What will I see at a CWGC Cemetery?

With WAR cemeteries all over the world, many will look exceptionally different, but there are many aspects that are recognisable wherever you go.

Are there different kinds of cemeteries?

CWGC war cemeteries look different depending on when and where they were formed. Here are some of the most common examples:

Battlefield cemeteries

These are cemeteries that were created during the war, with graves dug by soldiers for their fallen comrades. As a result, these are often quite small sites, that would’ve been created very quickly.

Although small, these cemeteries can also contain mass graves, where a number of men were buried together in a trench or shell hole. The proximity of these sites to the fighting meant that they could be later damaged or destroyed and carefully marked graves might then be lost. This leads to battlefield sites often containing a large number of soldiers ‘known unto God’.

Medical cemeteries

These cemeteries were also created during the war for casualties that died as a result of injuries or illness. They are much more carefully laid out than battlefield cemeteries to make the most of the space available.

The burials at these cemeteries were often made in date order, which means that the successive units taking part in a battle can be traced in order of participation through the row and plots within the cemeteries as the war dead were buried each day. These cemeteries were often further from the front lines, so tend to be intact with identifiable graves.

Civilian/churchyard cemeteries

These sites have burials made during the war in existing civilian burial grounds. In the early years of the war, or when military units first arrived in a new area, the existing civilian cemeteries were often used for the burial of military dead. These graves are often scattered amongst the civilian burials, in small plots, or along the cemetery boundary. In France and Belgian, municipal village or town cemeteries are usually called ‘Communal’. In the UK, the majority of our war graves are in local churchyards or cemeteries, scattered amongst the civilian graves.

Extension cemeteries

After a period of prolonged military presence, existing civilian cemeteries and churchyards would often run out of space for further burials. At this point, a new cemetery would be begun. Sometimes this meant creating a new cemetery alongside the civilian site, and these are known as ‘extension’ cemeteries. These sites tend to share characteristics with medical sites, e.g. ordered to take advantage of available space but without any overarching design.

Concentration cemeteries

These cemeteries were created after the war. After the Armistice, the former WW1 battlefields were cleared of the debris of battle. Thousands of small cemeteries and isolated battlefield burials littered the landscape and the decision was taken to concentrate all the isolated graves and many of the smaller cemeteries into existing sites or to create new cemeteries where the graves could be better tended.

What are some of the common features of a CWGC cemetery?

While CWGC headstones are instantly recognisable, some of the other aspects of our cemeteries are equally iconic. Below are some of the features you might see on trips to our sites.

Cross of Sacrifice

Designed by Sir Reginald Blomfield, the stone cross with a downward sword reflects the faith of the majority of those commemorated in the cemetery.

Initially known simply as the ‘Great Cross’, it later became known as the Cross of Sacrifice. The cross is usually found in sites with over 40 commemorations and it varies in size depending on the size of the cemetery. We use four different sizes, which range in height from 4.4 metres to just over 9 metres, depending on the size of the cemetery in which it is placed.

The base is octagonal and allowed further flexibility in the design meaning that the whole structure was capable of being incorporated into walls or allowing for seating features at its base.

Stone of remembrance

Also known as the ‘War Stone’ or ‘Great Stone’, this feature is usually only found in larger cemeteries. Designed by Sir Edwin Lutyens, it is carved out of a single piece of stone and is inscribed with words chosen by Rudyard Kipling: ‘Their Name Liveth for Evermore’.

Each stone is the same size regardless of the size of the cemetery it is placed in. To the naked eye, they seem like straight-edge pieces of stone, but the top of the stone is not flat, it's slightly curved. This is an architectural technique called Entasis. If you continue the curve of the stone it would form a sphere with a radius of nine hundred feet. This technique helps to give the stone a feeling of solidity and gravitas.

Designed to mimic an altar, the stone evokes a religious sentiment to appeal to multiple faiths and symbolises the sacrifice made during both world wars.

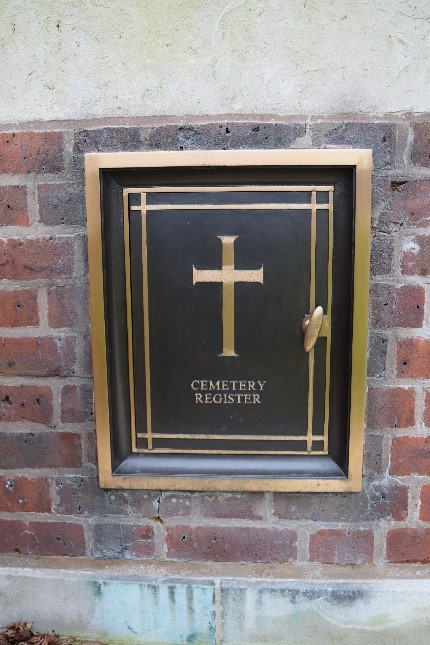

Cemetery Register Box

These can usually be found built into the walls of the cemetery or shelter buildings. Inside is a register listing the known details of those buried or commemorated at the site, along with a plan which maps the burial plots, rows and graves.

There will usually be a visitors’ book included, where messages and comments can be recorded.

Gift of land tablet

In many of the Commission’s sites, there will be a tablet with words similar to this, written in English and the local language:

“The Land on which this cemetery stands is the free gift of the Belgian people for the perpetual resting place of those of the Allied armies who fell in the war of 1914-1918 and are honoured here.”