Caring for Our Sites

Our estate covers 23,000 locations in over 150 countries and territories, so the sun never sets on our work. We have over 2,000 ‘constructed’ war cemeteries (the largest being Tyne Cot in Belgium, the smallest Ocracoke Island (British) cemetery, USA).

Conserving our heritage estate

The term heritage estate covers our ‘built’ heritage, the memorials, the cemeteries with their Stone of Remembrance, Cross of Sacrifice, shelters, walls, plaques and the 1.1 million headstones commemorating the fallen from both World Wars.

Heritage estate also covers all the horticulture too and we are looking at the cemeteries, monuments and all the gardens and landscape together. We are taking a conservation-based approach to how we look after these into the new century.

The challenge, the change

Our worldwide heritage estate is aging, with parts of it over 100 years old, and in some cases this aging has been accelerated with changing weather patterns and pollution, so renovation and refurbishment is a constant and evolving process for us.

Our work programme is dictated by a cycle of inspections with any necessary remedial work performed by our own in-house specialists or in the case of larger projects, outsourced to approved construction companies with experience in building conservation.

Restoring the statues on the Chatham Naval Memorial.

Our policies have become more targeted, striking a balance between the effects of aging, caring for the environment and materials used to ensure the longevity of our estate.

Masonry work on the Cross of Sacrifice, Calgary (Burnsland) Cemetery, Alberta, Canada.

Original materials are preferred, however, over time, certain materials have become unavailable or unacceptable today and need to be replaced. For instance, we have moved away from concrete for repairs in favour of lime mortar and we prefer to repair rather than replace unless absolutely necessary.

Restoring the Askari 'Iron Men', Mombasa, Kenya.

RIGHT FROM THE BEGINNING OUR HEADSTONES HAVE ALWAYS BEEN A MIXTURE OF STONE TYPES INCLUDING PORTLAND STONE

One aspect that has evolved is the cleaning of our headstones. In the early days of the IWGC, a twelve-year cleaning cycle was the norm, with preservatives being introduced during the 1940s and chemical/biocide treatments in the 1970’s. This has given rise to the expectation of our headstones being a pristine white which was not the case in the early years of the organisation. In some cases, the treatments accelerate damage or deterioration to the stone, and leach chemicals into the ground.

See how we care for our headstones

Our headstones have always been a mixture of stone types depending on the environment they were to be placed into, with 30 stone types of differing colours and shade in our catalogue, each rated on their resistance to weathering, pollution and local soil type.

A selection of stone types found in our catalogue showing the styles and variations in colour.

We have 30 different stone types for our headstones SELECTED to withstand whatever environment they are placed in

We are currently moving towards a process of enzyme cleaning, which is better for both the environment and the stone, with cleaning only undertaken when necessary, reducing surface wear and water use. We are also adopting a high temperature/low pressure cleaning process compared to past high-pressure washes.

On our bronze plaques found in the Far East, we have moved away from using paint and lacquers to a traditional wax for rebronzing, which is more environmentally friendly.

The new rebronzing process at CWGC Kanchanaburi War Cemetery, Thailand.

Climate and conflict

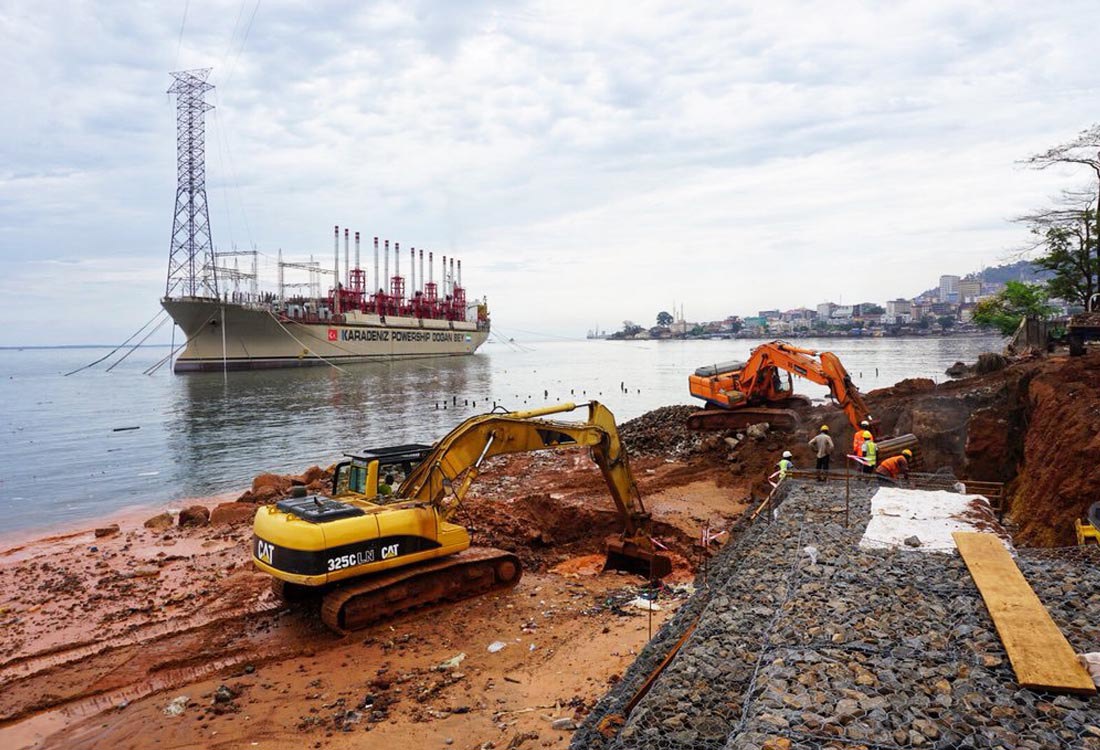

Damage from climate change is becoming increasingly prevalent as we experience more extreme weather events across our estate. For example, at King Tom Cemetery in Freetown, Sierra Leone, flash flooding destroyed its sea wall in September 2015. Partnering with a local contractor, we had to stabilise the sea front and build a brand new, more robust sea defence, one of our most complicated engineering project.

View of the damage to King Tom Cemetery after the flash flooding.

Close up of the damage, giving an indication of the force that hit the sea wall.

The newly completed and redesigned defences.

Repairing the damage from conflict zones is a considerable challenge also, sometimes having to make areas safe from unexploded ordnance before we can start on any remedial work. Gaza War Cemetery is a case in point with damage often caused by shelling.

Some examples of the challenges facing the CWGC staff in Gaza.

An extreme example of what CWGC can face was the Basra Memorial moved from the Shatt al-Arab channel into the desert during the Saddam Hussein era, causing damage to the structure and commemorative panels. The remedial work had to be postponed until the political/military situation improved to allow us to assess the most appropriate way of ensuring that the names are commemorated in country.

The Basra memorial in its new desert location, moved in the 1990s by the Saddam Hussein regime.

