03 October 2022

The True Story of the Bridge over the River Kwai

One of the most iconic war films of its time, The Bridge on the River Kwai has shone a spotlight on POWs' suffering. But what’s the real story? Let’s find out.

Image: Bridge 277 aka the real Bridge over the River Kwai

Is the bridge over River Kwai real?

Image: The iconic poster of the 1957 classic

Image: The iconic poster of the 1957 classic

David Lean’s 1957 epic The Bridge on the River Kwai is regarded as one of the all-time great war films.

Starring Alec Guinness, it depicts the struggles and defiance of Japanese prisoners of war building the fictional Burma railway between 1943-44.

The film was based on the 1952 novel Bridge over the River Kwai by Pierre Boulle. Boulle drew on the experiences of Far East POWs building the now infamous Burma-Siam Railway, linking modern-day Myanmar and Thailand to create his work.

The Bridge on the River Kwai was a smash hit on release. It was the highest-grossing film of 1957 and scooped up seven Academy Awards, including Best Film, Best Director, and Best Actor.

When it first graced the silver screen, the film won the admiration of audiences everywhere and continues to do so. For many, it’s their first exposure to the horrors prisoners of war suffered in the Far East.

The bridge depicted in the film is most definitely real. In fact, there were two: one a wooden railway bridge and the other a ferroconcrete structure built using imported bridge sections from Japanese-controlled Java.

It’s this structure, Bridge 277, that still stands and is a famous local tourist attraction.

But, what about the real men behind the real story of the construction of the Burma-Siam Railway? Let’s examine the history behind the film and the men who made it.

What was the Burma-Siam Railway?

The Burma-Siam Railway was 250 miles of railway constructed by Allied prisoners of war alongside forced Asian labourers.

Image: British troops surrender at Singapore

Image: British troops surrender at Singapore

Its construction came about because Japan needed another supply route to link Singapore and Malaysia to its possessions in Burma following Singapore’s fall in February 1942.

By this time, the United States and its naval and industrial might had entered the war. Victory over the Japanese navy at Midway in June 1942 was the turning point in the Far East and Pacific. The US was beginning to control the sea lanes, making it increasingly difficult for Japanese shipborne cargo to reach the army dotted across the Pacific.

Before the US began rolling up Japanese possessions throughout the Pacific, and the British gained significant momentum in Burma, Japan had already carved out a substantial empire. It stretched from Japan, Korea, and China in the north all the way down to Indonesia. Supplying it by ship was the only practical solution.

To counter the Allies’ tightening grip on supply lines, the Japanese army resurrected an old idea first mooted by regional powers in the late 19th century: construction of a railway between Myanmar and Siam.

It would be a massive undertaking. Initial estimates from Japanese engineers suggested it would take five years.

Imperial Japanese Army Command deemed this unacceptable. Rather than draw on its own corps of manpower, which was busy fighting an eventual losing battle against encroaching Allied forces, it would put its legions of POWs and local forced labourers to work.

Construction of the Burma-Siam railway began in October 1942 and would end in October 1943.

By the end, prisoners working on the rail route weren’t calling it the Burma-Siam Railway. They were calling it the Death Railway. Workers died at a rate of 20 men per day.

Rather than starting at two ends and meeting in the middle, as is normal in railway construction, the Japanese created hundreds of camps along its length.

All but a small section of the route was built in dense, malarial jungles, in sweltering heat and monsoon rains. Some sections, such as the infamous Hellfire Pass, required carving through tough, sheer rock.

POWs and indentured labourers were worked harshly while constructing the railway. Although work camps were set up at 100-metre intervals, Burma-Siam Railway labourers and prisoners of war slept in rudimentary bamboo huts on filthy floors in appalling conditions. Food and medical supplies were either nonexistent or rationed pitifully.

Image: Brigadier Arthur Varley

Image: Brigadier Arthur Varley

Their taskmasters were relentless. As Australian Brigadier Arthur Varley put it:

“The Japanese will carry out their schedule and do not mind if the line is dotted with crosses.”

