Equality in commemoration

“a nucleus of permanent co-operation founded on a community of sacrifice”

Fabian Ware, IWGC 10th Annual Report, 1928-29

From the outset, the Commission had to delicately negotiate relationships with the bereaved from across the UK and the world. We needed to arrange the practicalities of commemorating so many people, whilst ensuring that voices from different nations and communities were heard.

THE Families make their mark

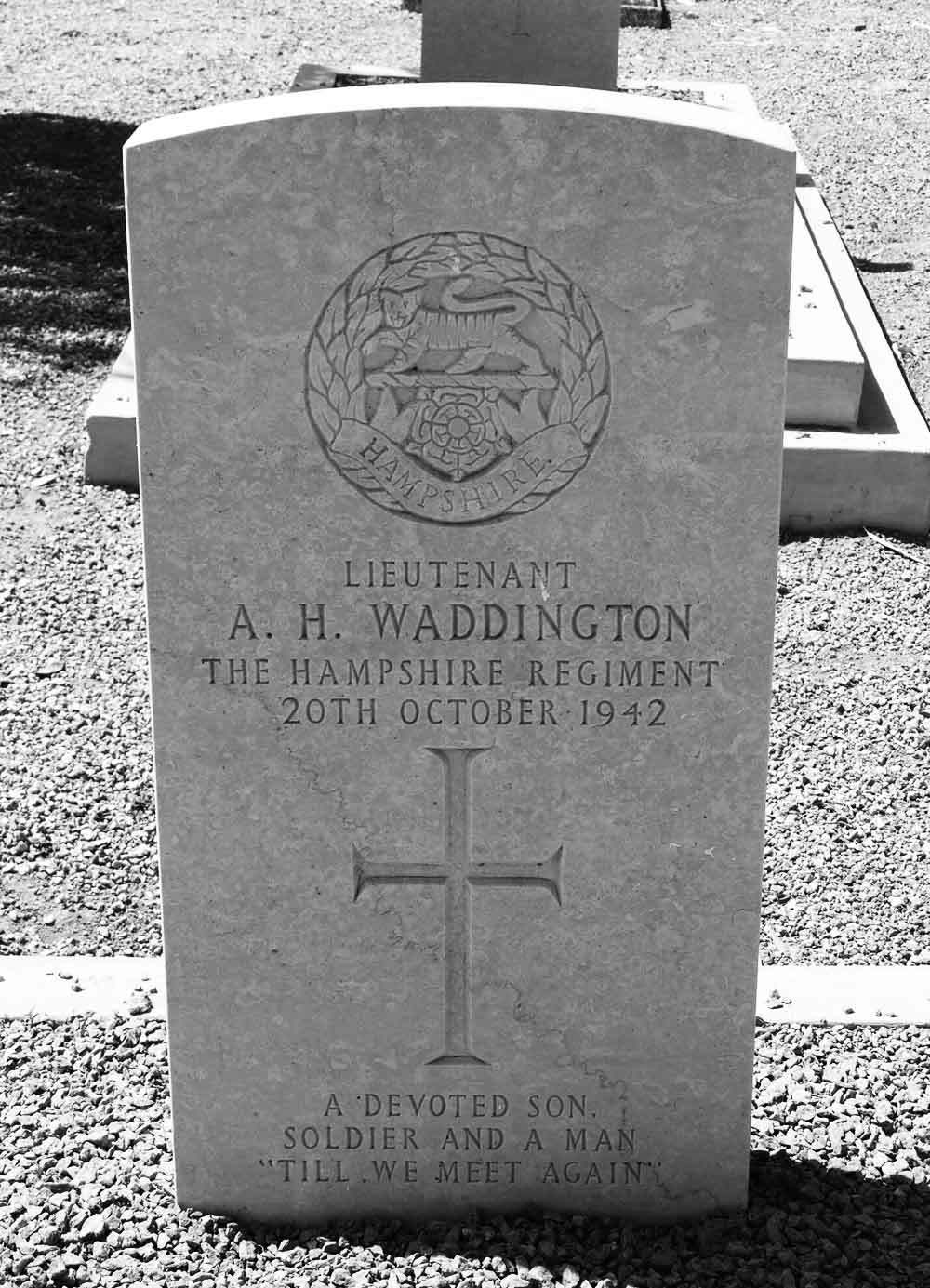

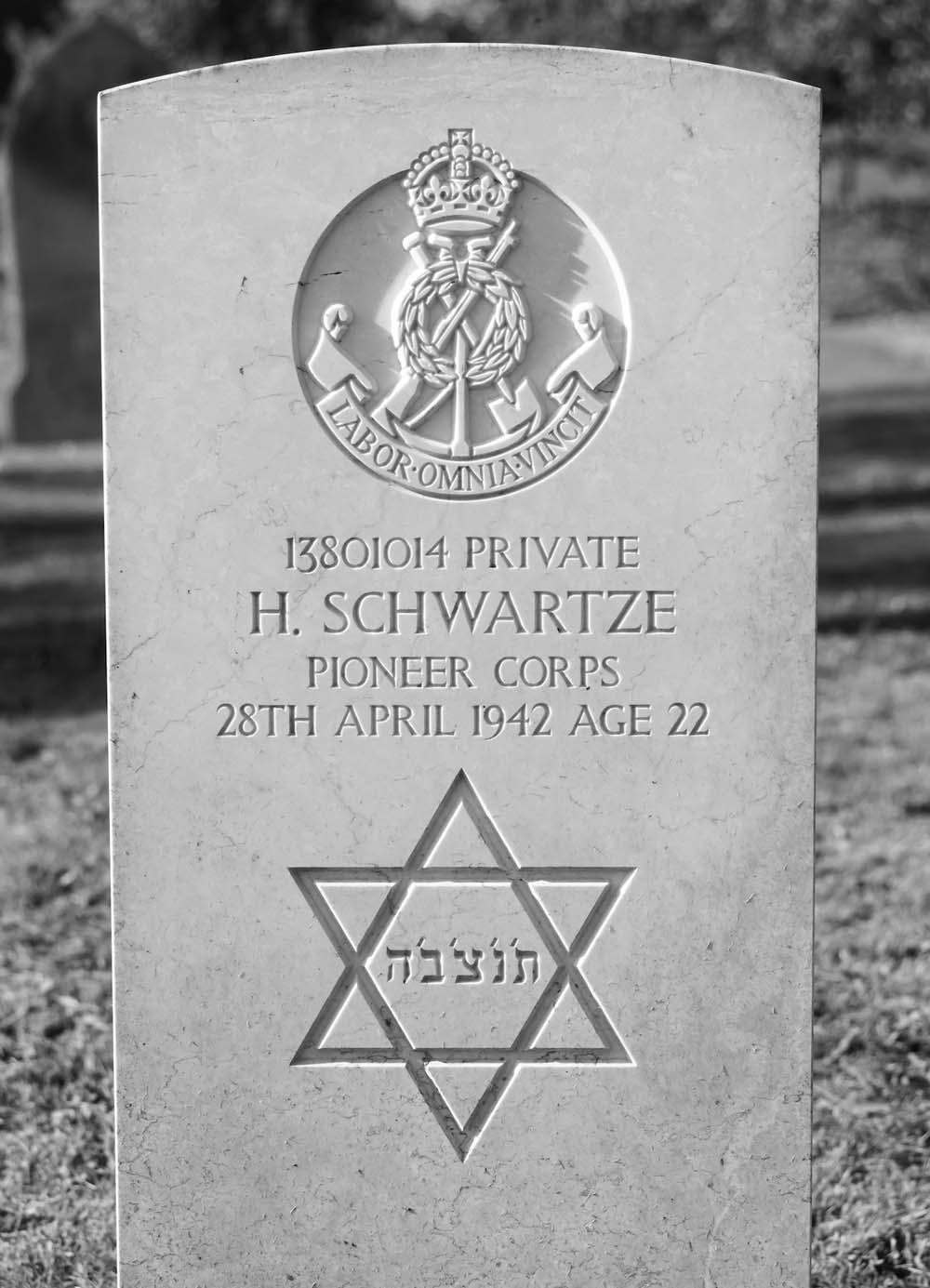

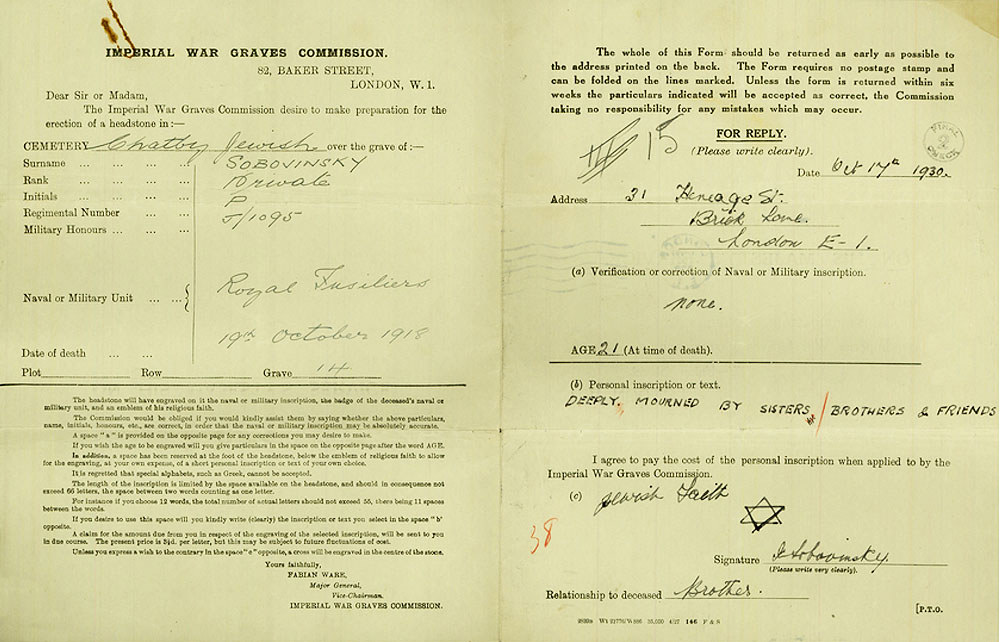

There were two contributions that loved ones could make to the headstone of identified casualties: specifying a religion and writing a personal inscription. Both were problematic.