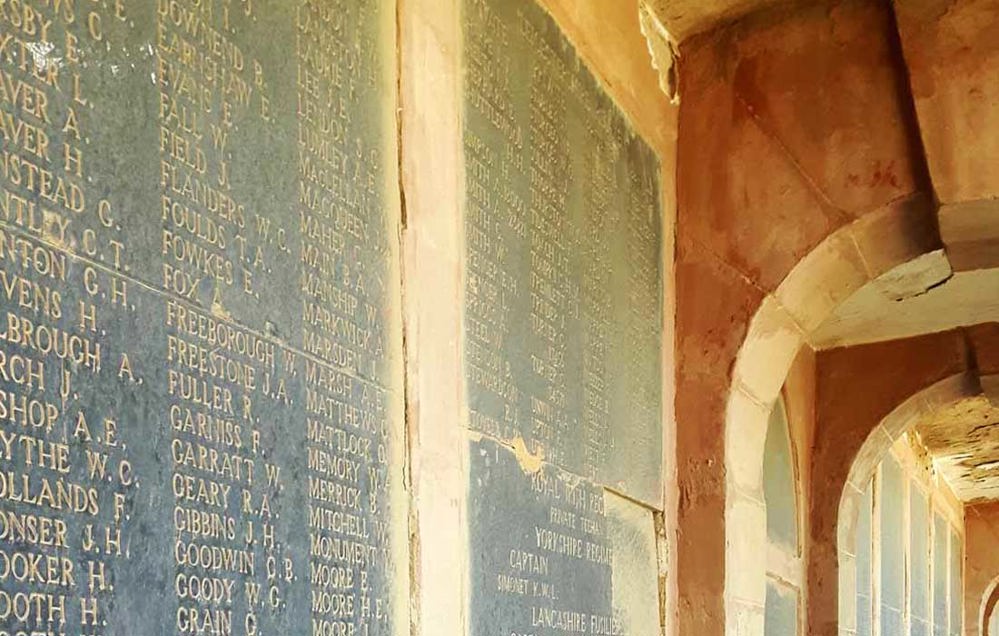

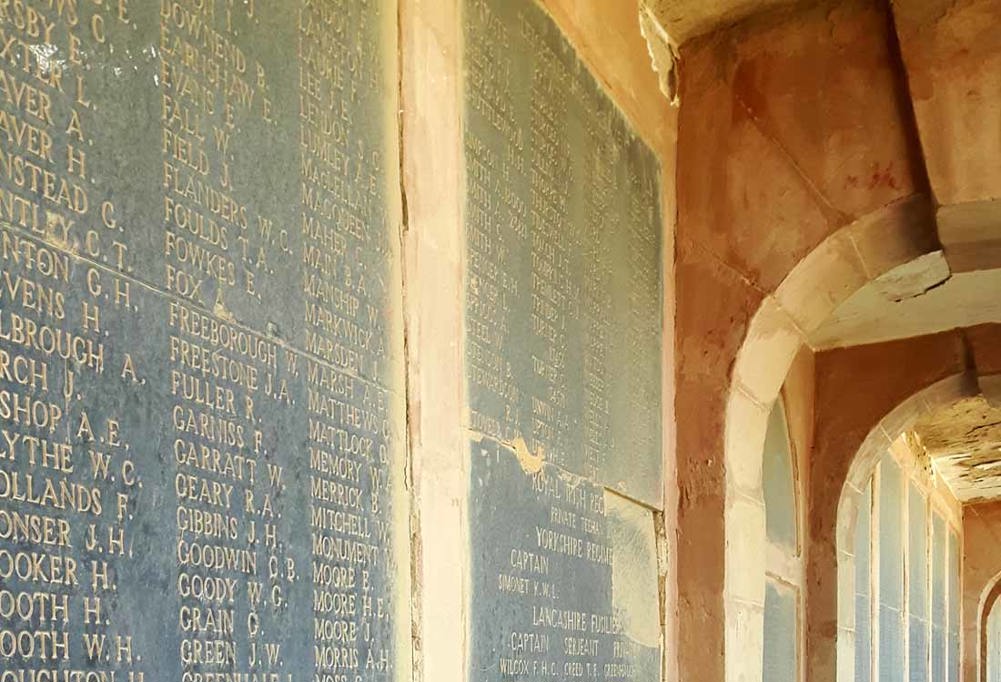

The damage to the panels caused during the moving of the Basra Memorial.

READ OUR CONSERVATON POLICY

Our Conservation Policies reflect our aim to manage change whilst sustainably caring for our sites.

To the Four Corners...

Read about some of the many projects we have undertaken and challenges we regularly face around the world.

Race against the sunset

Ascension Island

Location: Georgetown, Ascension Island Language: English Altitude: 1m Rainfall: 142mm

Temperature: 20°c - 28°c Biggest challenge: Isolated island location

A thousand miles from the nearest mainland, in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean, sits an island airbase. There’s not much there beyond an airstrip, a weather station and a NASA telescope that combs the skies.

But nestled on the windy shores of Ascension Island is also one of the world’s most isolated island war cemeteries.

On his last visit, regional manager Simon Fletcher had only hours of daylight to rush across the island before his return flight.

Ascension Island cemetery contains seven Commonwealth war graves. Some were buried when their ship passed through, others were stationed here. One was a South African labourer. Another, a telegraph operator from South Shields, UK.

Today, civilians can only reach the island via St Helena – a full 800 miles to the south – on the monthly flight that links the two.

In remote outposts like this we rely heavily on the support of those stationed there.

CWGC’s area manager Simon Fletcher recently took the long journey to check the condition of the war graves on both islands and re-establish local connections.

“It was a race against the sunset as soon as we landed in Ascension,” he said. Within hours, he had to be back on the same plane or risk being stranded for a month.

“I only had about an hour of daylight to rush to the small war cemetery and see what condition the war graves were in before rushing back to the airstrip to get home.”

Thankfully all was well. He returned safe in the knowledge those seven men, however far from home they may be, were still lying in peace in a clean, well-tended site, thanks to the generosity of the RAF personnel stationed there.

It contains seven Commonwealth war graves. Some were buried when their ship passed through, others were stationed here. One was a South African labourer. Another, a telegraph operator from South Shields, UK.

Today, civilians can only reach the island via St Helena – a full 800 miles to the south – on the monthly flight that links the two.

The war graves in St Paul's Church, St Helena stand on the slopes high up the island.

On St Helena, he checked for another 14 war graves. This time maintained by the friendly team who tend the sloping churchyard of St Paul’s Cathedral on our behalf.

It contains seven Commonwealth war graves. Some were buried when their ship passed through, others were stationed here. One was a South African labourer. Another, a telegraph operator from South Shields, UK.

Today, civilians can only reach the island via St Helena – a full 800 miles to the south – on the monthly flight that links the two.

Even in St Helena, CWGC finds people ready and willing to help us in our work.

Aside from periodic inspections like Simon’s, the only practical way to maintain remote sites like these are through strong local relationships.

“Even in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean, we find people who are willing to help us remember those who died.”

In the distance behind the graveyard is a narrow runway where the monthly plane that links Ascension Island takes off.

RESTORING THE 'IRON MEN'

THE ASKARI WAR MEMORIALS

Location: Mombasa, Kenya Language: English / Swahili Altitude: 21m Rainfall: 999mm

Temperature: 22°c - 33°c Biggest challenge: Restoring detailed statues without blueprints

Some of the first and last shots of the First World War were fired in Africa. Hundreds of thousands of men from across the continent were mobilised by European powers on both sides and drawn into long and bloody conflict.

These stories are often overshadowed by tales from the Western Front.

But the Commonwealth War Graves Commission’s commitment to Africa is huge. It spans 43 countries. It’s also the site of some unique memorials that, when unpicked, tell the nuanced task of remembrance on this vast continent.

In 2017 the appearance of 3D scanners in the centre of Mombasa drew crowds of curious locals as the CWGC began restoration of one of these war memorials.

The Mombasa African Memorial – one of four to be built and the first to be restored – was unveiled in 1927. It features four tall bronze men – each representing the unique make-up of the forces who served; a vivid reminder of the Africans who died under the banner of the British Empire.

A young boy looks up at the Dar Es Salaam African Memorial in this photo from the CWGC archive.

Along with similar statues in Nairobi, Dar Es Salaam and Abuja, these are the only places in the world where you will see something so lifelike at a Commission site.

They were created out of necessity.

By the time the Commission was able to gain access to East Africa and begin the difficult work of locating the First World War dead, there was little to no information available about the majority of Africans who had served, including accurate death tolls or burial locations or even their names.

The Dar Es Salaam African Memorial will be the latest to be restored thanks to 3D scanning technology.

Panels on the Dar Es Salaam African Memorial.

Telling more of the story of those commemorated.

Without definitive proof of where, or even how many people had died, the model being drafted in Western Europe – giving every person a name on a headstone above a known grave or a war memorial to the missing – would never be possible. Instead, something else was needed.

After much soul-searching, the Commission settled on bronze statues. Each one is unique, but similar in form and evokes a real sense of those being commemorated.

So much so that a mother in Mombasa was adamant that it was her boy who stood up on the pedestal and he had been transformed into “an iron man who could neither talk to her nor see her”.

Posed photographs were commissioned to allow sculptor James Stephenson to make each sculpture as lifelike as possible.

3D scanning, combined with careful studies of original photographs allowed CWGC to meticulously restore every detail.

To achieve this, sculptor James Stevenson studied specially commissioned photos of servicemen from various regions to capture their likeness. Great attention to detail was paid, right down to the clothing, weapons and equipment each would have had; be they an Intelligence Corps scout or an Arab rifleman.

Such was the care, that restoration of these statues – which had no original designs or blueprints – posed a challenge. 3D scanning and careful comparisons of original photographs allowed damage and deterioration to be put right to within a millimetre.

The detailed parts of these statues were replaced with millimetre precision thanks to the 3D scans.

And today, thanks to state-of-the-art technology, these striking memorials keep telling the story of those nameless men, for the next century.

Friends in remote places

Baro WAR CEMETERY

Location: Baro, Nigeria Language: English Altitude: 57m Rainfall: 1,331mm

Temperature: 19°c - 41°c Biggest challenge: Remote, isolated headstones

When it comes to Remembrance Day, and you bow your head in silence, you could be forgiven for not knowing about the village chief who helps make our work possible.

But in Nigeria, it’s just another part of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission’s work.

Across the vast West African nation are a series of isolated headstones, mostly men who died of illness while stationed here in the First World War.

Without local help, it's almost impossible to locate the remote war graves at Baro Cemetery.

Throughout the world, we rely on making strong relationships with those whose land our war graves lie in.

