08 August 2022

What is the largest WW1 memorial?

There are more than 526,000 Commonwealth casualties of World War One commemorated on our memorials across the globe. Our biggest memorials bear the names of tens of thousands of Commonwealth war dead, but our largest WW1 memorial is the Thiepval Memorial to the Missing of the Somme – in fact, it’s our largest memorial of all.

The largest World War One Commonwealth Memorial in the world

Many of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission’s largest WW1 memorials stand on the former battlefields of the Western Front. The trench warfare in France and Belgium meant high numbers of missing casualties, whether fallen anonymously in no-man’s land, or buried in hastily dug graves soon lost in maelstrom of mud and bursting shells of the Flanders battlefields.

Our largest World War One memorial is the Thiepval Memorial to the Missing of the Somme, which commemorates more than 72,000 officers and men who fell during the Great War.

The largest WW1 war memorials in France

Stretching from the North Sea coast, down to the alpine border with Switzerland, the trenches of the Western Front cut a ruinous swathe through the countryside of northern France and Belgium. Troops from across the Commonwealth were sucked into a conflict which in time degenerated into a grinding battle of attrition against their German counterparts, costing millions of lives.

Our three largest Memorials to the Missing in France are:

Number 1: Thiepval Memorial

The Battle of the Somme is infamous as one of the bloodiest battles in human history and one that has become synonymous with the trench warfare of the Western Front. A series of large-scale offensives, the battle lasted for months, with soldiers from across Great Britain, France and the Commonwealth attacking multiple points on the German line. The first day of the battle, 1 July 1916, saw more than 57,000 British soldiers killed, wounded, or missing, the worst single day in British military history.

By the end of the battle, in November 1916, more than a million men on both sides were dead or wounded. Some of those who fell where buried by their comrades on the battlefield or in burial grounds located near medical facilities. After the war the search for the fallen continued and those that could be recovered were often buried in large ‘concentration’ cemeteries such as Serre Road Cemetery No. 2 and Caterpillar Valley Cemetery, but many more were not found and are listed on our memorials.

Thiepval Memorial is the largest and most well-known of the memorials to the missing of the Somme. The vast majority of those commemorated here served in British units, however there are also 832 soldiers of the South African infantry listed on its panels.

The memorial also stands as a joint Anglo-French battle memorial to commemorate the joint nature of the battle and the alliance between the British and French Empires; the Union Flag and Tricolore fly above the memorial, and the Thiepval Anglo-French Cemetery stands at the foot of the memorial and contains equal numbers of French and Commonwealth burials.

When was the WW1 memorial built?

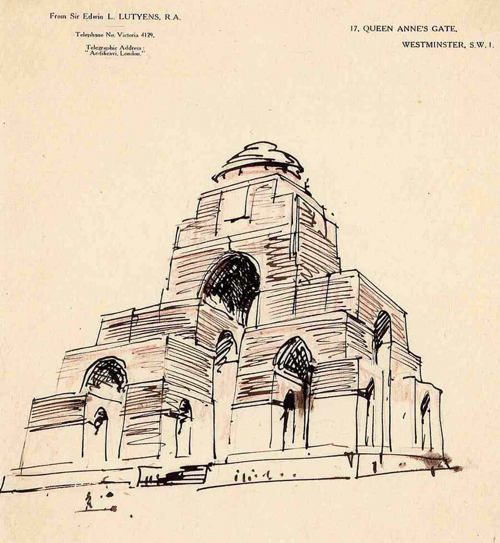

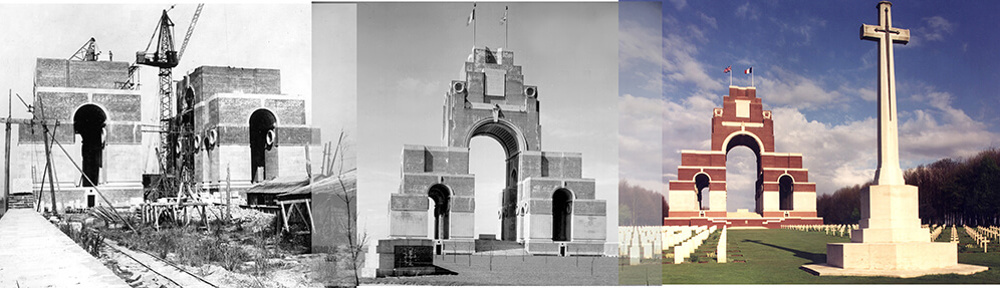

The memorial was built between 1928 and 1932 and was designed by Sir Edwin Lutyens, one of the CWGC’s Principal Architects. It was officially unveiled on 1 August 1932 by the Prince of Wales.