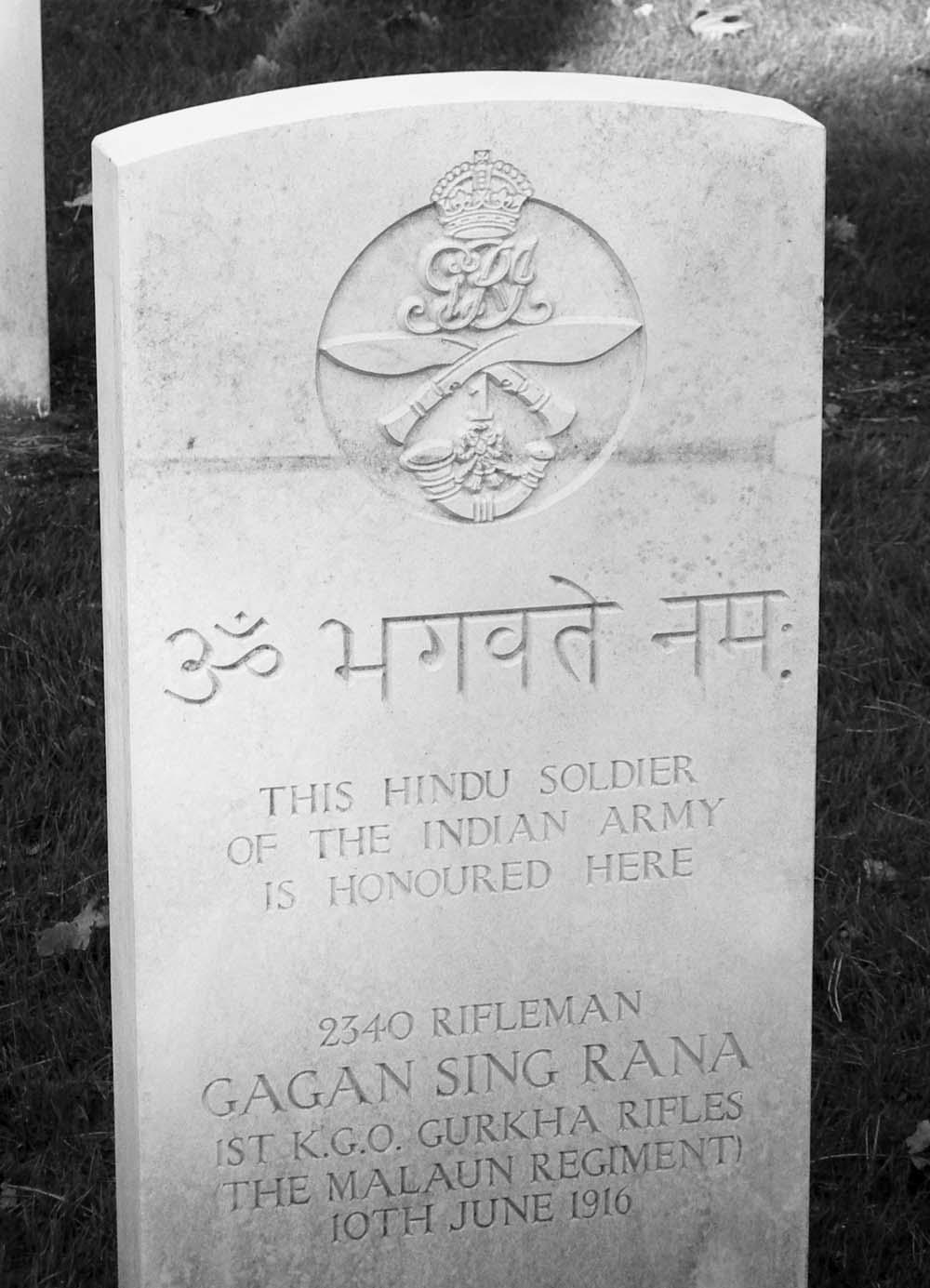

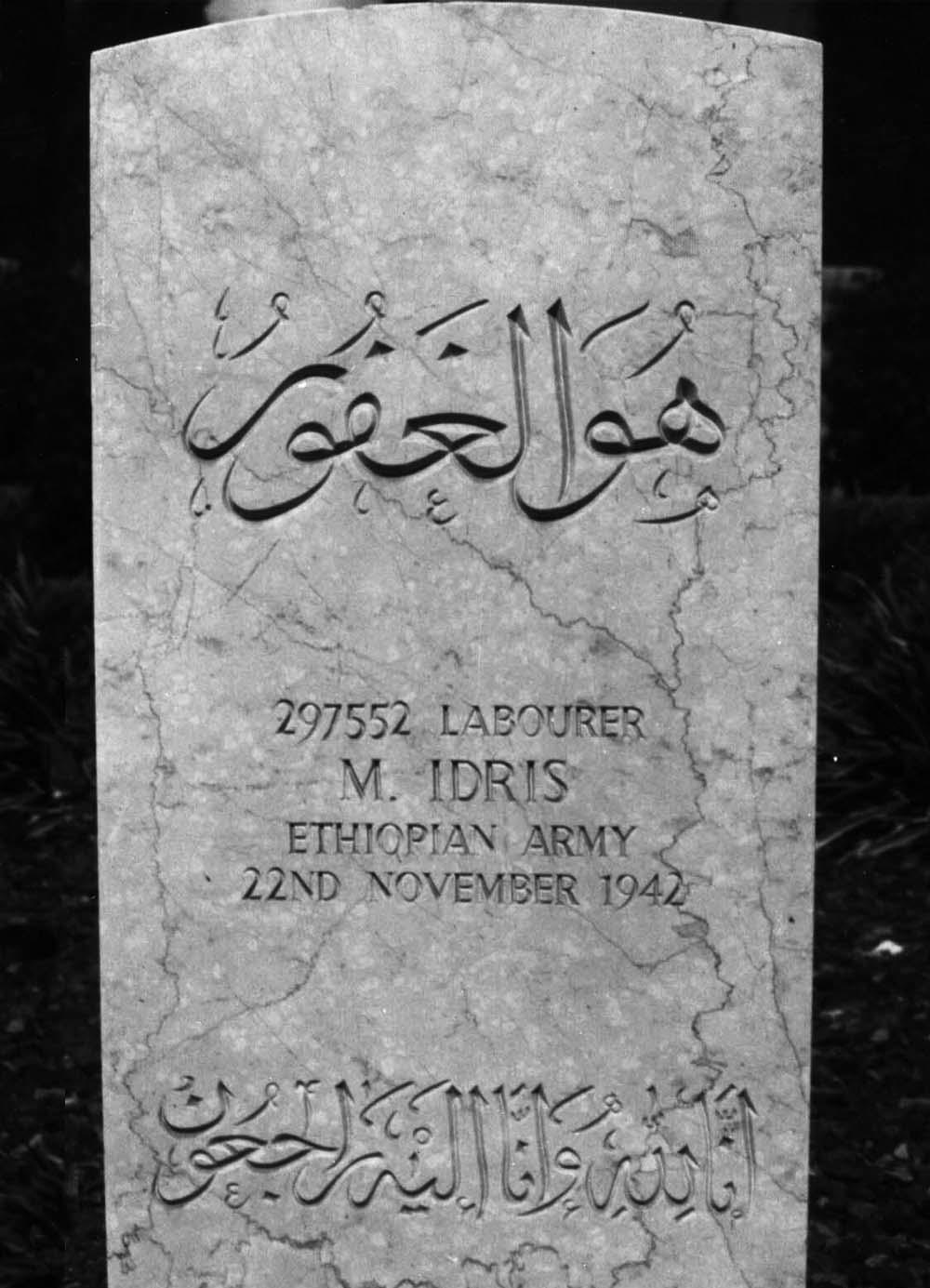

Religious Emblems

Symbols for all the major religions feature on our headstones, the most common being the Christian cross with over one million occurrences across both World Wars. However, this does not represent the number of confirmed Christian casualties, because where the religion was unknown the cross was used as a default emblem. Some Christian denominations were also concerned that only one style of cross was used.

Many headstones have no religious symbol by request. Whether this was motivated by atheism, non-conformism or another reason was never recorded, and therefore can only be speculated upon.

A ‘Final Verification’ form for a Jewish soldier, with the personal inscription “Deeply mourned by sisters, brothers and friends”. The line break in red ink has been added by a Commission employee. © CWGC.

Personal Inscriptions

Personal inscriptions provide the most intimate insight into those lives lost and those forever changed by the war. Yet they were initially limited to 66 characters, and a fee of 3½ pence per letter was charged for British Army casualties. The intention was that families would appreciate being able to practically contribute to a loved one’s commemoration, but the Commission soon faced accusations of hypocrisy because only the wealthy could afford a substantial inscription. Although we still engraved inscriptions if a payment wasn’t forthcoming, many people were deterred from writing one.