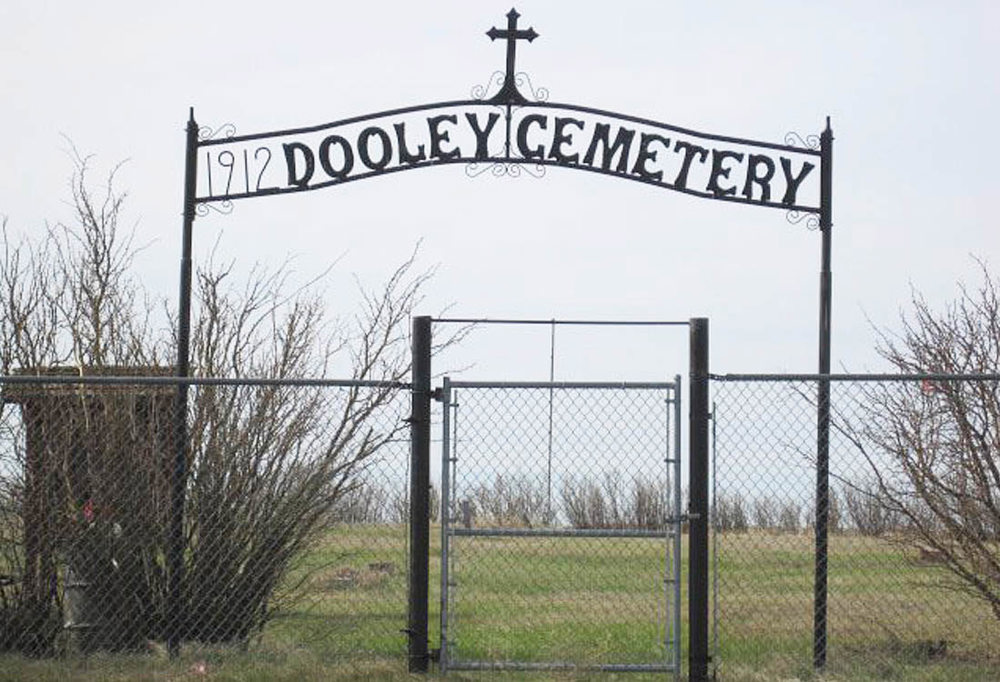

In England, that often means vicars. In Canada, that can be farmers out in the prairie.

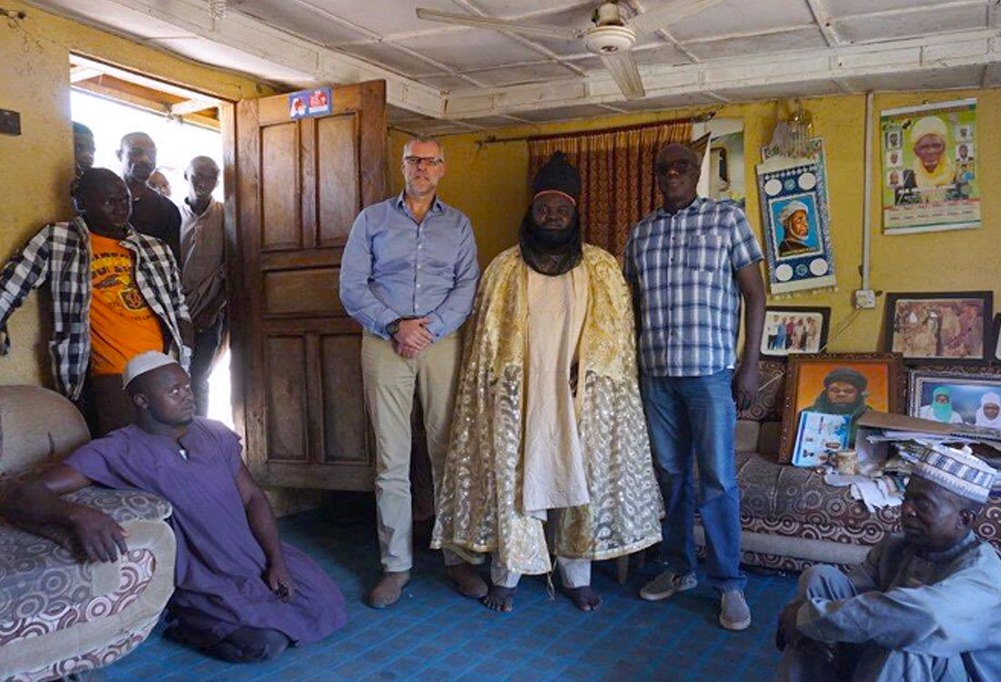

In West Africa, that means building a relationship with village chiefs, like here in Baro Village with Alhaji Mohammed.

It's customary to meet with the Baro Village Chief, here joined by Simon (left) and Lolu (right) of CWGC.

Lolu Enabolu, CWGC’s Nigerian supervisor, helps us to build and maintain these vital connections on the ground. On his last visit to Baro with regional manager Simon Fletcher, the pair sat down for the customary tea and conversation with Alhaji, before being led to the war graves. Small formalities like this go a long way to gaining local trust.

In these remote locations, you can never underestimate the importance of local trust.

Here at Baro War Cemetery, CWGC cares for the graves of two First World War soldiers.

Another lone burial, that of Captain Haworth Massy, in Udi village, bears a powerful reminder of how World War history unites the world.

Captain Massy, whose war grave is seen below with Lolu on his latest inspection, may appear to be buried in isolation in this quiet spot, a day’s drive south of the Nigerian capital, Abuja.

But you can draw a line, 3,000 miles long, from this place to one of CWGC’s most visited locations – the Menin Gate, upon which is engraved his brother’s name.

The two signed up for the same war. Though they died in very different ways, and at opposite ends of the world, the memory of their family’s loss is preserved forever by our global task.

A job that we can only do by building strong local connections everywhere we go, whether it’s the vicar, the farmer, or the village chief – something worth trying to remember next 11 November.

Buried in Udi village is Cpt Massy, whose brother, Pte Massy is remembered on the Menin Gate.

Cautious return to Iraq

BASRA WAR MEMORIAL

Location: Habbaniya, Iraq Language: Arabic/Kurdish Altitude: 50m Rainfall: 133mm

Temperature: 8°c - 44°c Biggest challenge: Security concerns

The challenge CWGC faces in Iraq is huge – it’s the equivalent of building a new Tyne Cot Memorial in the middle of the desert in a country where safe access can’t always be guaranteed. And that’s just looking at solving one of the 19 locations in the country we’re responsible for.

Most have been damaged or deteriorated due to recent conflicts. Sadly, Iraq is no stranger to war. During the First World War, then known as Mesopotamia, it was the scene of the Empire’s largest operations outside of Europe and saw its worst defeat at the Siege of Kut.

Today Iraqis live with the fallout of more recent upheavals. The Commission has had to stop and start here on many occasions. In 1990 we formally withdrew. It was simply unsafe.

In our absence, many sites have deteriorated. The soil in the region has such high levels of salt that, without preventative work, it seeps into headstones making them so brittle they can be virtually crumbled by hand.

