperial Japanese as a means to strike at the Australian heartland. From theatres in the Mediterranean, Australian troops were hastily pulled back to defend their homeland.

Alongside allies from the US, the Australians fought a determined campaign to kick the Japanese out of Papa New Guinea and the neighbouring Solomon Islands, particularly the island of Bougainville.

Offensive operations began in late 1943 and continued until the Japanese surrender in August 1945.

Those who died in the fighting in Papua and Bougainville are buried in Port Moresby (Bomana) War Cemetery. Their graves brought in by the Australian Army Graves Service from burial grounds in the areas where the fighting had taken place.

Of the roughly 3140 identified burials at Port Moresby (Bomana) War Cemetery, just over 3,100 are Australian. A number of British and Dutch POWs are buried here too, alongside a handful of Royal New Zealand Air Force personnel.

Cassino War Cemetery

While the war in North Africa was tough, perhaps the most brutal, hardest campaign fought by the Allies in the West was Italy.

Invaded by the Allies in late 1943, Italy was seen as a softer target than other places, such as occupied France. The truth could not have been more different.

In a gruelling campaign that lasted until the German surrender of May 1945, the Allies inched their way up Italy’s unforgiving terrain to reclaim it from the occupying forces.

ANZAC troops in Italy were mostly New Zealanders. The Royal Australian Air Force flew sorties in some of the key Italian engagements, but the Kiwis were the predominant ANZAC ground forces.

One of the most infamous episodes of the Italian campaign was the Battle for Monte Cassino. A foreboding peak overlooking important mountain and valley passes, Monte Cassino was strategically important, especially for the Allied advance on Rome.

No less than four battles were fought to capture Monte Cassino, finally being taken on May 18 1944.

The cost had been high, reflected in the 4,200 burials in Cassino War Cemetery.

Of those, about a tenth are New Zealanders. 450 Kiwis are buried at Cassino, representing their important contribution to the victory.

2,100 New Zealanders were killed in Italy, commemorated across 29 CWGC sites. The 450 at Cassino represents around 20% of the number of Kiwis killed during the Italian Campaign.

ANZAC casualty stories

ANZAC Day allows us to think and reflect on all Australian and Kiwi’s servicemen and women’s sacrifice during the World Wars, no matter their heritage.

Here is a small selection of ANZAC stories taken from our online archive For Evermore to read on this and each ANZAC Day.

Corporal Alexander Burton VC

Image: Alexander Burton VC (Australian War Memorial)

Image: Alexander Burton VC (Australian War Memorial)

Alexander Burton was born in Kyneton, Victoria, on 20 January 1893. Prior to the war, Alexander worked at the same department store as his father in the ironmongery department.

Alexander enlisted in the Australian Imperial Force in August 1914, shortly after the outbreak of the First World War, joining the 7th Battalion.

Although he was present at the 1915 Gallipoli landings, Alexander did not take part in the fighting. He was being treated for a throat infection so watched the troops come ashore from the deck of a hospital ship.

Soon, though, Alexander was in the trenches, fighting across the Gallipoli Peninsula with the 7th Battalion.

Early on the morning of the 9 August, the Ottoman forces defending the peninsula launched a fierce counterattack on a trench newly captured by the 7th Battalion.

Alexander, along with Lieutenant Frederick Tubb and Corporal William Dunstan, were holding the trench.

The advancing Ottoman Turks managed to advance up the trench and blew up the sandbag barricade erected by the Aussies. Together with Tubb and Dunstan, Alexander repaired the barricade.

Twice more the barricade was destroyed; twice more the attacks were driven off and the barricade rebuilt.

Alexander was killed by an enemy bomb while rebuilding the barricade parapet. He has no known grave and so is commemorated on the Lone Pine Memorial.

Alexander was awarded a Victoria Cross for his bravery at Lone Pine. His medal citation reads:

“For most conspicuous bravery at Lone Pine Trenches on the 9th August, 1915.

“In the early morning the enemy made a determined counter-attack on the centre of the newly captured trench held by Lieutenant Tubb, Corporals Burton and Dunstan and a few men. They [the enemy] advanced up a sap and blew in a sandbag barricade, leaving only one foot of it standing, but Lieutenant Tubb with the two Corporals repulsed the enemy and rebuilt the barricade.

“Supported by strong bombing parties the enemy twice again succeeded in blowing the barricade, but on each occasion they were repulsed and the barricade rebuilt, although Lieutenant Tubb was wounded in the head and arm and Corporal Burton was killed by a bomb while most gallantly building up the parapet under a hail of bombs.”

Lieutenant Tubb and Corporal Dunstan were both awarded VCs. Tubb later earned a promotion to Major and later killed in action on the Western Front.

Brigadier James Hargest CBE MC DSO**

Image: Brigadier James Hargest (public domain)

Image: Brigadier James Hargest (public domain)

Brigadier James Hargest had a remarkable military career spanning both World Wars.

Born on 4 September 1891 in Gore, Southville, New Zealand, James had served with the local militia before enlisting in the New Zealand Expeditionary Force in August 1914.

Quickly commissioned as a Second Lieutenant, James rapidly rose through the ranks. He was a brave, conscientious officer who led from the front. Throughout his career, James could be found at the front, leading his men through courage and example.