There are over 229,000 personal inscriptions for First World War graves. Ranging from literary and Biblical quotations to hymns, from meditations on abstract virtues to informal addresses to the dead, they offer a tantalising glimpse into the post-war process of grief.

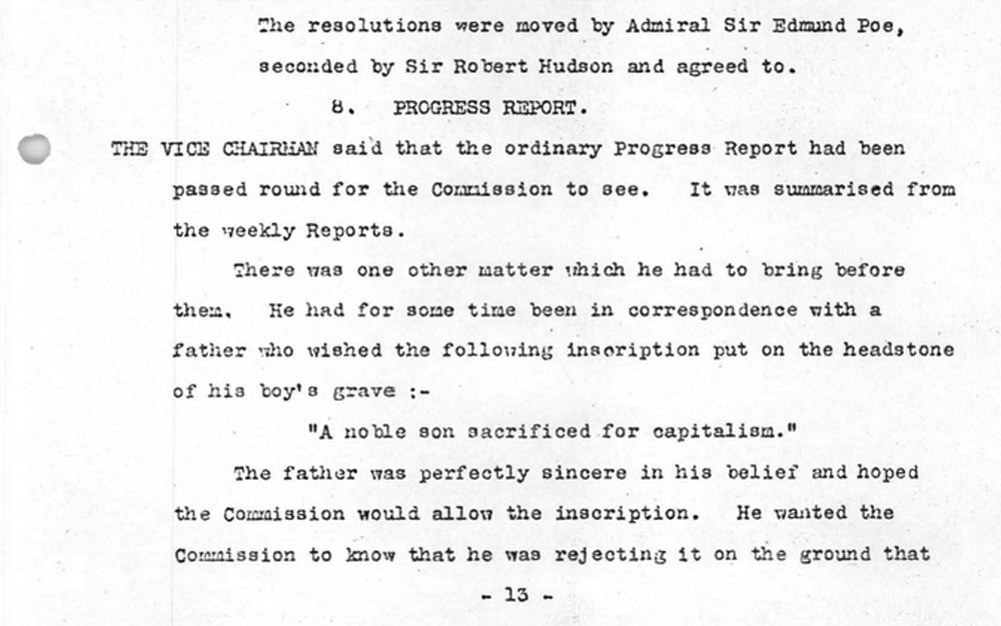

Committee minutes detailing rejected and accepted personal inscriptions. © CWGC.

However, the Commission had the right to veto inflammatory inscriptions. Several Committee minutes include debates over these controversial submissions, such as “A NOBLE SON SACRIFICED FOR CAPITALISM”. Interestingly, several were permitted that suggest the futility of war, indicating the liberal attitude the Commission tried to adopt when dealing with the delicate issue of loved ones’ sole means of expression.

Today the CWGC continues to recover bodies from former battlefields, reburying them with dignity and honour. When identification is possible, descendants are asked to provide a personal inscription for the headstone that will accompany a formal burial.