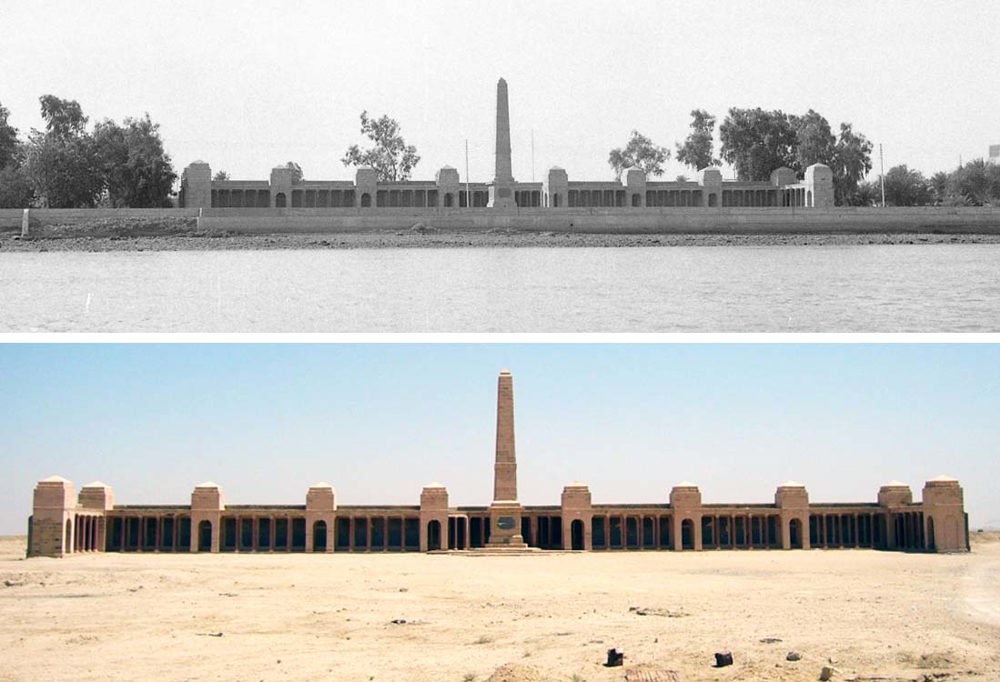

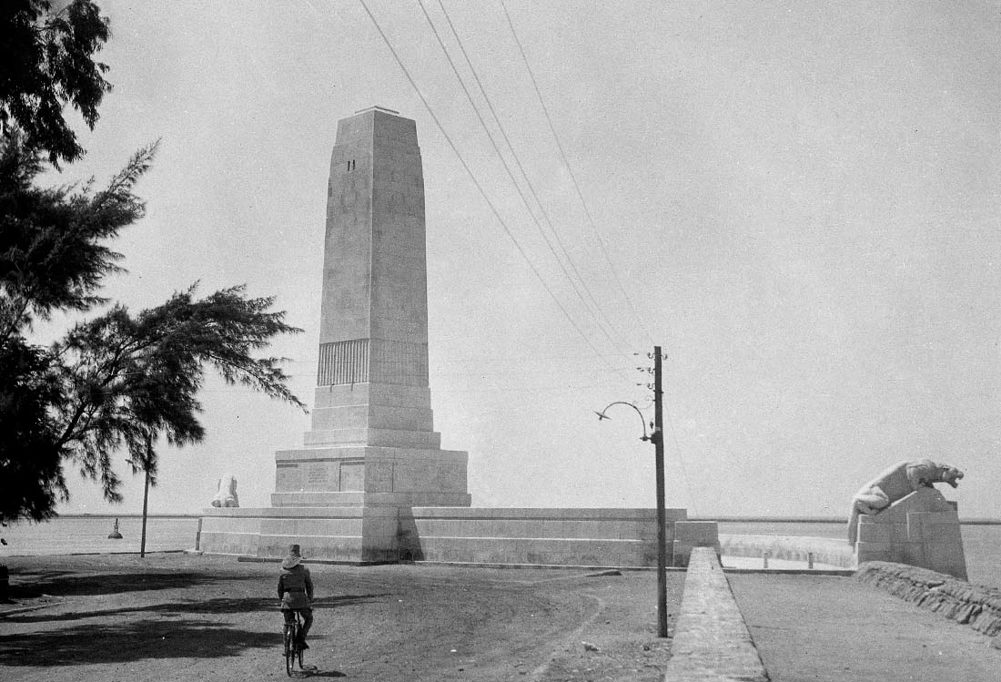

The Basra Memorial on its original site (above) and new site (below).

The largest memorial in the country is the Basra War Memorial. It originally stood at the side of the Shatt al-Arab River on the edge of the city but was moved in the late 1990s by Saddam Hussein’s regime into the desert.

After decades without regular maintenance, the war memorial is showing signs of age. However, it’s not just repair works that are needed here – it’s missing 30,000 names, too, the equivalent of the Tyne Cot Memorial.

Damage to the name panels and structure on the Basra Memorial.

When first unveiled in 1929 the names of most of the men of the Indian Army who it commemorates were not accurate. War records at the time hadn’t been properly compiled and the Commission could only be provided with the names of Indian officers, and British officers and men.

Since then an accurate list of the names has since been compiled and all lie in the CWGC’s Iraq Roll of Honour, on display in the UK, waiting for a time when conditions on the ground allow a more permanent solution.

However, there is hope. Step by step, progress is being made in Iraq. In 2012, during a gap in hostilities, Kut War Cemetery was completely renovated. Before and after images are a testament to success. In 2019, the most recent project has also succeeded.

Renovation work begins at Habbaniya War Cemetery.

View of the renovated cemetery with nearly 300 brand-new headstones installed by CWGC.

Within the walls of Habbaniya, a former RAF base that’s now operated by the Iraqi Army, the war cemetery was in almost complete disrepair. Now, nearly 300 brand new headstones have been installed and the entire site renovated, only made possible by finding a trusted local contractor.

The Commission has to play the long game at times. When your task lasts forever, you never know what progress the future might bring.

CWGC staff pay their respects on an inspection trip to assess the condition of the Basra Memorial in 2017.

THE UK's 'MOST REMOTE' WAR GRAVE

BEN MORE ASSYNT

Location: Ben More Assynt, Scotland Language: English Altitude: 655m Rainfall: 974mm

Temperature: -2°c - 17°c Biggest challenge: Remote locations

Nowhere else in the UK is the challenge of access to war graves more obvious than in the Scottish Highlands and islands.

CWGC’s Scotland team often combine their commute with ferries and planes as they seek out isolated graveyards, far from the mainland. A bicycle can be an essential piece of kit when arriving on an island without cars to inspect remote headstones.

Remote islands like St Finan's Isle provide an extra challenge for our regular maintenance cycles.

The war dead they look after, include islanders who served and returned, only to die of injury or illness. Many are pilots or seamen who died in accidents or whose bodies were washed ashore, far from home.

Maintenance trips are constantly rescheduled around narrow weather windows when it’s unsafe to land on small remote islands, like Fair Isle, where just a handful of war graves lie.

These beautiful locations can only be reached in narrow weather windows.

The Commission’s traditional Portland stone will hardly be found here. Granite is one of the few substances that stands a chance of surviving the climate.

The challenge isn’t new – archive documents from 1945 show one former employee’s concerns that the vast spread was too much to handle.

His preferred solution: an island-hopping gardener, equipped with a motorbike and a lawnmower in a sidecar.

The difficulties in Scotland come high up in the mountains too.

Three miles from the nearest road and more than two thousand feet above the nearest village, lies the isolated war grave of six airmen.

They are buried on a rocky plateau near the summit of Ben More Assynt, 20 miles northeast of Ullapool.

The old pile of stones marking the graves can be seen behind the disintegrating wreckage.

All of them died in April 1941 after their plane crashed. When their bodies were later found by a local shepherd, he buried them together using parts of their destroyed plane for a makeshift cross.

By 1944 the Commission had arranged for a temporary war memorial cairn to be erected above the graves. It was unthinkable at the time to install anything more permanent in such a place.

The original Imperial War Graves Commission marker seen at the site of the crash.

To give families somewhere to mourn, a special war memorial was placed by the Commission in the nearest village of Inchnadamph. A slowly growing pile of stones, added to by the odd passing walker, was all that remained up on the high mountain slopes.

And that would have been where the story ended.

Until 2010, when a local mountain guide approached us. He had heard concerns the exact location of the crash site could get lost to time.

And so, with the help of the MOD, a 600kg special CWGC granite marker was lowered into place by helicopter – possibly the most remote war grave in all of the UK.

The 600kg special grave marker was lowered into place in 2010 thanks to the support of the MOD.

The more permanent marker was installed to ensure the location of these graves is never forgotten.

Our one man in Ireland

Colmcille's Graveyard

Location: County Kilkenny, Ireland Language: English / Irish Altitude: 34m Rainfall: 879mm

Temperature: -3°c - 21°c Biggest challenge: War graves in disused churchyards

Ireland is a delicate place to work for an organisation that calls on people to look back on their history.

Even just half a generation ago, we would not have received the strength of goodwill that we do today. On our new regional manager’s first weekend in post, he was invited to a Remembrance Sunday commemoration ceremony at Glasnevin War Cemetery in Dublin.

There he heard a poignant and powerful speech by the President of the Irish Republic Michael D. Higgins calling for all victims of the World Wars to be commemorated and remembered.

As with elsewhere, the work at hand here is about preserving a slice of heritage and allowing simple acts of individual remembrance.

Our commitment here is sparse but no less important for it. Around a fifth of the war graves in the Republic of Ireland alone are on the grounds of churches which have since closed, become heritage sites or have found alternative use.

The flooded entrance to Colmcille's Graveyard and weathering to the civilian headstones typical of disused churchyards containing war graves.

Some, like Colmcille’s Graveyard in County Kilkenny, are over a kilometre away from the nearest road. The only access takes you through muddy tracks and horse fields, making any visit feel like a voyage of discovery.

The day-to-day maintenance in the Republic of Ireland is done on the Commission’s behalf by the Office of Public Works with whom we have been in partnership with for many decades. Without the need for gardening staff, we have only one employee permanently based there.

It’s Malcolm Ross’s job to inspect the work and, more importantly, maintain and build the hundreds of local relationships that have kept our 5,500 war graves in order, across more than 1,000 locations.

Rural war graves such as these in Dugort, County Mayo, often boast dramatic backdrops.

“If the topic comes up when I meet someone new, I make it clear I’m not here to talk politics or religion, we have one job to do and I always open conversations with the simple task at hand.”

Malcolm then needs to deal with the sheer variety that comes from being our one man on the island.

