21 August 2023

What was the Imperial War Graves Commission doing in 1918?

As World War One raged across the world, the Imperial War Graves Commission continued its growth journey in the pivotal year of 1918. Discover the history of the Commission today.

The Imperial War Graves Commission in 1918

The Origins of the Commission

Image: Soldiers clear unexploded mines away from the site of an Imperial War Graves Commission cemetery somewhere on the Western Front.

The Imperial War Graves Commission, our name prior to 1960, was founded by Royal Charter on 21 May 1917 with Brigadier-General Sir Fabian Ware at its head.

The journey to the Commission’s founding is an interesting one.

In 1914, Fabian was placed in control of a mobile British Red Cross unit on the Western Front.

At the start of the First World War, marking war graves and burials was more of an improvised activity. There was no standardisation and burial grounds were often swept away on the tides of war.

Recognising this, Ware lobbied higher authorities to improve processes. His Red Cross unit was transferred to the British Army and became known as the Graves Registration Commission (GRC).

In 1916, the GRC’s remit was expanded with the name changed to reflect its new additional duties: the Directorate of Grave Registration and Enquiries (DGRE).

The two organisations were essentially the same. Under Ware, the DGRE still handled marking and recording existing graves, but now also:

- Handling enquiries from the bereaved relatives

- Searching for missing bodies

- Moving isolated graves or burial plots into large cemeteries

- Identification of found or disinterred bodies

There was as much of a need to look to the future of the war graves post-war. Cemeteries and war memorials would have to be established to commemorate the sacrifice of so many young men and women at war.

Image: Sir Fabian Ware, founder of the Imperial War Graves Commission

Image: Sir Fabian Ware, founder of the Imperial War Graves Commission

In January 1916, Military Authorities suggested the creation of a special body to take over from the DGRE once the Great War was over. This was established as the National Committee for the Car of Soldiers’ Graves.

However, Ware thought this was too limited in scope. Men and women had fought, served, and died in the service of the Empire from all over the globe.

Canadians, Indians, Australians, New Zealanders, South Africans, and a whole host of nationalities, cultures, and ethnicities fell across the globe during the war.

Sir Fabian, therefore, proposed this should be an Empire-wide organisation. With the help of Edward, Prince of Wales, Ware submitted a memorandum to the Imperial War Conference in 1917, to make his proposals widely known.

The memorandum was accepted, and the Imperial War Graves Commission was born. Our work, as the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, continues to this day.

But what were we doing in 1918: the climactic year of the First World War?

Marking & registering war graves

Image: DGRE personnel out in the field conducting their important war graves work

The duties of the Directorate of Grave Registration and Enquiries and the Commission began to overlap in 1918 but the DGRE was still focussed on its core mission: marking and registering war graves.

According to an October 1918 report on the work of the DGRE, 94,649 graves and been registered and identified and marked, in addition to recording 57,148 burials yet to be located and verified.

The report is keen to stress these graves had been identified in many World War One theatres of combat.

War graves and reburials are mentioned in Gaza, Palestine in modern-day Israel, for example. Other locations touched on include the former Somme battlefields, as well as in East and South Africa.

The report also mentions how combat affected the work of DGRE units out in the field.

In April 1918, a major German advance known as the Spring Offensive smashed into Allied lines. The Allies held the line but lost as much as 40 miles worth of territory.

The German advance and Allied counterattack saw armies trample back and forth across over “50% of the registered graves and cemeteries” in France and Belgium. Such activity was common in the early days of the Commission and demonstrate the challenges of identifying war burials and graves in an active warzone.

Correspondence and contact with relatives

An organisation like the Imperial War Graves Commission had never existed before. As such, the Commission staff would deal with reams of letters, missives, and messages from the general public.

In 1918, according to the DGRE report, the organisation dealt with “satisfactorily” 186,663 letters of enquiry from members of the public.

Many of these often-heartbreaking messages were from people wishing to discover the location of their loved ones’ war graves, such as the letter below from the sister of Lieutenant Arthur Conway Osbourne Morgan.

Arthur’s sister, G. H.H. Morgan, wrote to the Commission in September 1918 enquiring as to her brother’s whereabouts in the Hohenzollern Redoubt near Loos-en-Gohelle, northern France. The Hohenzollern Redoubt was a German Army strongpoint, captured in October 1915 before being retaken later on in the war following an Allied advance.