International differences

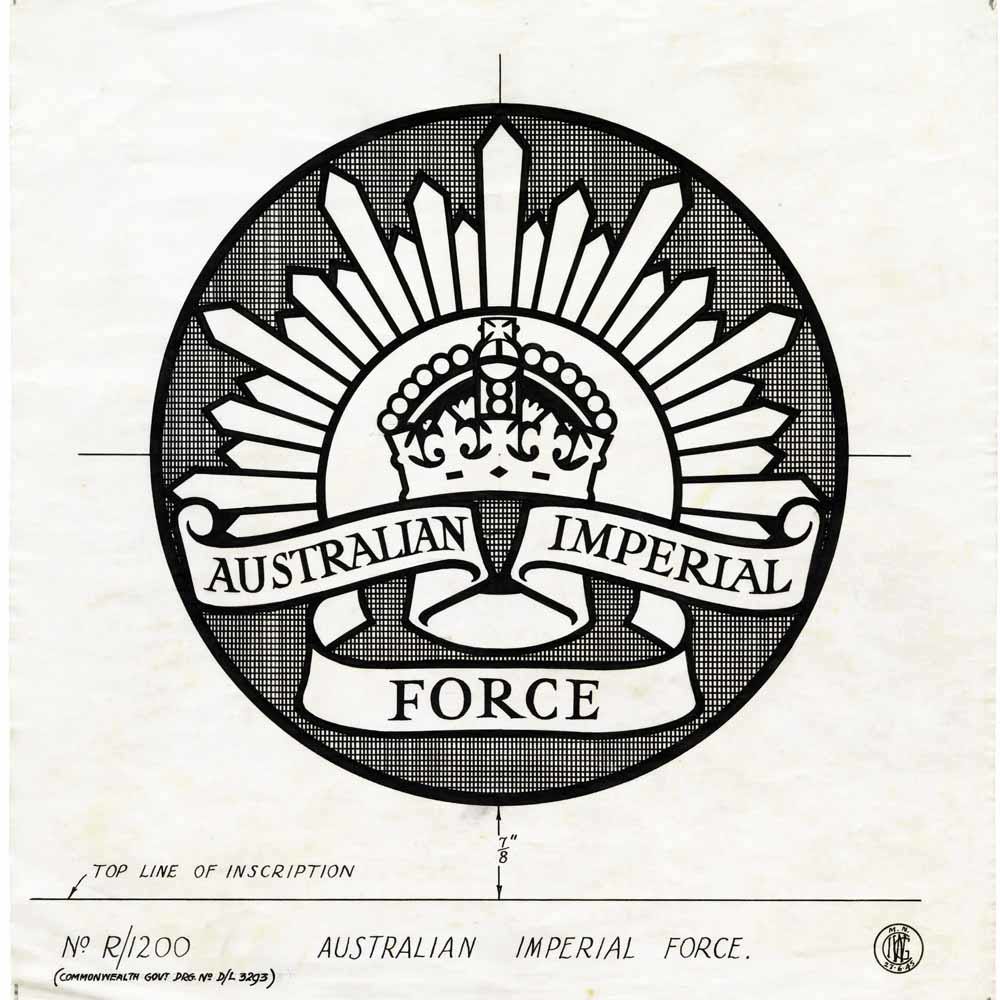