“One day I can be hiking around muddy fields, talking to farmers and trying to find a remote headstone in rural Offaly, the next I’m at a black-tie reception in central Dublin greeting ambassadors and defence attaches.”

A single First World War headstone stands among civilian graves in Kilcommock Old Graveyard.

Reaching the long-abandoned Colmcille’s Graveyard is typical of the rural spots where you can find war graves and war cemeteries here.

There are civilian graves, many showing the family names of the local village, which can be centuries old, carved in distinctive local stone. And among them, mostly made of Irish Blue limestone, are the war graves, our permanent reminders of the war dead.

The history and politics of who and how they fought may remain a delicate matter, but their names are far from forgotten.

Ruins in the grounds of Rathcooney Cemetery, County Kerry, show where the church once stood.

An Oasis of calm

Gaza WAR CEMETERY

Location: Gaza City Language: Arabic Altitude: 39m Rainfall: 148mm

Temperature: 9°c - 36°c Biggest challenge: Missile strikes and power cuts

Despite missile strikes, power cuts and make do and mend machinery – CWGC’s war cemeteries in the Gaza Strip remain carefully tended oases of calm.

The region’s instability spills onto the global news on a weekly basis, impacting the daily lives of those who live and work there. But the Commission isn’t in the game of politics. We’re gardeners and guardians of heritage.

Many times in the history of Gaza War Cemetery, the site has been caught in the crossfire.

When chaos reigns outside the walls of our cemeteries here, the local team does as much as they can to maintain a sense of calm and normality within.

The setbacks they face are significant. Sometimes our sites get caught in the crossfire. Gaza War Cemetery has been hit three times in the last decade alone; on one occasion nearly 300 headstones were damaged.

On one occasion, nearly 300 headstones were destroyed by a stray missile.

A former gardener used to talk of once chasing armed militants away with his broom. Today, we insist staff look after themselves first. But even when things are calmer they face continual issues.

The Gaza Strip suffers from major water and electricity shortages – a big problem when your job is maintaining a garden cemetery. The last time petrol ran out, staff modified machinery to run on gas.

Just getting equipment through the tight border controls can be a problem. Something as simple as a replacement lawnmower can take months, sometimes years, to arrive.

Once it's safe to return, staff are quick to clean up and begin repairs.

In spite of all of this, our dedicated and resourceful team continue to do the Commission proud. On top of the impressive standards, the war cemeteries are used as a teaching spaces too.

In an area where conflict and loss are all too fresh in people’s minds, team member Ibrahim Jaradah – the fourth generation of his family to work for us – guides groups of local children, reminding them that every life lost, no matter the cause, is something that should be remembered.

He said: “Our responsibility is not easy. Our task is to preserve these cemeteries against many challenges. We feel the weight of expectations, but we also feel the importance of our work.”

Despite the difficulties our team in Gaza have created a real oasis of calm.

The problem of uninvited guests

Kariokor WAR CEMETERY

Location: Nairobi, Kenya Language: English / Swahili Altitude: 1,657m Rainfall: 1,062mm

Temperature: 12°c - 28°c Biggest challenge: Site encroachment

Upon arrival at Kariokor war cemetery, our staff know there is still work to be done before they even open the gates. They can hear the tell-tale sound of a hammer and nail.

This isn’t their colleagues at work, making repairs. The sound they’re hearing is someone nailing out a taut animal hide to dry, just metres away from a war grave.

A worker nails out animal hide within the grounds of CWGC's Kariokor Cemetery.

It’s one of a few businesses which have set up shop, without permission, in the war cemetery grounds in the Nairobi suburb named after the Carrier Corps of the First World War, many of whom were recruited from this neighbourhood.

Today, it’s where 59 African Second World War casualties are buried. Encroachment isn’t unique to Kenya. Around the world, as cities grow, many of the 23,000 locations at which we operate face challenges created by man-made expansion.

CWGC technical supervisor Daniel Achini speaks to those who have taken to using the cemetery for their tanning business.

At Kariokor, CWGC has been working carefully with local authorities to find the best long-term solution. One plan is to renovate the space into a memorial park, with more information to help people understand the history of the Africans buried there.

A key partner in helping to spread that story is the Museums of Kenya. Their interest in Nairobi (Kariokor) Cemetery saw them bestow it with their highest level of historical importance and ‘gazette’ the whole site as a heritage asset, a part of Kenya’s history as well as that of the Second World War.

CWGC archive photo of Kariokor Cemetery.

People trying to find space to set up their businesses aren’t the only uninvited visitors causing a problem for the Commission’s Kenya team.

Another unwanted guest in nearby Nairobi War Cemetery is something most European gardeners have probably never thought of protecting themselves against – monkeys.

“They come in and eat the plants,” said Daniel Achini, our senior technical supervisor out in Nairobi.

“The problem is that there is less food for them in the forest these days, so they come to the city looking for food. Our cemeteries are full of plants, lined up ready and waiting.”

The plants that survive the monkey invasions need constant care in order to survive the region’s occasional droughts. Guarding against unwanted visitors and reacting to changing weather patterns are all just a part of what it takes to make sure those who died on this soil aren’t forgotten.

“We know there’s still plenty of work to do,” said Daniel, “but, we’re on it.”

In Nairobi War Cemetery, monkeys often eat the plants, especially during the dry season when food is scarce.

CIVIL WAR TO CIVIL ENGINEERING

KING TOM WAR CEMETERY

Location: Freetown, Sierra Leone Language: English Altitude: 10m Rainfall: 2,945mm

Temperature: 23°c - 33°c Biggest challenge: Site at risk of collapsing into sea

“I spent most of Sunday morning lying on the floor of my room with the mattress propped against the window in case of flying glass. Throughout the morning there were repeated visits to the hotel from the rebel soldiers who shot at and robbed guests.”

This was the account of David Richardson, then a Commission horticulture manager, on a working visit to Freetown, Sierra Leone in 1997. Partway through his trip to oversee replanting and renovations at our war cemeteries, civil war broke out.

He and other foreign visitors were holed up in their hotel for days until UN planes were able to evacuate them.

Due to the sheer global scale of our work, world events occasionally impact us. Thankfully staff have never had as close a call as this since. The priority is always to ensure people’s safety. Stones and planting can be replaced. The long-term nature of our work allows us to bide our time when things become unsafe.

By the noughties a gradual return to Sierra Leone was possible.

Despite the forced absence, the main site in Freetown, King Tom Cemetery, was still in relatively good condition. Until a new threat emerged from the weather.

The old sea wall at King Tom Cemetery seen to be collapsing after flash flooding.

Record rainfall in 2016 saw a deluge of water hit the cemetery. The sea defences were destroyed and the site was at risk of collapsing into the ocean.

Against a backdrop of flooding and an outbreak of Ebola, we had to balance complex needs.

One option only considered in extreme circumstances, would have been to exhume the war dead away from the coast to higher ground.

But it would have been near impossible to get approval to dig up human remains during an epidemic, regardless of when they had died. Almost a quarter of the war dead buried in King Tom were killed by Spanish flu during the First World War. No one was going to question people’s nerves in the face of this new contagious disease – we had our own reminder of their costs.

“The mayor also told us the cemetery had become part of Freetown’s heritage. So we respected local wishes and stuck to an engineering solution,” said area director Rich Hills.

It took time, but an answer to the problem was found, as well as an excellent local partner to completely rebuild a brand new sea wall.

“It was one of the Commission’s most complicated engineering projects and we couldn’t have done it without local support. Making such a huge achievement in a country that we’d been evacuated from only a few decades earlier made it all the more poignant.”

The complicated rebuild begins.

The work went right up to the water's edge.

Preparing the metal baskets.

The rubble-filled baskets protect the ground above while dissipating the force of the waves.

King Tom's Cross of Sacrifice, now protected from collapse into the sea.

Workers celebrate the completion of the new sea defences in 2018.

The danger of wild boar

Kranji WAR CEMETERY

Location: Singapore Language: English, Malay, Mandarin Altitude: 23m Rainfall: 2,340mm

Temperature: 24°c - 33°c Biggest challenge: Wild boar, weather

Cracked headstones and torn-up turf, all courtesy of our least wanted guest in Singapore – wild boar.

The creatures prove a real problem for the Commonwealth War Graves Commission. The open land of Kranji War Cemetery, on the outskirts of the Asian city-state, is an appealing place for them.

The tell-tale signs of wild boar damage. When a wild boar is spotted, our cemetery must be evacuated.

For decades gardeners here have had to look out for boar and the damage they cause to the war cemetery they care for. More than 4,000 Second World War dead are buried here. Another 25,000 are named on a series of war memorials.

From high up on this vantage point, you can look out and see where the Japanese Army came from on that fateful February of 1942, during the Battle of Singapore.

Kranji War Cemetery's Cross of Sacrifice under construction after the Second World War.