The memorial was built between 1928 and 1932 and was designed by Sir Edwin Lutyens, one of the CWGC’s Principal Architects. It was officially unveiled on 1 August 1932 by the Prince of Wales.

Thiepval memorial list of names

There are more than 72,000 names engraved on the memorial. They are British and South African officers and men who died on the Somme before 20 March 1918, although the vast majority died between July and November 1916.

Those commemorated here have a huge number of honours and awards; there are more than 760 Military Medals, more than 100 Military Crosses, countless Mentions in Dispatches and even 7 Victoria Crosses.

Captain Eric Norman Frankland Bell is one of the Victoria Cross winners commemorated on Thiepval Memorial. Originally from County Fermanagh in Ireland, Captain Bell was serving with the 9th Battalion, Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers, part of the 36th (Ulster) Division. As part of an advance on a German redoubt, Bell’s men were held up by a German machine gun. Bell crept forward alone and shot the machine gunner, freeing up the advance.

Later in the attack, Bell single-handedly attacked three German trenches, throwing bombs at the enemy to clear the way. He later defended against a German counterattack but was killed rallying and reorganising infantry parties that had lost their officers. His citation ends “All this was outside the scope of his normal duties with his battery. He gave his life in his supreme devotion to duty.” He died on 1 July 1916, aged 20.

Thiepval memorial restoration

Throughout 2021-2022, the Thiepval Memorial has been undergoing a massive restoration project. This is phase two of a project that began in 2016.

Like all of our sites, the memorial receives ongoing maintenance work, however at close to 90 years old, it needed some extra attention.

Much of the work is behind the scenes. The memorial has a complex internal drainage system which channels rainwater through the memorial itself to drain away. This needed a significant upgrade.

Work is also needed on the memorial’s iconic red brick. The brick surrounds a concrete core, and while the core itself remains intact, the brickwork needs repointing, and in some cases, securing back onto the concrete.

The last of the work will be on the Portland stone panels that line the memorial. These bear the names of those commemorated here, and we are taking the opportunity to restore and update these panels.

These tasks are no small feat, especially as we are committed to working in a sustainable manner, however they are vital in ensuring that the memorial continues to commemorate the men and women listed on its walls for another 90 years.

Number 2: Arras Memorial

Arras Memorial stands adjacent to Faubourg D’Amiens Cemetery in Arras, near Lens. It was the scene of a major British offensive on the Western Front in 1917, which cost thousands of lives on both sides.

Arras had been on the front line throughout 1914 and 1915 and there had been heavy fighting for the high ground to the north. The German positions were formidable with multiple lines of trenches, concrete block houses and deep dugouts manned by veteran German soldiers.

On 9 April 1917, British Empire forces launched a major offensive around Arras. In the south some units advanced more than five kilometres into German-held territory, while to the north Canadian troops captured Vimy Ridge. During the following weeks, fierce German resistance and poor weather prevented any further significant advances. By the end of the offensive on 16 May, some 300,000 men on both sides were wounded, missing or dead.

The Memorial commemorates more than 35,000 British, South African and New Zealand servicemen who died in the region between 1916 and 7 August 1918 and who have no known grave, with many of them killed during the Battle of Arras.

Also at this site is the Arras Flying Services Memorial which bears the names of nearly 990 British Empire airmen of the First World War who died in France and have no known grave, more than 65 of whom died in April 1917.

Number 3: Loos Memorial

Loos Memorial can be found at Dud Corner Cemetery, nearby to the site of a German strongpoint to the north-west of Lens. The name ‘Dud Corner’ came from the large number of unexploded shells found when the area was cleared to create the cemetery after the end of the war.

The memorial surrounds the cemetery and commemorates more than 20,000 servicemen of World War One who died in the region and who have no known grave.