Brigadier Varley would survive the hellish building work along the Burma-Siam Railway but not the war. Along with 1,250 other POWs, he died while in transit from Singapore to Japan aboard the Rakuyo Maro transport ship after it was torpedoed by a US submarine.

He is commemorated on the Labuan Memorial, Malaysia.

Despite the nightmarish conditions and equipped only with the most basic of tools, the POWs pulled off an amazing feat of engineering. The Burma-Siam Railway’s construction necessitated the construction of over 670 bridges and numerous cuttings, all carved out by hand by a battered, starving, brutalised workforce.

For all the death and misery caused by its building, the Burma-Siam Railway only ever carried two Japanese divisions and 500,000 tons of supplies before VJ Day brought the war in Asia to a close.

Death Railway was bombed heavily by the Allies from 1943 onwards. By 1944, its operational capacity was being massively hampered by the damage caused by air raids.

The Bridge over the River Kwai met its fate in 1945.

The events depicted in the film, of a chaotic Commando raid and Lt. Col Nicholson’s wounded body falling dramatically on the detonator and blowing the bridge up, are completely false.

Allied bombers struck the wooden bridge and its concrete counterpart in February 1945 with one of the earliest uses of guided bombs in history.

Parts of the Burma-Siam railway still stand. Other parts have been placed in various local war museums. The surviving sections stand as monuments to the men who suffered so much to build them.

Where was the bridge over the River Kwai?

The real Bridge over the River Kwai is bridge 277 of the Burma-Siam Railway.

It spans the lazily winding Khwae Noi at Kanchanaburi, Thailand.

A small tourist train offers rides across the bridge’s span, while pedestrians can also travel over it on foot.

Cafes and tourist spots dot the banks of the Khwae Noi. It’s a charming, idyllic spot, belying the intense horror and suffering the men who built it went through.

Who were the men who built the Burma-Siam Railway?

60,000 or so Allied prisoners of war, including British, Australian, Dutch and some US troops, alongside more than 200,000 civilian labourers, were pressed into service.

Forced labourers were labourers taken from the populations of Japan-conquered territories. They included Chinese, Malayan, Burmese, Thai, Indonesian and Singaporean people.

They would work in appalling conditions, given minuscule amounts of food, snatches of sleep, and little to no medical treatment.

Image: Lieutenant George Hamilton Lamb

Image: Lieutenant George Hamilton Lamb

The trials of Australian Army Lieutenant George Hamilton Lamb reflected the men’s awful experience building the Burma-Siam Death Railway.

Lamb, as he was known, had been a politician before calling up, serving the state legislature in Victoria, Australia. He joined up in 1940 and served in the Middle East with the 2/2nd Pioneer Battalion before transferring back to the Dutch East Indies in early 1942.

It was not long before the Japanese army, which had overrun Java, captured Lieutenant Lamb and his men. They were soon sent to Thailand to begin labouring on the Death Railway.

Like thousands of other POWs, Lamb was kept in degrading conditions, refused medical treatment and barely fed. He was listed as missing in action in June 1943. Lamb’s sister received a letter from him in September 1943, saying he was in “excellent health” and being treated well by his captors.

Just two months later, Lieutenant Lamb was dead. He succumbed to malaria, dysentery, and malnutrition at Camp Kilo 101 in Thailand. Today, he rests alongside his fellow POWs in Thanbyuzayat War Cemetery in Burma (Myanmar).

Disease was a huge killer among railway workers, but so was brutality.

Japanese guards were known for their cruelty and would frequently torture and assault their prisoners. During the cutting of Hellfire Pass, for example, 69 men were beaten to death over twelve weeks.

The building of Bridge 277, the eponymous bridge that gave Lean’s film its name, was overseen by 2,000 British and Dutch prisoners of war. They were supported by an unknown number of Malaysian labourers.