Christopher Leong, our head gardener at Kranji, is all too familiar with the challenges of preserving this reminder of all those lost lives.

His team take seriously any sighting of wild boar, immediately evacuating the site.

Specialist fencing runs deep underground to prevent all but the most determined of invaders from getting through.

It’s not just animals that put pressure on this historic site. The weather plays its own part too, bringing trees down in the monsoon.

The grand Singapore Memorial, bearing more than 24,000 names, stands at the top of the cemetery.

The Singapore Memorial sits on the highest point of the hillside cemetery now. The iconic design pays tribute to the air force, navy and army – the wings of a plane, the fin of a submarine, and the rows of soldiers stood to attention.

Weathering has already taken its toll on the memorial. CWGC is restoring the structure, tearing off the old waterproof layer on its roof, and replacing it with more robust modern materials.

While the wild boar might be a dangerous visitor, the cemetery still draws in people wanting to pay their respects. Every year thousands turn out for the Remembrance Sunday service, just the kind of guests our founders had in mind, all those years ago.

All on their own

Neidpath WAR CEMETERY

Location: Saskatchewan, Canada Language: English Altitude: 749m Rainfall: 340mm

Temperature: -22°c - 27°c Biggest challenge: Huge geographic spread

In Canada, the Commission’s biggest issue is geography, simply put there’s an awful lot of it.

Covering all this ground to ensure every war grave remains in good condition is a time-consuming job. At times it calls for our local team to become intrepid explorers in their own country.

These remote locations contain some of the hundreds of isolated headstones the CWGC return to every year.

More than 1,700 locations – 60 per cent of our Canadian sites – contain just a single war grave. The long and cold Canadian winters mean that for more than half the year it’s not practical to reach them.

When the weather allows, a typical day can take in a dozen or more remote and abandoned war cemeteries in rural country. Staff check for access, the condition of the stone and that the name remains clear, before heading onto the next.

One of those is the war grave of Private Donald Pollock. He is buried next to his twin brother on the family’s isolated old farmstead, near the hamlet of Neidpath in Saskatchewan.

All around the world CWGC relies on local help to access remote war graves. Here, George Carlson often guides staff to this isolated headstone.

The pair died on the same day, 15 November 1918. Donald had returned from the First World War bringing Spanish flu to their remote home. As he was still serving at the time of his death, Donald is commemorated by CWGC. His brother Alexander, a civilian, is at his side under a private war memorial.

Finding this spot is only practical with the help of the current landowner. Hours of traipsing about with a GPS is replaced with a short ride on the back of his quad bike.

The final part of some visits often call for off-road transport, in this case, courtesy of the landowner.

Dominique Boulais, of CWGC’s Canada and Americas Area, described his last inspection of the site: “There was only one padded seat and it was for the driver; I sat on the steel grill facing the back and receiving all the mud flying from the rear wheels and breathing the fumes from the exhaust pipe. I made sure I kept my mouth shut during the fifteen-minute ride.” Once there, in a dip between folds in the land, are the headstones of the twin brothers.

“There wasn’t a single sound except the wind.”

Donald Pollock, buried on the right, lies next to his civilian brother. Both died of Spanish flu on the same day.

The effect on families like the Pollocks, to have their son returned home from the First World War, only to later die of illness or injury, would have been devastating. That human cost has left a legacy for CWGC that comes with challenges that remain to this day.

Across long distances the Commission continues to return to the homes of thousands of Canadian men like Private Pollock, one by one, making sure their sacrifice is remembered, for evermore.

One of the many remote markers CWGC cares for.

CROUCHING TIGER, HIDDEN NAMES

PORT TEWFIK WAR MEMORIAL

Location: Heliopolis, Egypt Language: Arabic Altitude: 61m Rainfall: 25mm

Temperature: 8°c - 39°c Biggest challenge: Memorial destroyed and inaccessible

For more than half a century two crouching stone tigers stood, ready to pounce, at the mouth of the Suez Canal.

Their wide-open mouths and bared teeth called on the thousands who passed by to look up and recall the memory of more than 3,000 Indians who gave their lives in Egypt and Palestine during the First World War and have no known war grave.

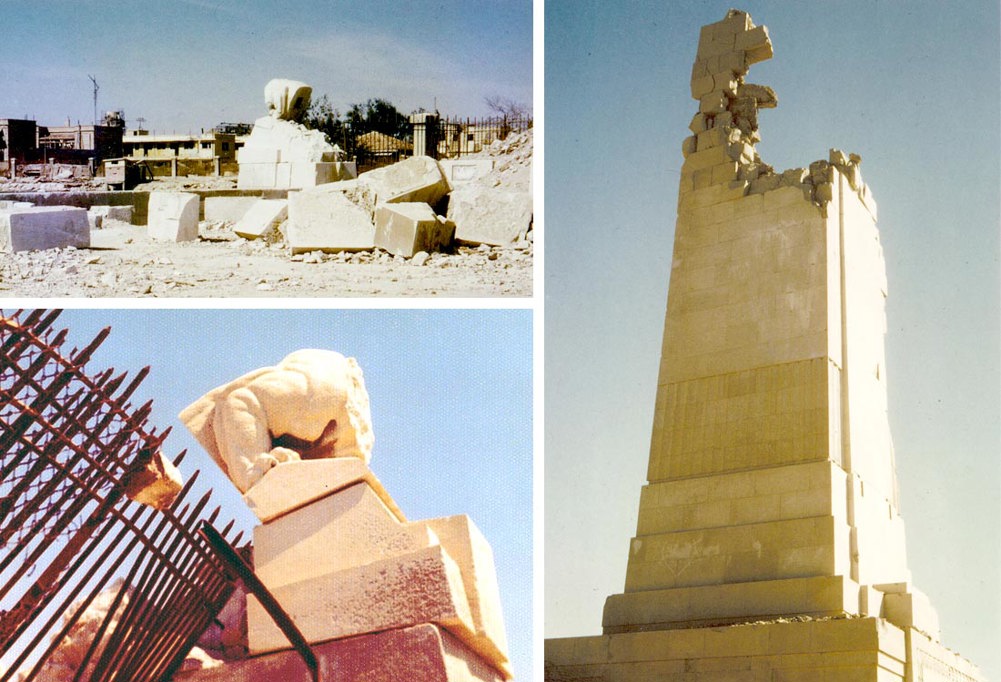

However, if you stood there today, you would never know. In the 1960s the sculpted tigers, along with the rest of the Port Tewfik War Memorial, were destroyed beyond repair. Many of the bronze panels were stolen. Collateral damage in the Arab-Israeli War.

It’s now one of a handful of CWGC sites that, in its original form, exists now only in photographs.

The original Port Tewfik Memorial overlooked the busy entrance to the Suez Canal.

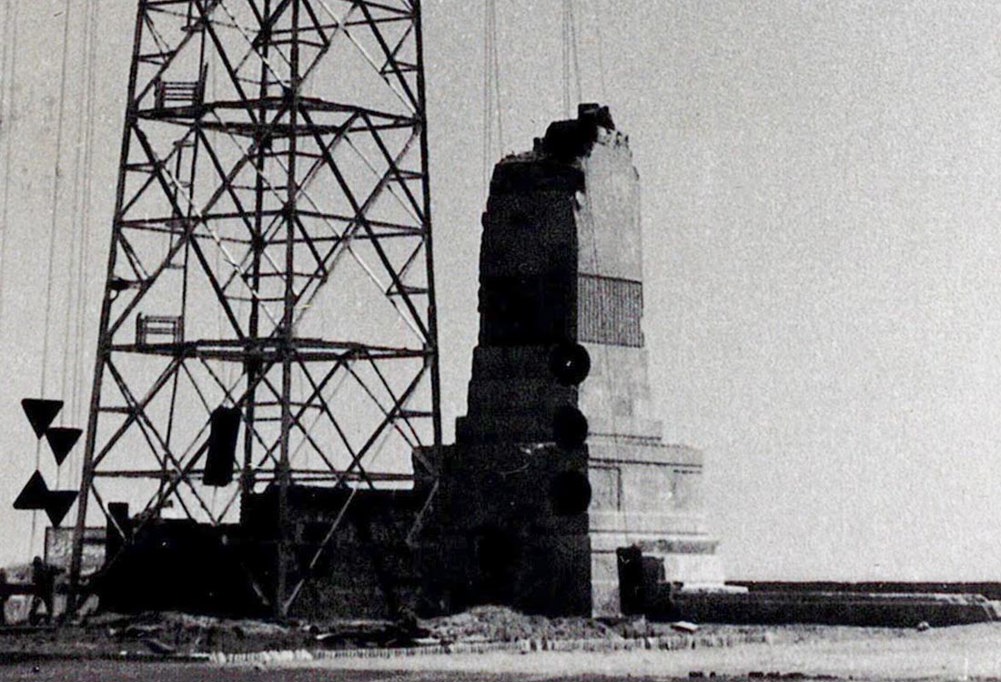

The Port Tewfik Memorial was caught in the crossfire of the 1967-73 Arab-Israeli War.

