21 January 2022

The importance of war memorials

Tributes to the fallen, war memorials are found all across the world and mark many different conflicts, including the two world wars at the start of the last century. Laura Reynolds, CWGC’s Works Project Manager, explores the importance of war memorials, their construction and how they’re being maintained today for future generations.

What is a war memorial?

War memorials are erected to commemorate those who died in a war, to record a victory or particular battle. The sheer variety of war memorials types found across the world is testament to their importance in reflecting the feelings of the different communities and organisations that had them erected. They come in many forms including whole buildings or building components (such as a commemorative window), monuments, sculptures, gardens and designed landscapes, shrines of remembrance and even digitally - such as the CWGC digitised rolls of honour.

How many war memorials are there?

The Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC) cares for over 200 war memorials located across the globe, created to commemorate 763,425 casualties of the Commonwealth forces who died during the world wars. Across the world, there are countless war memorials built by local communities, from small village memorials to large national memorials.

What is the purpose of memorials and monuments?

Memorials dedicated to the war dead provide a place of remembrance for those who lost loved ones and have no grave to visit, and act as a point of engagement for the wider population with the events that shaped so much of our lives today.

The importance of memorials and monuments

Whether it’s the Brookwood Memorial in the United Kingdom or the Rangoon Memorial in Myanmar, CWGC’s memorial’s all around the world play an important role in commemorating the war dead and offer a place of reflection.

Memorials provide a way to remember those in military service who lost their lives during World War One and World War Two, and have no known grave or can’t be commemorated where they’re buried.

Services & pilgrimages

In the 7th annual report of the commission, Major-General Fabian Ware describes how the war dead “deserved perpetuity in Sepulchre... [that this was] previously reserved for the former ‘great of the earth’, most commonly by burial in some historical or sacred monument such as Westminster Abbey or other cathedrals, [and that] since the war dead could not be brought in their hundreds of thousands beneath the sacred shelter of existing monuments, structures at least as lasting must be erected in distant lands”.

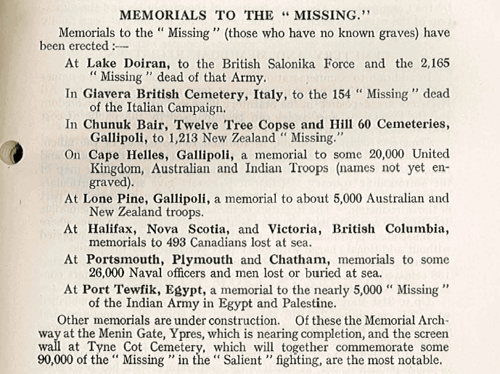

Many of these structures were ‘memorials to the missing’ and the annual report goes on to list progress on those constructed around that time (in 1927):

- Doiran Memorial

- Giavera Memorial

- Chunuk Bair (New Zealand) Memorial

- Twelve Tree Copse (New Zealand) Memorial

- Hill 60 (New Zealand) Memorial

- Helles Memorial

- Lone Pine Memorial

- Halifax Memorial & Victoria Memorial

- Portsmouth Naval Memorial

- Plymouth Naval Memorial

- Chatham Naval Memorial

- Port Tewfik Memorial

Extract from 7th annual report, CWGC.

“Each dominion took a different approach to memorials: New Zealand opted for several small memorials spread geographically according to where their troops had fought, while Canada chose one enormous structure – the Vimy Memorial – to commemorate all its missing soldiers in France”.

These memorials, as a place of commemoration for those without a known grave, were sometimes the last remaining tangible connection relatives had with their loved one on Earth. They have attracted huge numbers of pilgrims both then and now; as a form of closure for those left behind, or a more collective sense of mourning of everything lost through the war.

An aerial film clip shows the mass of pilgrims who attended the opening of the Vimy memorial in France, during the King’s visit.

Why are war memorials important to us?

The importance of war memorials is arguably timeless, with pilgrims still visiting today for various reasons and sometimes travelling considerable distances. At Le Touret memorial in France, a man and his wife, having travelled on motorcycle all the way from Scotland, to play the bagpipes belonging to his Great Uncle who was commemorated on the memorial, created their own moving, and personal tribute in this way.

In some cases, the connection to the deceased may be more distant, but can even assist a person’s sense of belonging by clarifying genealogical links for those without or not close to family. The war dead archival and research resources that CWGC provides assist many in this way.

Why are memorials important to society?

CWGC memorials across the world also provide a vital focal point for regular services held by various groups. For example, in 2018, the Royal British Legion recreated the Great Pilgrimage of 1928, with standards from each branch paraded through the Menin Gate in front of thousands of veterans, friends, and family, just as they were in 1928.

How were war memorials designed and built?

Some elements of a CWGC memorial cemetery were consistent, i.e. the cross of sacrifice and stone of remembrance were replicated to a consistent design by commission Architects. However, individual war memorials allowed a greater sense of freedom for the designer and this is reflected in their variety across the commonwealth.

As with most structures, practical requirements heavily influenced the design of war memorials. The challenge with large memorials was to provide space to record the names of thousands of casualties. This required a large surface area, and at Thiepval, Sir Edwin Lutyens designed an ingenious system of arches that would provide multiple internal elevations to accommodate some 72,000 names.

One of the founding principles of the CWGC (then IWGC) was equality in commemoration, regardless of religion, rank or social standing and this is again often reflected in the design of war memorials, such as at Rangoon memorial in Myanmar (seen below). H J Brown selected a circular centrepiece to allow inscriptions to be made in English, Urdu, Hindu, Gurmukhi and Burmese in positions of equal importance.