One of the largest battles in this region was the Battle of Loos in September and October 1915. This was the last attempt to break through the German lines before the onset of winter 1915. Despite the first use of poison gas by British forces, the German defences proved too strong, and losses were heavy for little gain. The casualties on 25 September were the worst yet suffered in a single day by the British Army, including some 8,500 dead. In total, the battle resulted in casualties of more than 50,000, of whom some 16,000 lost their lives.

The failure also meant that Sir John French, the Commander in Chief of the British Expeditionary Force, was recalled and was replaced by Sir Douglas Haig.

Largest WW1 memorial in Belgium

Within three weeks of the United Kingdom declaring war on Germany in August 1914, the armies of the two powers clashed for the first time at Mons in Belgium. This began four years of bloody fighting on Belgian soil, not ending until the day of the Armistice when the last British casualty of the war was shot and killed while on patrol outside Mons.

Our three largest Memorials to the Missing in Belgium are:

Number 1: Ypres Menin Gate Memorial

One of the most iconic CWGC memorials, the Menin Gate in the city of Ieper commemorates more than 54,000 officers and men who died in the Ypres Salient during World War One.

The fighting around Ypres was some of the bloodiest of the war, a “salient” or bulge, in the lines was initially formed when the British Army secured the town of Ypres in 1914, pushing the German forces back to the higher ground to the north, east and south of the town.

In April 1915, the German Army tried to retake the town in an attack which saw the first instances of poison gas used by either side and was the first major engagement fought by Canadian forces. Following this attack, which had seen an Allied withdrawal and shortening of the line, the front lines remained predominantly static, leading to the stalemate of trench warfare.

The fighting erupted once more in 1917 with the Third Battle of Ypres, also known as Passchendaele. This was an Allied offensive against the well-prepared German positions on heights around the town but on ground the Germans would be compelled to defend. In June 1917, a preliminary attack saw the capture of the Messines Ridge but delays in moving forces north to Ypres meant that the main offensive didn’t begin until 31 July. Despite initial success, determined defenders and bad weather conditions hampered the offensive, and significant advances were forestalled. The fighting degenerating into an attritional battle for the village of Passchendaele which was finally won at great cost by the Canadian Corps in November.

In April 1918, the German Army launched their own major attack near Ypres, part of their wider Spring Offensive. But despite determined German attacks, allied forces did not break, and while the line was pushed back German troops were unable to breakthrough. A few months later in September, Allied forces went on the offensive and began an advance which drove the German army back through Flanders only ending with the Armistice.

The fighting across the Ypres Salient cost thousands of lives on both sides. Today, the Menin Gate commemorates those that fell on the salient, a physical link between the Ieper and its history. Every evening at 8pm, the famous Last Post ceremony is held at the memorial in tribute to those who lost their lives there.

The restoration of the Menin Gate Memorial began in 2023 and is now completed, preserving it for decades to come. Discover more about this remarkable process today.

Read more about the Menin Gate Memorial RestorationNumber 2: Tyne Cot Memorial

CWGC’s largest cemetery, Tyne Cot Cemetery, is also home to the second largest memorial in Belgium. Like the Menin Gate, Tyne Cot Memorial commemorates close to 35,000 officers and men who died in the Ypres Salient in the First World War and who have no known grave.

The cemetery and memorial are built on the remains of a collection of German pillboxes, with the Cross of Sacrifice mounted on the largest one - at the suggestion of King George V, who visited the site in 1922. The name Tyne Cot is said to have come from the Northumberland Fusiliers, who thought the German fortifications were reminiscent of the Tyneside cottages of home.

Tyne Cot Memorial bears the names of nearly 34,000 British, and over 1,000 New Zealand servicemen. Initially the names of the British servicemen were meant to be recorded on the Menin Gate, but the sheer number of casualties meant that it was impossible to fit them all on its walls. Instead, those who died before 16 August 1917, with some exceptions, are commemorated on the Menin Gate, while those who died after are at Tyne Cot.

Number 3: Ploegsteert Memorial

More than 11,000 servicemen are commemorated on Ploegsteert Memorial. The majority of those commemorated here are British, commemorated alongside 13 South Africans, all casualties of World War One.