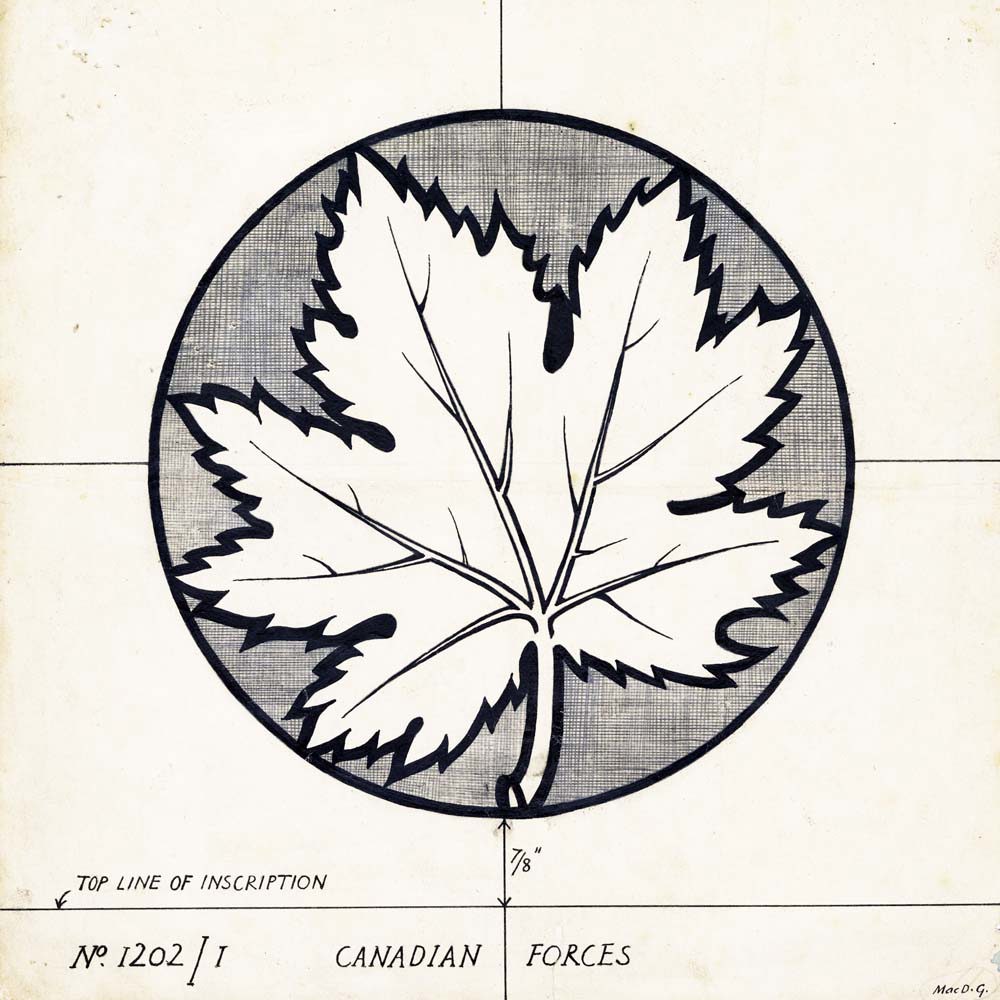

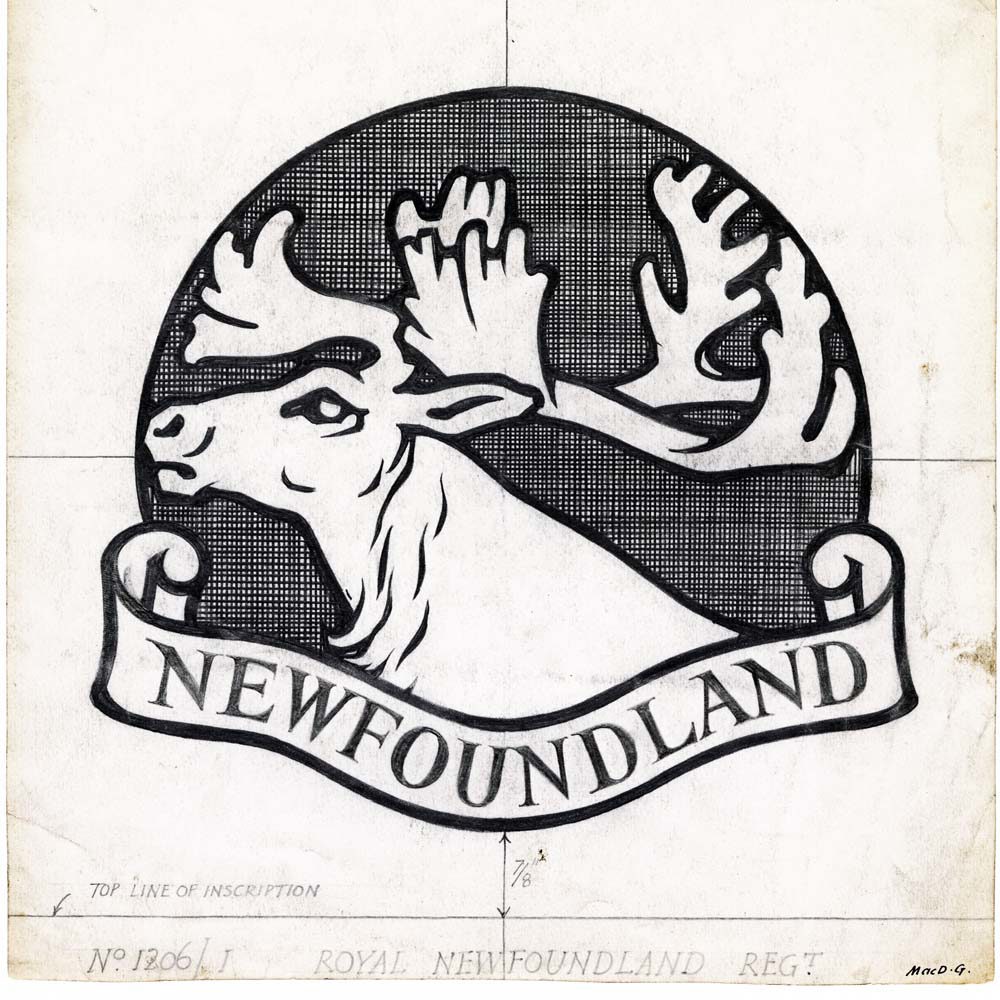