The damage to the crouching tigers and Memorial was extensive.

There had been nods to the culture of those remembered there. The words chosen by CWGC’s first Literary Advisor, Rudyard Kipling, were carefully cast in bronze panels in English, Hindi, Urdu and Gurmukhi.

However, no names appeared on the war memorial when it was unveiled in 1926, only the names of their units or regiments.

The Commission had not been satisfied with the records of the missing provided by the army and colonial authorities and so no names were included. These were eventually obtained and included in the register.

As well as being a war memorial to the missing Port Tewfik stood as a memorial to the Indian Army which served in Egypt and Palestine during the War. Its two crouching tigers, embodying the Indian Army, stood guard over the entrance to the Suez Canal, the vital artery of Empire.

Imperial fortunes, however, would slowly wane. As Britain withdrew from lands it had once ruled, the commanding locations that had been chosen for memorials like this were suddenly harder to access.

A power mast was built next to the ruined Memorial, complicating any rebuild plans.

Following the memorial’s destruction in the 1960s, the Commission strove to restore it but by the 1970s, it became clear that a replacement memorial could not be built in the same location. On top of the area’s instability, a towering power mast had been hastily erected within metres of the ruins.

After long debate, it was decided to build a new memorial within the grounds of Heliopolis War Cemetery, in a Cairo suburb, 75 miles east. The Commission took the opportunity to redress the historical inequality and so physically included the names on the new memorial, so now all 3,727 men are commemorated there.

And now new tigers guard their memory. The symbolic spirit of the Indian Army was replicated in the new design with three bronze tigers placed at each of the war cemetery’s entrances.

The tigers, still crouching; the names, no longer hidden.

The symbol of the Indian Army, the original tigers were sculpted by Charles Jagger in 1925.

Constant repair and care

Ramleh WAR CEMETERY

Location: Ramleh, Israel Language: Hebrew Altitude: 66m Rainfall: 550mm

Temperature: 9°c - 35°c Biggest challenge: Weather and stone damage

You have to look closely to see where the scars have been repaired. Such is the care and skill used by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission’s (CWGC) teams in Israel, you’d often need to be told where the stonework has been altered.

On the Ramleh 1914-18 Memorial, at the heart of Ramleh War Cemetery, bullet marks from an incident last year by having been carefully restored and filled in. Most visitors would barely notice.

It’s not just the stonework that needs care and attention here. CWGC’s Israeli sites take a beating from the weather.

As with all over the world CWGC tries to use resources responsibly. Solar panels power the latest watering system as it ekes out every last drop to keep the grass as green as possible during the pounding heat of summer.

One by-product of the hot weather is the sweet, ripe fruit that adorns the date palms in our cemeteries here – enough to make any European gardener jealous.

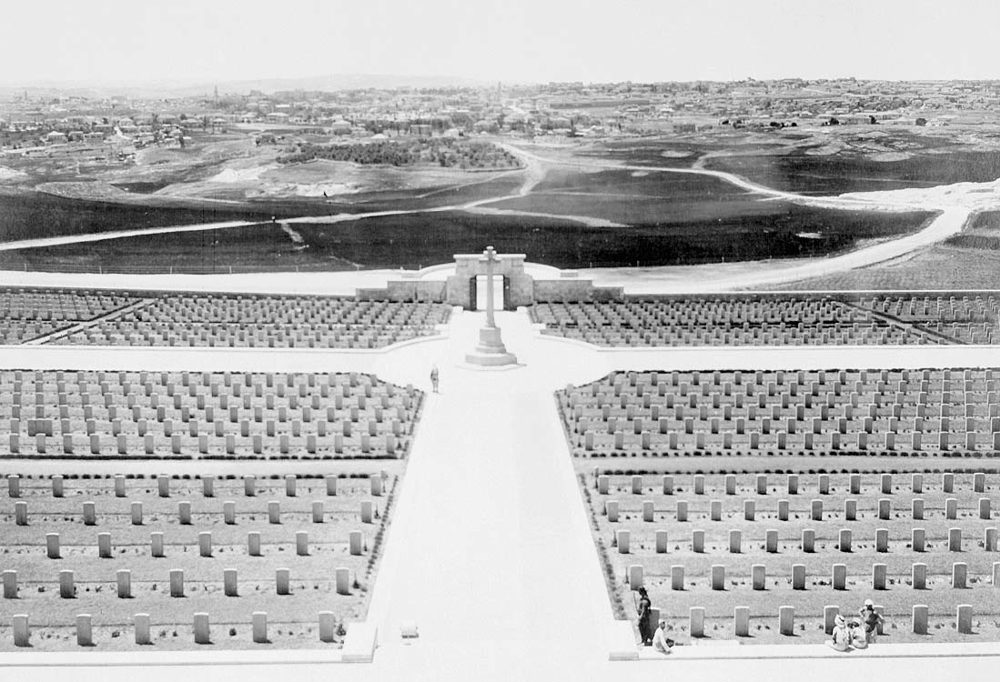

Jerusalem War Cemetery shortly after construction, seen here before the city expanded.

The main sites in Israel were first constructed after the First World War. Jerusalem War Cemetery stood high up on the hills on the outskirts of the city, crowned by the Jerusalem Memorial with its iconic mosaic interior – designed by Robert Anning Bell to honour more than 3,000 missing war dead.

The iconic mosaic interior in the Jerusalem Memorial's chapel.

Today, Jerusalem has grown up around the cemetery. Construction projects have temporarily impacted the main entrance. Overnight, drug users have taken to using the site, giving gardeners an extra clean-up duty in the mornings – all is cleared away quickly enough.

Those who work here are still hugely proud. Nader Habesh, a sculptor by trade, has worked as a mason for the Commission in Israel for more than a decade.

He said: “I feel so proud to work for the Commission. Through our work, we have been able to save many pieces of stonework in Israel and Gaza. It’s an honour to preserve these respectful reminders.” And if Nader’s done what he does best, you would barely know he’d done the work at all.

The Jerusalem Memorial.

gardens of the death railway

Thanbyuzayat WAR CEMETERY

Location: Thanbyuzayat, Myanmar Language: Burmese Altitude: 23m Rainfall: 2,378mm

Temperature: 19°c - 41°c Biggest challenge: Extreme weather

Pounding heat and flash floods – the weather in Myanmar poses the Commonwealth War Graves Commission its fair share of difficulties.

Our team here is responsible for maintaining nearly 12,000 graves, but the graves look a little different to those familiar with our work in Europe. Each one is marked by a bronze plaque set into the ground on a pedestal of stone.

In Myanmar bronze plaques take the place of Portland headstones to better withstand the climate.

These plaques weather better than Portland headstones in the intense heat and the rain of South East Asia.

In Yangon – known to the British during the Second World War as Rangoon – we face opposing problems from the weather.

Rangoon War Cemetery, in the busy city centre, gets regularly submerged by flash floods. Our gardeners have to sweep away debris on a daily basis in the rainy season.

The iconic Rangoon Memorial at the heart of Taukkyan War Cemetery.

Yet just one hour away on the outskirts, at Taukkyan War Cemetery, we face a constant battle against the parched ground in the brutally hot and dry weather.

Taukkyan is a vast cemetery with almost 6,500 graves. They are carefully laid out in rows around the distinctive shape of the Rangoon Memorial, which lists almost 27,000 missing war dead.

The war memorial is beginning to show signs of its age and we are preparing to restore it.

In its shadow, lies a more recent row of bronze plaques. They sit in a special plot, naming the 16 men aboard Dakota KN584.

The plane crashed in September 1945 killing all aboard. Only recently was it found they had been buried deep in the jungle, making recovery impractical. Instead, their relatives now have somewhere accessible to pay their respects with a row of special memorials in our war cemetery.

The last of our three sites in Myanmar is Thanbyuzayat. The cemetery sits a stone’s throw from the end of the infamous death railway.

A cross at the entrance to Thanbyuzayat, made from wooden sleepers on the death railway.

This cross-country route was built by forced labour, including prisoners of war, during the Second World War, in often gruelling conditions. It has been said that a man died for every sleeper laid across the 415-kilometre (258 mi) route of the railway. Many of those who died, lie at rest in CWGC’s care.

And as a reminder of what they went through, visitors to Thanbyuzayat will see a handmade wooden cross in the cemetery’s entrance, assembled out of those infamous railway sleepers by prisoners.

Our dedicated team in Myanmar.

The WAR graves hidden in a garden

Tbilisi British WAR CEMETERY

Location: Tbilisi, Georgia Language: Georgian Altitude: 479m Rainfall: 510mm

Temperature: -6°c - 32°c Biggest challenge: Cemetery lost in Cold War

The closest you can ever get to visiting Tbilisi British War Cemetery is by knocking, politely, on the door of a Georgian family home, and being guided through to their back garden.