The memorial stands in Berks Cemetery Extension, 12.5kms south of Ieper (Ypres), close to the Belgian-French border.

Unlike the memorials found in the Ypres Salient, Ploegsteert is on an area of the front lines that was comparatively quiet. The early stages of the war saw fierce fighting around Ploegsteert Wood, but this had quietened down by 1916 to the point where there are only 346 names listed on the memorial of men that died in 1916 and 1917.

More than 5,300 of the names listed on the memorial, close to 50% of the total, are those who died in April 1918 during the German Spring Offensive, which saw multiple German attacks down the length of the Western Front, aimed at defeating the Allies before they could be reinforced by American troops.

Many of those on Ploegsteert Memorial who died that April did so during the Battle of the Lys, part of the German Offensive that aimed to push British forces in Belgium back to the channel. While the German attack gained ground, they ultimately failed to capture Hazebrouck, one of the main objectives of the attack. Eventually, and at a cost of hundreds of thousands of lives, the German Spring Offensive was stopped.

What’s the biggest WW1 war memorial in the UK?

As an island and a seafaring nation, it will be of little surprise to know that the biggest CWGC war memorials in the United Kingdom commemorate those who lost their lives at sea during the world wars.

The war at sea was a key theatre in both conflicts. Control of the seas was vital for moving men and supplies from Britain into western Europe, or to the other fronts. Some memorials in the UK, such as Hollybrook Memorial or Runnymede Memorial commemorate war dead of only one war, but the largest memorials in the UK commemorate men and women who died in both world wars.

Our three largest WW1 Memorials to the Missing in the UK are:

Number 1: Tower Hill Memorial

Just a stone’s throw from the Tower of London, Tower Hill Memorial stands on the banks of the river Thames, a link to London’s past as the cornerstone in global trade and maritime commerce.

The memorial’s location was chosen to reflect the service of those listed on its walls. The men and women commemorated here are those who died while serving in the Mercantile Marine (later Merchant Navy) and Fishing Fleets, Britain’s lifelines during the war.

Merchant ships were extremely vulnerable to attack as they were often slower and less manoeuvrable than military craft, and often with only a token defensive armament. Many craft were attacked at sea, and, even when close to home, would often have to navigate minefields laid at friendly ports. Throughout World War One, losses were high, but peaked in 1917 when the German government announced ‘unrestricted submarine warfare’ - attacking enemy merchant vessels without warning.

Countermeasures, such as the convoy system, were put in place, but by the end of the war, more than 3000 merchant ships had been lost.

The First World War section of Tower Hill Memorial, which was unveiled by Queen Mary in December 1928, commemorates more than 12,000 Mercantile Marine casualties who have no grave but the sea.

Number 2: Portsmouth Naval Memorial

By the end of World War One, there were more than 45,000 men and women who had died while in service in the Royal Navy, the majority lost at sea.

To commemorate these casualties, three memorials were built at the Royal Navy’s principal manning ports: Plymouth, Portsmouth and Chatham. These memorials were large obelisks, designed to act as leading marks for shipping.

There are close to 10,000 casualties of World War One listed on the Portsmouth Naval Memorial, of which around 3,400 are casualties of the Battle of Jutland, one of the most well known naval battles of the war.

The battle was the last major battle fought primarily by battleships and took place on 31 May 1916, lasting until the early hours of the next morning. More than 300 ships - ranging from powerful Dreadnoughts through to smaller, manoeuvrable Destroyers and torpedo boats - met in battle in the North Sea. Close to 10,000 personnel died during the battle, more than 6,700 of which were British.

The outcome of the battle was inconclusive. The Royal Navy lost a greater number of men and ships, but the German navy retreated to Port and was prevented from accessing the channel and the Atlantic Ocean for the rest of the war. Neither side suffered enough losses to suggest a conclusive victory for either navy.

Number 3: Plymouth Naval Memorial

Like Portsmouth and Chatham, Plymouth Naval Memorial is a large obelisk standing in Hoe Park, close to the seafront.

It commemorates more than 7000 sailors of World War One, as well as close to 16,000 World War Two war dead. More than a quarter of those commemorated here from World War One died in the Battle of Jutland and have no other grave than the sea.