Image: Lieutenant-Colonel Phillip Toosey

Image: Lieutenant-Colonel Phillip Toosey

At their head was Lieutenant-Colonel Phillip Toosey. Toosey would inspire the character of Lt. Col Nicholson, portrayed by Alec Guinness in the 1957 film.

Surviving veterans consider Toosey one of the finest officers they ever served under. His compassion and insistence on equality amongst the ranks ensured he protected his men as best he could. Of course, he could not save many of his men from expiring, but he did his best to make conditions more comfortable.

Those who were there did not think much of the novel or film of The Bridge on the River Kwai. Servicemen who survived the death marches, appalling working conditions, and savage treatment by their guards thought the film nor book reflected the realities of their experience.

They felt none of The Bridge on the River Kwai cast could fully understand or represent what it was like to be there.

John Coast, a young British officer who went on to become a successful filmmaker who spent three and half years as a Japanese POW, said: “As nobody should ever have need telling, the picture is a load of high-toned codswallop.”

One of the biggest causes of ire was the treatment ofa Toosey. In the film, Lt. Col Nicholson is seen collaborating with his captors, even under duress. Toosey’s men stated this never happened. Instead, the Lt. Col would stand up for his men when necessary to try to alleviate some of their hardships.

Want more stories like this delivered directly to your inbox? Sign up for our newsletter for regular updates on the work of Commonwealth War Graves, blogs, event news, and more.

Sign UpHow many Commonwealth troops died building the Burma-Siam railway?

As one British POW wrote:

“Everywhere in the jungle, the graveyards made their appearance; starting in a small way they gradually grew bigger, until when the railway was completed at the end of the year, thousands of bodies lay in the jungle from one end to the other.”

It’s estimated around 16,000 Allied prisoners of war were killed during construction of the Burma-Siam Railway.

Civilian workmen suffered terribly too, with their casualties far outstripping the military personnel. Around 90,000 forced labourers are thought to have died building Death Railway.

Where are they commemorated?

The casualties of the Burma-Siam railway were often buried in camp burial grounds located close to where they originally fell.

After the war, their remains were moved from these makeshift war cemeteries and graveyards to purpose-built Commission sites. American casualties were repatriated back to the United States.

The key sites containing Thailand and Burma war graves related to Death Railway and the Bridge on the River Kwai are:

Kanchanaburi War Cemetery

Kanchanaburi War Cemetery is located a short distance from the former Kanburi POW camp. Kanburi wasn’t a work camp as such. It was more of a transit hub where prisoners were moved to other work areas along the railway route.

The cemetery was established by the Army Graves Service to hold casualties made along the railway’s southern Bangkok to Nieke section.

Some 5,000 Commonwealth World War Two casualties are buried or commemorated in Kanchanaburi. They are joined by approximately 1,850 Dutch casualties and one non-war grave.

Showing the impact of disease on the workforce, Kanchanaburi contains two graves holding the ashes of 300 Cholera victims. A Cholera epidemic swept through Nieke Camp between May-June 1943. Victims were cremated and their remains are buried in the aforementioned graves.

The Kanchanaburi Memorial sits with the cemetery grounds. This records the names of 11 Indian army men buried in Muslim cemeteries throughout Thailand whose graves could not be maintained.

Kanchanaburi town is located around 130 kilometres northwest of Bangkok.

