27 September 2019

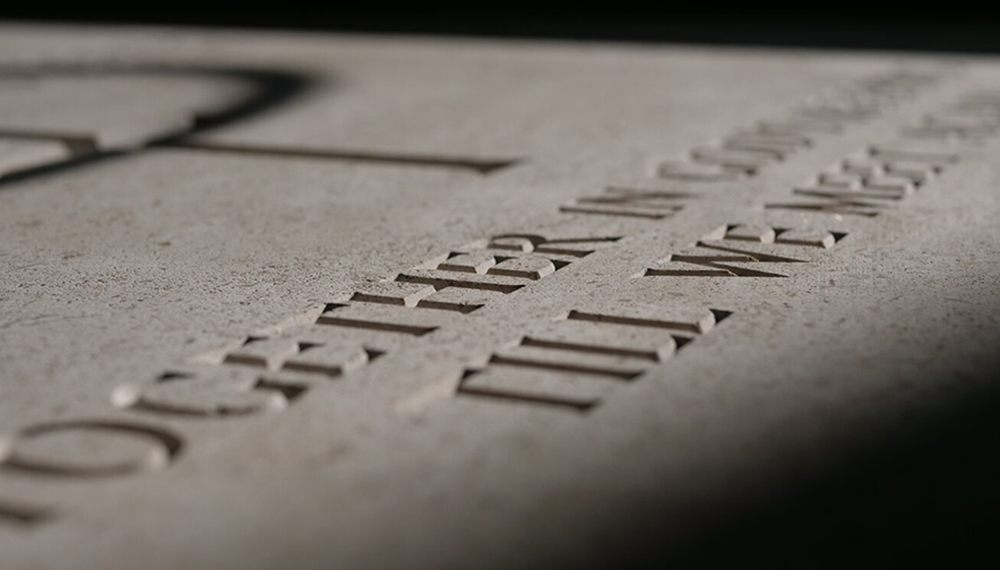

Written in Stone: Exploring different CWGC headstones

Standing in one of the Commission’s beautiful cemeteries it would be easy to view the rows of identically shaped headstones as uniform and regimented. That is partly the impression that they are intended to provide – reflecting the military comradeship these individuals shared in life, that continues in death. But look more closely and a different story is revealed. Mel Donnelly, CWGC's Commemorations Case Manager, explores how each element engraved on the stone tells us about the individual, no more so than their epitaphs.

As CWGC’s Commemorations Policy Manager I make sure that the causalities that we care for are correctly commemorated. I find it difficult to visualise the scale of the task faced by our predecessors. Hundreds of thousands of headstones had to be engraved by hand and installed in thousands of cemeteries all across the world. Grieving families were travelling on personal pilgrimages to visit the grave of their loved one, which meant there was an urgency to the work. The solution was a design that blended uniformity with individuality.

The working language of the Commission is English, reflecting the first language of the military forces and the majority of those who died. Therefore, military details are laid out in a standard format and engraved in English, with the exception of French speaking Canadians whose details may be engraved in French.

Whilst the men and women we commemorate died in the service of their country, they were also individuals whose story is reflected in the personal elements of their grave marker. The personal inscription gave their family an opportunity to speak to their loved one, and to us, in their own way and often in their own language. Today most headstones are produced by a special machine, but the Commission’s skilled stonemasons can also engrave details by hand, and we can include symbols and characters not found in a Latin or Roman alphabet.

Both world wars were truly global. Look more closely at many of our CWGC headstones and you will see the breadth of the languages spoken by those whose graves we care for today. They came from around the world, sometimes serving a Commonwealth country which was their adopted home.

Here are just a handful of examples I’ve chosen to highlight this diversity.

1. Danish

A headstone can show the origin of the family as well as the nation for whom they fought.

Private Count Ove Krag-Juel-Vind-Frijs served in Belgium with the Canadian Infantry during the First World War but his parents in Denmark elected to have his inscription engraved in their language.

2. Dutch

Private George Coetser of the South African Infantry died of influenza shortly before the end of the First World War.

His family chose an inscription in Dutch that confirms the bond between them would not be broken by death.

3. Afrikaans

The parents of Private H B J Botha from the Transvaal in South Africa captured their response to his death in Afrikaans.

4. Welsh

A native Welshman from Carmarthenshire, Private Hywel Griffiths was captured at Singapore and died in July 1943.

His inscription is the Welsh translation of a verse from the King James bible, and is cast in the bronze plaque which marks his grave in Myanmar.

5. Hungarian

Czechoslovakian born Private Bertrum Sabados died serving with the South Saskatchewan Regiment in July 1944 in Normandy.

His parents in Canada chose a quote about the nature of their loss to be engraved in Hungarian.

6. Religious Texts

Different religious beliefs are recognised in epitaphs engraved in a variety of different languages. The headstone of Sepoy Sikandar Khan of 82nd Punjabis praises the kind and merciful Almighty Allah.

Headstones for Sikh and Hindu servicemen include religious texts which reflect that they have been cremated according to their faith.

7. Cyrillic

Captain Prince Dimitri Galitzine died in 1944 during the liberation of the Netherlands serving with the Monmouthshire Regiment. His parents were originally from Russia and so the bible verse chosen for his inscription is engraved in Cyrillic lettering.

8. Chinese

Grave markers to members of the Chinese Labour Corps incorporate one of four epitaphs which are frequently used for Chinese soldiers. Engraved with an English translation, in Chinese they also reveal the area where the man came from: "Faithful unto death (至死忠誠 zhì sǐ zhōngchéng)", "A good reputation endures forever (流芳百世 liúfāng bǎishì)", "A noble duty bravely done (勇往直前 yǒngwǎng zhíqián)", and "Though dead he still liveth (雖死猶生 suī sǐ yóu shēng)".

9. Hebrew

Private Marcus Leslie Marks died serving with the Australian Army Medical Corps. He is commemorated on a Special Memorial in Tyne Cot Cemetery with an epitaph in Hebrew chosen by his father, which records the Jewish version of his name, military unit and date of death. 1917 equates to the year 5677 in the Jewish calendar.

10. Music

Language can be more than words – his love of music is captured as a bar of musical notes in the personal inscription of Second Lieutenant Hugh Gordon Langton in Poelcapelle British Cemetery.

11. Cree

John Chookomolin, who served as Private Jakomolin, is buried in Englefield Green Cemetery in Surrey. A First Nation Canadian, his inscription engraved in Cree symbols explains that he had left his wife and daughter in Nahmehkoo Seepee (Trout River) to fight in the war.

12. Bakwena

Some inscriptions have no direct translation. Private Simon Matsepe of the Bakwena people in South Africa died in Italy in1945. His widow chose a praise traditionally used during the ceremonies to mark the death of a clan member. It can only be understood fully by them and incorporates references to their totem animal, in this case a crocodile.

I find the choices that the families made deeply moving. Sometimes the words are simple and straightforward but other phrases are so personal the real meaning is known only to those who wrote them. Each and every headstone tells us something of the person who's grave it marks.