The war cemetery itself no longer exists. All that remains is a marker in this garden, installed by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission in 2000, to record where it is believed the cemetery once stood.

The only indication of what lies in this garden is a small CWGC sign on this family's garage door.

Shortly after the First World War, this is where 31 men’s stories ended. They were far from home, here to occupy the country on behalf of the Allied Powers while the post-war map of the world was still being drafted.

The original grave markers have all been lost to time. Access to Georgia after 1919 was impossible for the Commission due to Communist rule.

While a small group of remaining British ex-pats helped tend to the war cemetery into the 1930s, the Second World War and then the Cold War made it too challenging to sustain.

By the time the Iron Curtain lifted, homes and gardens had been built over the site of the Tbilisi British Cemetery.

This marker was installed in 2000 by CWGC to show where the Tbilisi British Cemetery once was.

CWGC was stuck at arm’s length until well after the fall of the Iron Curtain. By the time we returned we were faced with the sprawling suburbs of Tbilisi, where there had once been an isolated cemetery.

In the interim, we had not forgotten those men and their names were engraved on the Haida Pasha Memorial in Istanbul.

Despite being 800 miles away from Tbilisi it was the nearest place where CWGC could guarantee long-term continued access. The shifting borders and political instability caused by the World Wars impacted our global task long after the conflicts ended.

While world events have left us with this odd legacy of making a pilgrimage to a family garden, it’s not just the Commission’s team who visits this home. Dignitaries and relatives return every Remembrance Sunday to pay their respects after knocking, politely of course, on this Georgian family’s garage door.

Gardening in the crosshairs

Wayne's Keep: Nicosia War Cemetery

Location: Nicosia, Cyprus Language: Greek, Turkish Altitude: 159m Rainfall: 324mm

Temperature: 9°c - 34°c Biggest challenge: Cemetery in buffer zone

Just getting to work is a real challenge for one of our Cyprus-based teams.

The war cemetery in question is less than an hour from our Mediterranean head office and sits just on the outskirts of the country’s capital.

The difficulty comes from the important invisible lines that surround Nicosia War Cemetery, or Wayne’s Keep as it’s often known.

Since the 1970s the disputed border between the southern and northern parts of the island has run right across the cemetery.

One side believes it sits in the buffer zone, and the other, that it sits firmly inside their territory.

A UN escort is needed for any CWGC staff or contractors to enter Wayne's Keep.

In places, the buffer zone is so untouched by human influence that species thought long extinct have been spotted.

Throughout half a century of land disputes, the Commission’s commitment has been difficult but not impossible to fulfil. Within this sliver of no man’s land, we are tasked with maintaining the graves of more than 200 Second World War dead and a series of memorials.

Next to them are close to 600 British military dead, servicemen stationed on the island after the War when it was still part of the British Empire or as part of the United Nations task force deployed to enforce the uneasy peace between north and south. CWGC continues to take responsibility for their graves on behalf of the MOD.

When access is restricted the horticulture on site begins to suffer.

To undertake even the most minor of work to the various sections of this cemetery, staff and contractors must gain special permission and be accompanied by a UN escort. Armed guards on the northern side are always present.

Surely there are few other gardeners in the world who mow the lawn under such watchful eyes.

As tensions rise and fall CWGC’s work continues to get caught in the mix. On more than one occasion people have been asked to leave the site by armed guards. For those living on the island, the presence of the border and the buffer zone is a part of daily life. We are in no position to challenge or question the wider situation.

Instead, we must continue to work peacefully with all involved to ensure those buried in the crosshairs of today’s dispute are not forgotten.

Borders full of colour are currently not possible to maintain due to limited access within the buffer zone.

BAck from destruction

Zehrensdorf Indian WAR CEMETERY

Location: Wünsdorf, Germany Language: German Altitude: 76m Rainfall: 591mm

Temperature: -8°c - 28°c Biggest challenge: Cemetery destroyed by tanks

Secluded in quiet woodland, next to an abandoned Soviet-era military base, 15 miles south of Berlin, lie the graves of 206 Indian servicemen of the First World War. Dotted between each headstone is a small burst of colour from the spread of flowers that are synonymous with our work.

Visitors would be forgiven for thinking Zehrensdorf Indian War Cemetery had always been this way.

But when the Iron Curtain lifted in the 1990s the Commission was faced with a disaster zone. A World War and a Cold War had destroyed the war cemetery. Not one headstone was left standing.

Almost nothing remained of the peaceful space that had been created to remember these men.

After the fall of the Berlin Wall, CWGC returned to Zehrensdorf to find it completely destroyed.

These Indian servicemen died while prisoners of war, captured by the Germans on the Western Front.

They were held at two camps at Zossen-Zehrensdorf which included large numbers of Allied PoWs of African and Asian descent. They were ‘show camps’ with better conditions than others and included the German Empire’s first mosque built especially for the Muslim prisoners. Many prisoners were then the focus of studies by curious anthropologists, keen to research the international mix of captives.

After the war, the Commission formalised the Indian cemetery at Zehrensdorf which formed part of a larger cemetery containing allied war dead of the First World War.

The original cemetery as it appeared before the Second World War.

Old visitor books from the cemetery in the 1930s show the local fascination with these men from far-off lands continued between the wars, though comments were increasingly accompanied by Nazi sentiments.

By the time the Second World War had drawn to a close, the Commission hoped it might be possible to return. But a new Cold War between East and West soon put an end to those hopes. We were only able to return long enough to find out that it was already damaged.

Held firmly behind the Iron Curtain staff were unable to gain proper access.

Despite damage from tanks using the ground for training, the headstone beams and graves below were undisturbed.

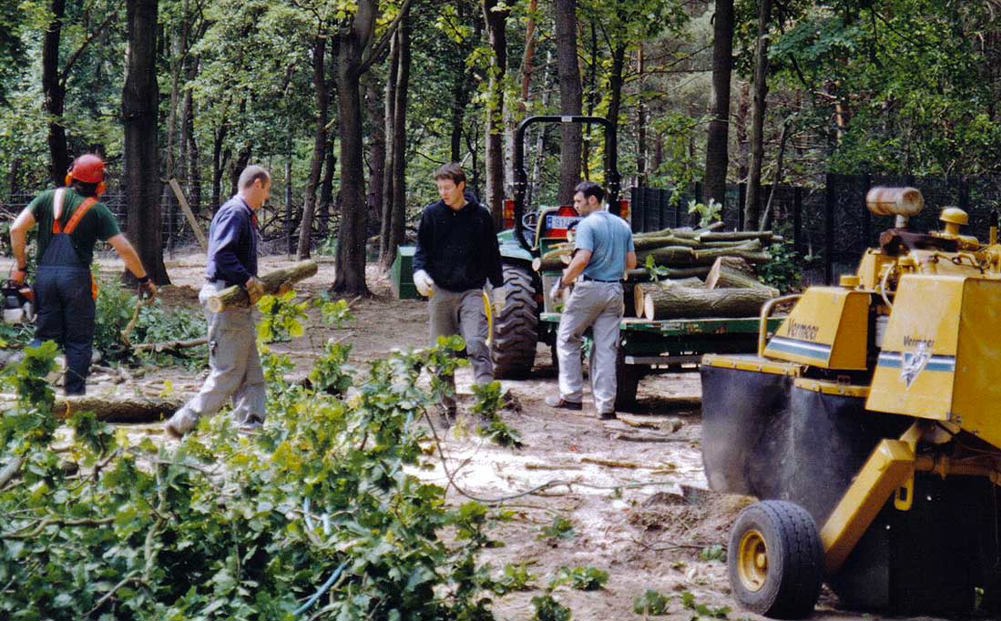

When they eventually returned after the Fall of the Berlin Wall they found the site had been all but wiped off the face of the Earth. But, underneath the overgrowth and debris, in spite of tanks using the area for training exercises, the beams that once held headstones were somehow intact.

Before repairs at Zehrensdorf could begin, unexploded ordnance had to be safely removed and the area cleared.

Brand new white Portland headstones replaced those that had been destroyed.

One by one, once the area had been cleared of explosives, we were able to assure ourselves that no human remains had been affected. Each grave could still be marked in its original position. New headstones were produced, and great efforts were taken to ensure everything was replaced exactly.

The old damaged Stone of Remembrance was donated to a nearby museum.

The final piece in the restoration was installing a brand new seven-tonne Stone of Remembrance.

The final, heavy, piece of the puzzle was installing a brand new Stone of Remembrance – all seven tonnes of Portland stone. The only evidence that remains of the damage is the original Stone of Remembrance, preserved at a nearby museum.

Zehrensdorf Indian Cemetery, post reconstruction, once again filled with colour.