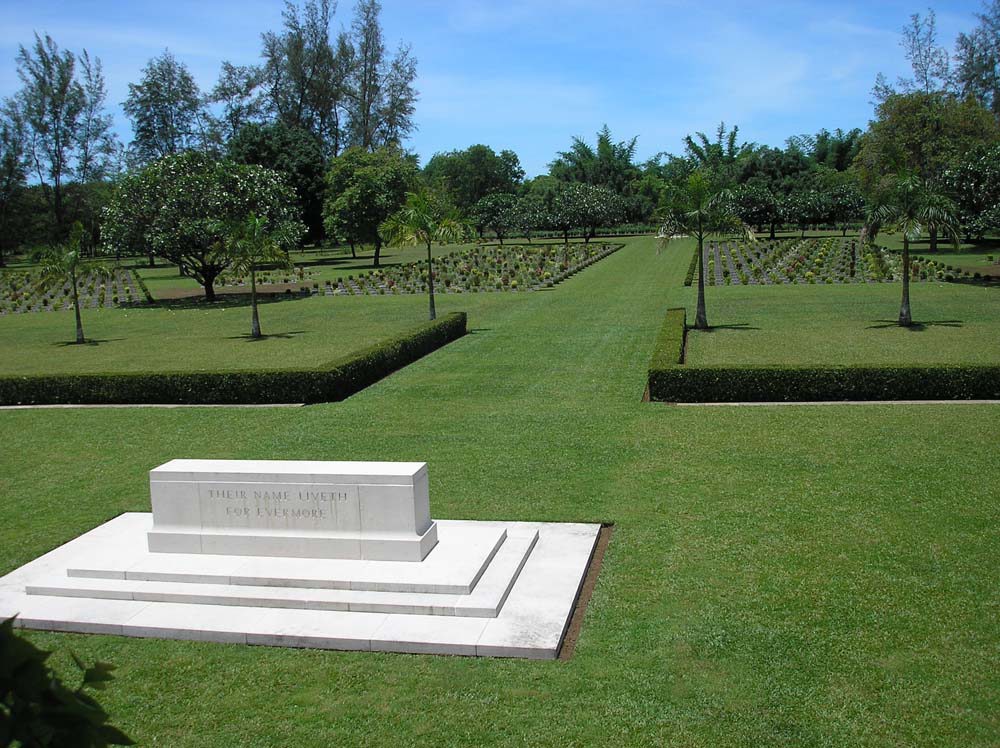

Chungkai War Cemetery

Chungkai War Cemetery is something of a sister site to Kanchanaburi. The cemetery itself is located just outside the town of Kanchanaburi at the point where the Kwai splits into the Mae Khlong and Kwai Noi rivers.

Chungkai was also a POW worker base camp. Allied soldiers had built a church and a hospital on the site where the cemetery now sits. In fact, the cemetery is the original burial ground started by the prisoners themselves.

Casualties commemorated at Chungkai are mostly men who died in the field hospital set up by prisoners. It’s telling that the railway workers had to see to their own medical care.

Thanbyuzayat War Cemetery

Like Chungkai and Kanchanaburi, Thanbyuzayat War Cemetery was originally part of the camp set up serving the Burma-Siam’s construction. Unlike the other two, it is not located in Thailand. Thanbyuzayat is in Myanmar.

Around 3,100 Commonwealth Burma war graves can be found at Thanbyuzayat, alongside roughly 620 Dutch burials.

Thanbyuzayat was originally a POW administration headquarters and base camp. It was set up at the beginning of the Burma-Siam’s construction. In January 1943, a base hospital was organised to care for sick and injured prisoners and labourers.

Ironically, Allied bombing raids of the region between March and June 1943 contributed to casualties sustained around Thanbyuzayat.

Following the raids, Thanbyuzayat was evacuated. Prisoners, including the sick, were marched to camps further along Death Railway. Thanbyuzayat continued to be used as a POW reception centre to reinforce work parties along the Burma-Siam Railway.

Support our work to keep their memories alive

As the Second World War fades from living memory, it's never been more important to keep the legacies of those who gave their lives in this world-changing conflict alive. You can help us do that by supporting the Commonwealth War Graves Foundation.

Support our work and help honour the 1.7 million who never returned home

The world wars have been providing the background for cinema for decades. Operation Mincemeat, starring Colin Firth, is the latest war time epic, with a surprising link to the CWGC.

Discover the true story of Operation Mincemeat

Author acknowledgements

Alec Malloy is a CWGC Digital Content Executive. He has worked at the Commonwealth War Graves Commission since February 2022. During that time, he has written extensively about the World Wars, including major battles, casualty stories, and the Commission's work commemorating 1.7 million war dead worldwide.