He was severely wounded at the Battle of Chunuk Bair in August 1915 at Gallipoli, leading to a long period of convalescence.

In September 1916, during the Battle of the Somme, James, by this time a Major, earned the Military Cross. He ended the war a Lieutenant-Colonel and awarded a Distinguished Service Order for his conduct and leadership.

In the interwar years, James settled in New Zealand with wife Mary. The pair owned a farm near Invercargill and raised four children there. James got involved in local politics, becoming MP for Awarua.

Come the Second World War, James volunteered his services again. He was initially declared only fit for home guard service, but, after appealing to New Zealand Prime Minister Peter Fraser, he was made Brigadier of the 5th Brigade, New Zealand 2nd Division.

The Kiwis and James served in several Mediterranean theatres, including Greece, Crete, and Libya. All three campaigns ended in defeat for the British Empire forces.

In November 1941, during Operation Crusader, the operation to relieve the important Libyan port city of Tobruk, James, his command staff, and 700 men were taken prisoner of war.

James was taken to Italy to Campo 12: a POW camp specifically for officers of Brigadier or higher rank.

James was held in captivity until March 1943 when he and a group of six officers daringly broke out of the prison. James was one of only two escapees to make it out of Italy. With the help of the French Resistance, he was able to make is way through Occupied France to Spain and finally to England.

Despite his captivity, James was determined to get back out in the field, eschewing a desk job. He was appointed New Zealand’s Military Observer for the D-Day Landings, attached to the 50th British Division.

Going ashore on D-Day itself, James was wounded in action in Normandy in June 1944.

With the Allies now pushing into the Normandy countryside, James was given a new role. He was appointed commander of the 2NZEF Reception Group, a unit set up to help rehabilitate liberated Kiwi prisoners of war.

Sadly, James was killed on 12 August 1944. He was struck by shellfire while on a farewell visit to the 50th British Division. He is buried at at Hottot-les-Bagues War Cemetery.

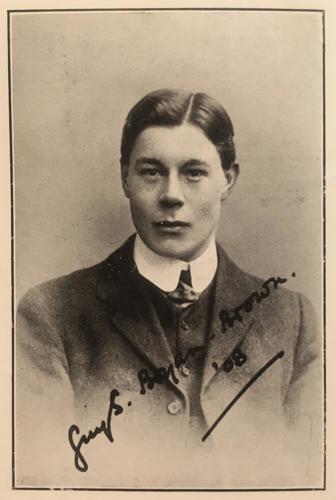

The Rev Guy Spencer Bryan-Brown

Image: The Rev Guy Spencer Bryan-Brown (public domain)

Guy Spencer Bryan-Brown was born the son of the Rev. Willoughby Brown and his wife Grace on 3rd July 1885.

He was born in Gloucestershire and was educated at St Andrew/s School in Southborough. Guy moved onto Tonbridge School before going up to university at Downing College, Cambridge.

Guy was a keen sportsman in his youth. He captained the Downing cricket and hockey teams and tennis club, earning a Cambridge blue for his hockey prowess.

At Cambridge, Guy later moved to Ridley Hall, studying theology, reading for Holy Orders and qualifying for a teaching diploma. In 1908, he was appointed

In 1908 he was appointed to a Mastership at Trinity College, Glenalmond, and was ordained in 1909 before proceeding in 1913 to Christ’s College, Christchurch, Canterbury, New Zealand, as Chaplain-Master. There he continued his sporting interests, including representing Canterbury in cricket.

In 1913 the, now, Reverend Bryan-Brown became Chaplain to Christ’s College Cadet Corps, and Chaplain to the Forces (4th Class) with the New Zealand Chaplains Department in March 1914. In the Christmas holidays of 1916-17 he was at Trentham Training Camp and was assigned as Temporary Army Chaplain (and Captain) with the 21st New Zealand Expeditionary Force 21st Reinforcements and later with the 3rd Canterbury Battalion.

Originally, Guy declined the position but reapplied in January 1917. He sailed to England on 14th February 1917 as a temporary chaplain with the 21st Reinforcements and served with the Expeditionary force from 29th May onwards.

On 4th October 1917, he was killed in action at an aid post near Ypres, during the ANZAC advance towards Passchendaele. A Staff Captain wrote: "The doctors who were with him say that he rendered invaluable assistance during the day in bringing in and dressing the wounded, and I am sure, from what I know of him, that he never spared himself or thought for one moment of the risk he was running, so long as he could help those who were in need”.

There are various reports surrounding the circumstances of his death. However, a fellow Chaplain stated that he was "bust blocking up a window of a dressing station from the outside, when three shells came in quick succession. I saw him fall staggering sideways, and I rushed to him at once, but he was dead… If ever a man gave his life away for others, that man was G. Bryan-Brown".

As he has no known grave, Guy is commemorated today on the Tyne Cot Memorial.

Got an ANZAC story to tell? Share it on For Evermore

For Evermore: Stories of the Fallen is our online resource for sharing the memories of the Commonwealth’s war dead.

It’s open to the public to share their family histories and the tales of the service people commemorated by Commonwealth War Graves so that we may preserve their legacies beyond just a name on a headstone or a memorial.

If you have a story of someone who served with the ANZACs to tell, we’d love to hear it! Head to For Evermore to upload and share it for all the world to see so we can remember them on this ANZAC Day and all to come.