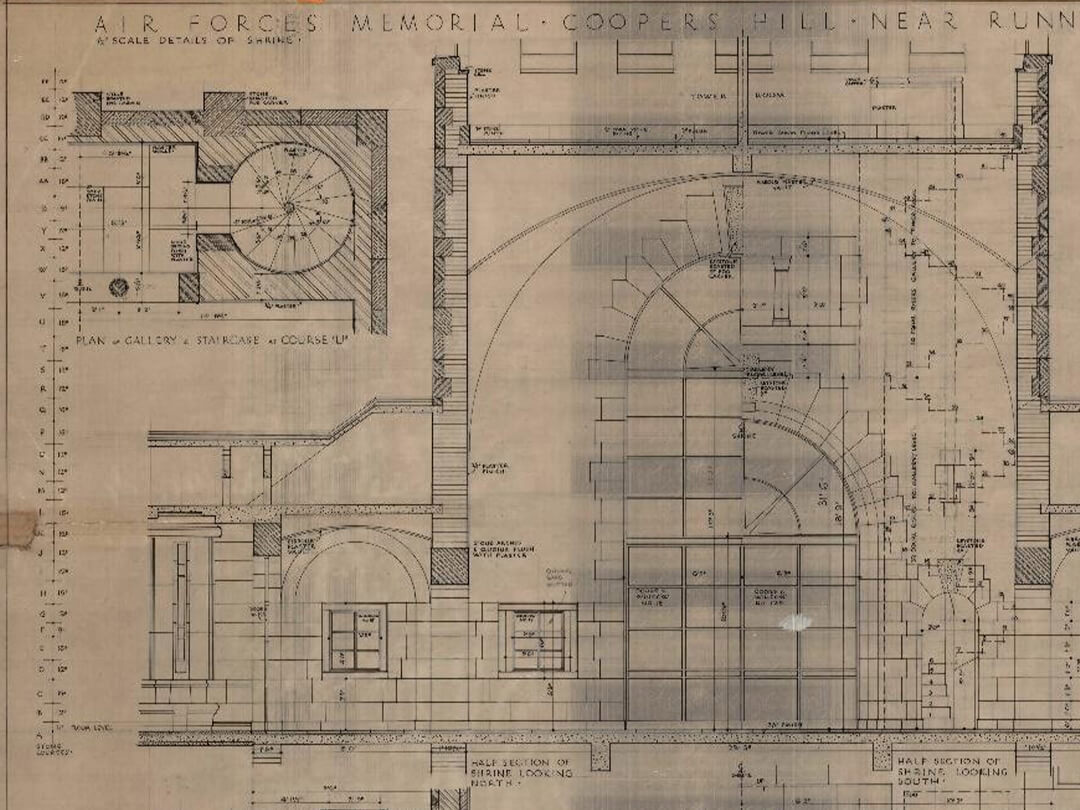

Portland stone is a commonly used material in CWGC war memorials, due to its compressive strength, longevity and aesthetic qualities. The image below shows construction of the tower at Runnymede memorial which was designed by Sir Edward Maufe. You can see that stone was stored on site and then craned into place over timber centring (temporary shoring) to form the principal arch.

War memorial conservation and listed war memorials

Many of the war memorials CWGC cares for were designed by world renowned Architects, sculptors and artists and have their heritage values recognised either under Listing or even as designated World Heritage Sites. However, a lot are now almost 100 years old and sometimes as the result of original construction defects, normal weathering and erosion (or often both) they are subject to physical deterioration.

Recognising that complete preservation is unrealistic, and in an attempt to balance this situation, in 2020 CWGC launched a series of Conservation policies. These aim to manage change sustainably whilst preserving the significance and heritage values of the CWGC historic estate.

How does CWGC maintain its war memorials?

Although conservation is approached in a pragmatic way according to these policies, CWGC war memorials still require essential maintenance and sometimes far more extensive repair projects.

Each memorial has unique challenges. All of our changes try to stay as close to the original design as possible, including using original materials. Some of our latest projects are:

- Minor repairs and maintenance, such as repointing shown here to Brookwood memorial.

- Thiepval memorial, France is currently in phase two of a major memorial restoration project, which saw completion of works to roofs, rainwater goods and the main brick arch in 2016, and is currently restoring internal drainage, brick facades and paving, and commemorative name panels.

- Le Ferte-Sous-Jouarre memorial to the missing is undergoing a 9 month programme of repairs to secure the foundations, carry out masonry repairs and improve drainage.

- The roof and decorative ceiling paintings have undergone conservative repair at Runnymede Air forces memorial in Surrey, UK.

What is the purpose of a memorial in the 21st century?

For those who erected CWGC’s memorials after the two world wars, the purpose of these monuments was clear; to remember the fallen and pay respect to their sacrifice. But today, almost a hundred years on do these memorials still serve the same purpose?

Today memorials have become a place to perform acts of remembrance, whether that’s a huge military service or a single person visiting the name of their great grand grandfather.

CWGC’s memorials are also somewhere where names are listed for all to see: names of merchant seaman who have no known grave but the sea, air force personnel lost whilst flying sorties over enemy territory or men lost during battle who cannot be identified.

Most importantly, these war memorials act as a physical reminder of the cost of war. There is nothing quite like standing in front of an immense memorial like the Vimy Memorial or the Singapore Memorial, seeing all the names reaching up into the air and realising the shear loss of life caused by the two world wars.

How to find a war memorial

From UK war memorials to commemorative sites around the world, you might now feel inspired to visit one of these locations yourself.

CWGC has built war memorials across the globe, commemorating the missing of the two world wars. Find information about our war memorials online and make your own pilgrimage by visiting a local war memorial near you.