Miss Morgan’s missive mentions the Allied advance of 1918, the Hundred Days Offensive, showing how both relatives and grave authorities had to react to changing battlefield situations to discover and identify war graves.

Establishing Commission Principles

With 1918 being very early on in the Commission’s history, many meetings, committees, and gatherings were held to outline the principles that guide us to this day.

A wide variety of reports and meeting minutes drawn from our archives show several important aspects of the Commission were discussed or established in 1918.

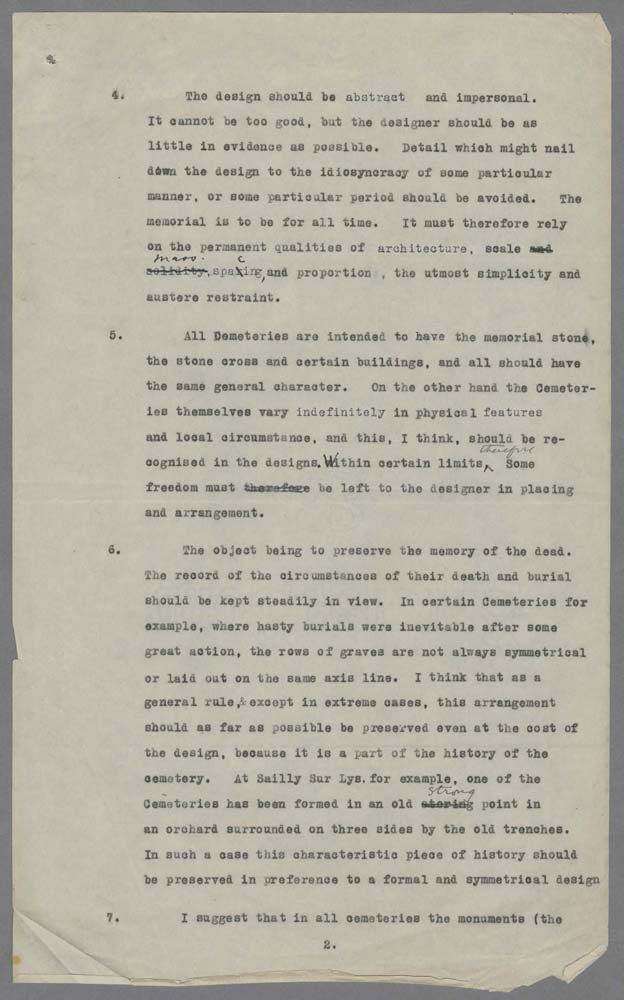

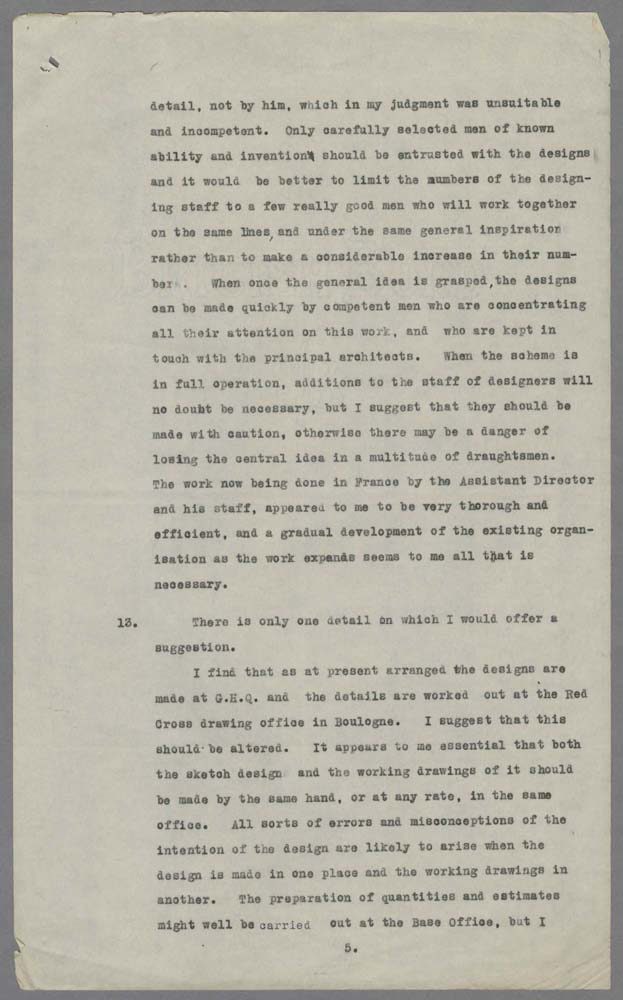

Blomfield’s Report

Sir Reginald Blomfield was one of the three original principal architects of the Imperial War Graves Commission. Together with Sir Edwin Lutyens and Sir Herbert Baker, Blomfield created the aesthetics that have become iconic with Commission sites.

In February 1918, Sir Reginald undertook a tour of some 40 British and Commonwealth cemeteries across northern France and Flanders in Belgium.

Sir Reginald recorded his observations and notes after carefully surveying these sites. His notes include several ideas that have gone on to influence how we operate and commemorate war dead, including:

- Universal look and feel to Commission cemeteries & memorials

- Complete focus on the commemoration of the men and women involved

- Feature and preservation of historical elements of each site where possible

Discussions between the designers, architects, and relevant authorities would continue through 1918 and into the post-war period but many of the elements that make our sites unique were being discussed in the war’s final year.

A question of headstones

One of the most iconic elements of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission is our headstones. While they vary from location to location, our headstones are generally universal and have come to symbolise the struggle and sacrifice of the World Wars.

In 1918, however, their look and feel were very much up for discussion.

Meeting minutes from 1 May 1918 show the Headstone Committee and Principal Architects were still very much debating how Commission headstones would look. Talking points were:

- Width of burial plots and stones

- Carving depth for inscriptions and sculptural elements (badge caps etc.)

- Carving and inscription process

- Headstone material

Horticulture progress

Image: A nursery at Heilly, France. Such locations were set up to specifically provide plant life and greenery to Commission cemeteries and memorials.

Did you know that the Commission’s horticultural and gardening teams were hard at work even as the battlefields of the Great War were shifting and moving?