Lieutenant Commander William Edward Sanders, from Auckland, New Zealand, is commemorated here. He won the Victoria Cross in 1917 when his command, HMS Prize, was attacked by a German submarine.

HMS Prize was a Q-Ship, a warship designed to look like a merchant vessel to encourage enemy attacks. Once engaged, they would use hidden weaponry to counterattack.

Prize was attacked by U-93, a German submarine, on the evening of 30 April 1917. Despite being damaged by the submarine’s deck cannon, and with many of the crew suffering injuries, Sanders held firm, sending out some of his crew on a lifeboat to further sell the idea that his ship was in trouble.

As the submarine approached, Prize opened fire, damaging the submarine and causing some of its crew - including the captain - to fall from its deck. The submarine submerged and escaped, and despite its severe damage, Prize was able to return to port.

Such was the secret nature of the Q-Ships’ operations, the details of Sanders’ exploits were not publicly released at the time; his citation in the London Gazette simply stated: "In recognition of his conspicuous gallantry, consummate coolness, and skill in command of one of H.M. ships in action."

Largest WW1 Memorials elsewhere in the world

Conflict between the European powers did not mean that the fighting in World War One was limited to the battlefields of Europe. CWGC commemorates the men and women who died in the war in our cemeteries and memorials across the globe.

Some of our largest memorials around the world are:

Basra Memorial

The campaign in Mesopotamia (modern day Iraq) was fought between British and Indian Army forces against the Ottoman Empire. In terms of the numbers engaged, it was the largest theatre of operations outside of Europe for the British Empire during the First World War.

British and Indian forces suffered casualties of more than 85,000 killed, wounded and missing in Mesopotamia. It was a campaign fought largely by the Indian Army, often in challenging conditions with limited supplies and medical care.

Basra Memorial commemorates more than 40,620 servicemen of the British Empire who died in Mesopotamia and have no known grave. More than 33,250 of those commemorated served with the Indian Army.

Helles Memorial

The Gallipoli campaign is one of the most ill-fated operations of World War One. Aiming to knock the Ottoman Empire out of the war and open up vital supply routes to Russia, Allied forces made an amphibious landing on the Gallipoli peninsula in the spring of 1915.

A combined Commonwealth and French force made a series of landings on Gallipoli in April 1915. The main landing was at Cape Helles where five beaches were selected for landing, codenamed S, V, W, X and Y. The landings at V and W beaches in particular saw heavy casualties, and despite more successful landings on the other beaches, the attack faltered far short of the first day’s objectives. To the north the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps (Anzac) landed at what became known as Anzac Cove. Here too the Anzacs were met my determinate resistance and difficult terrain, the men struggling to gain and then maintain a foot hold amongst the perilous cliffs and gullies. The invasion had been conceived as an alternative to the trench warfare of the Western Front, but almost immediately the campaign became bogged down in brutal trench warfare.

Despite reinforcements and further landings at Suvla Bay the invasion proved a failure and Commonwealth troops were evacuated beginning December 1915, the last troops leaving Helles in January 1916.

The casualties of the Gallipoli campaign are commemorated on Gallipoli and in places such as Malta and Egypt where many wounded troops were evacuated and later died as a result of their injuries or from illness, while missing naval casualties of the battle are commemorated on the naval memorials at Chatham, Plymouth and Portsmouth. Helles Memorial is the largest CWGC memorial on the peninsula, with more than 20,000 war dead commemorated there.

Delhi Memorial (India Gate)

Designed by Sir Edwin Lutyens and unveiled in 1931, the Delhi Memorial commemorates 13,300 Commonwealth servicemen who died in Indian or beyond the frontiers during World War One, many of whom during the Third Anglo-Afghan War, who have no known grave.

As well as commemorating those Commonwealth casualties, Delhi Memorial is also a national memorial to the 84,000 Indian servicemen who died serving across the globe and are buried in one of our cemeteries or commemorated by name at sites like the Neuve-Chapelle Memorial.

Search for WW1 memorials of all sizes

You can use our cemetery and memorial search tool to plan a visit to our war memorials. You can use it to search for sites of all shapes and sizes, from your local churchyard cemetery to our largest commonwealth war cemetery and all of our iconic memorials around the world.