A May 1918 report shows the development of our horticultural standards during this time. Highlights include attachments of horticulturists and gardeners to the DGRE in France and the UK, establishment of nurseries, and an update on the work of 1917 in seeding annuals and hardy plants for nascent cemeteries.

While much had been done to lay the shrubbery, flowers, trees, and beautiful blooms that spring up in our cemeteries and memorials, 1918 was still a year of war. One interesting aspect of the horticulture update is, once more, we see advancing armies affecting the work of the IWGC.

The report states:

“Prior to the German advance in March 1918, horticultural work, both in the cemeteries and nurseries, was in a very satisfactory condition and showed great promise for future development.

“Now, unfortunately, much of this work has been undone. The nurseries at Dernancourt and Merville are either in enemy hands or probably quite destroyed; while that at Varennes is too near the seat of active operations to be properly cared for and there is at present no one in charge.

“Of the cemeteries planted with hedges and roses bushes in the Somme back area, a great number are now in enemy hands and doubtless much of our work has been destroyed. Similar destruction must also have taken place in many cemeteries where careful gardening work had been done in the Merville area”.

Later on in the year, the areas lost to the advancing German army were recaptured and work could begin again.

Environmental hazards and conditions continue to provide challenges to our horticulture teams worldwide – although thankfully many are not located on active battlefields!

Now, our challenges are more around sustainability and global warming, but this 1918 report only goes to show how difficult conditions can have a major impact on our work.

1918: A pivotal year for the Imperial War Graves Commission

Just from the above, 1918 was a very busy year for the young War Graves Commission.

The work undertaken by Sir Fabian Ware, the principal architects, and the members of staff at the beginning laid the foundations for the Commonwealth War Graves Commission we know today.

Visit our archives to learn more about Commonwealth War Graves history

The Commonwealth War Graves Commission Archive collects manages and preserves materials documenting the history of the CWGC, the individuals we commemorate, the cemeteries and memorials we maintain, and to make such records accessible to the public.

Visit the archive in person at our Maidenhead head office or head online to discover our digitised documents and collections.

What will your search uncover?