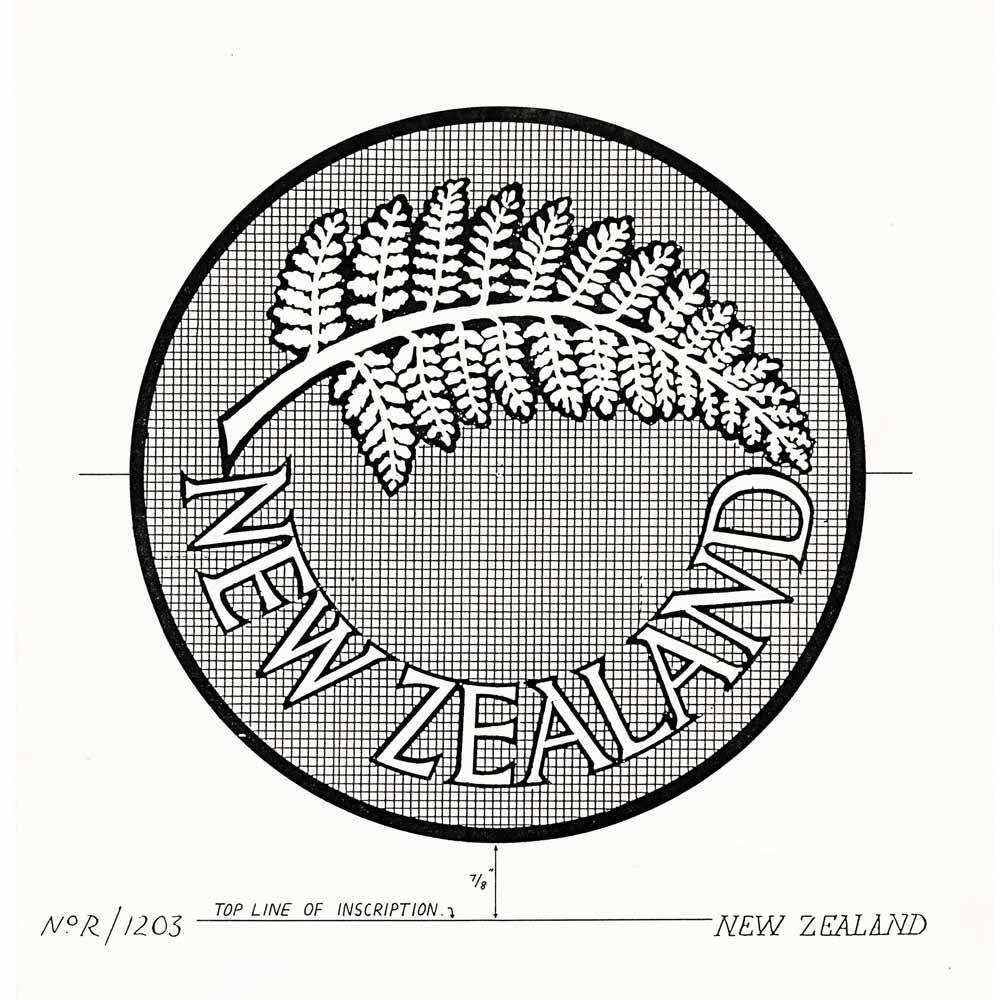

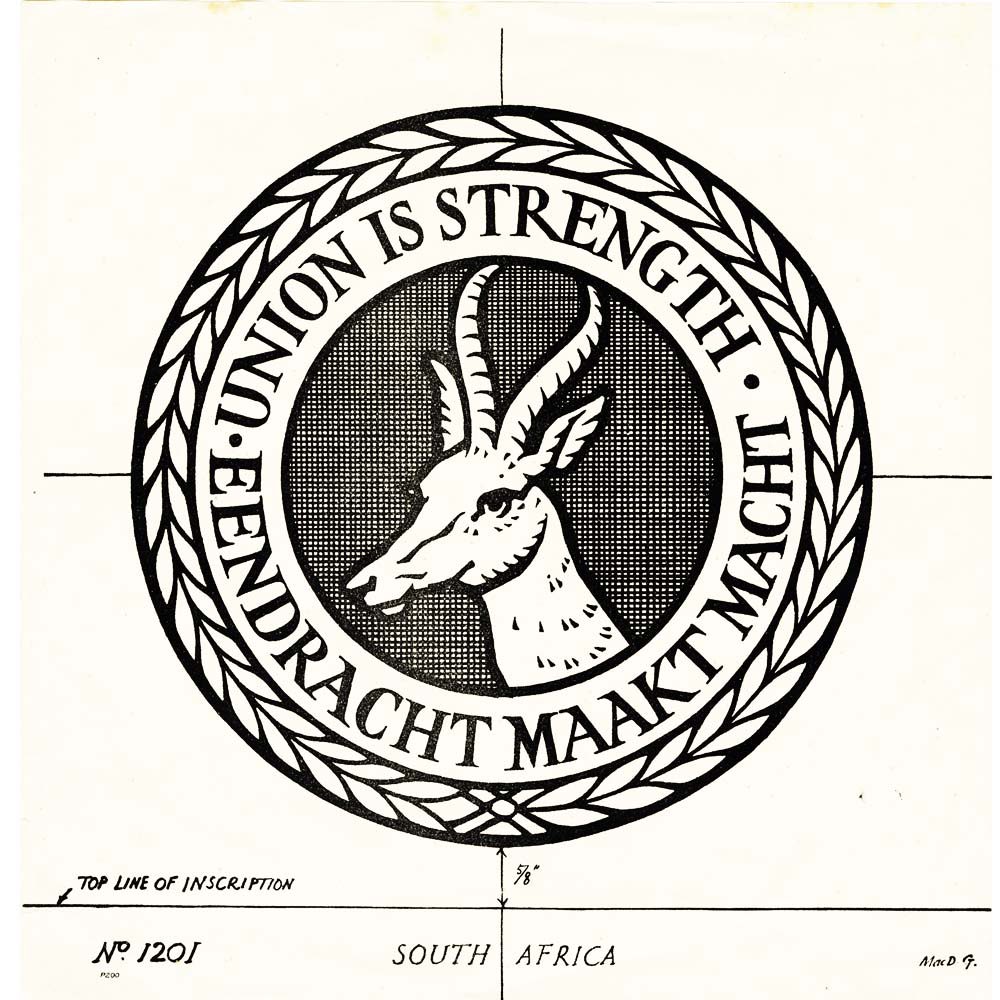

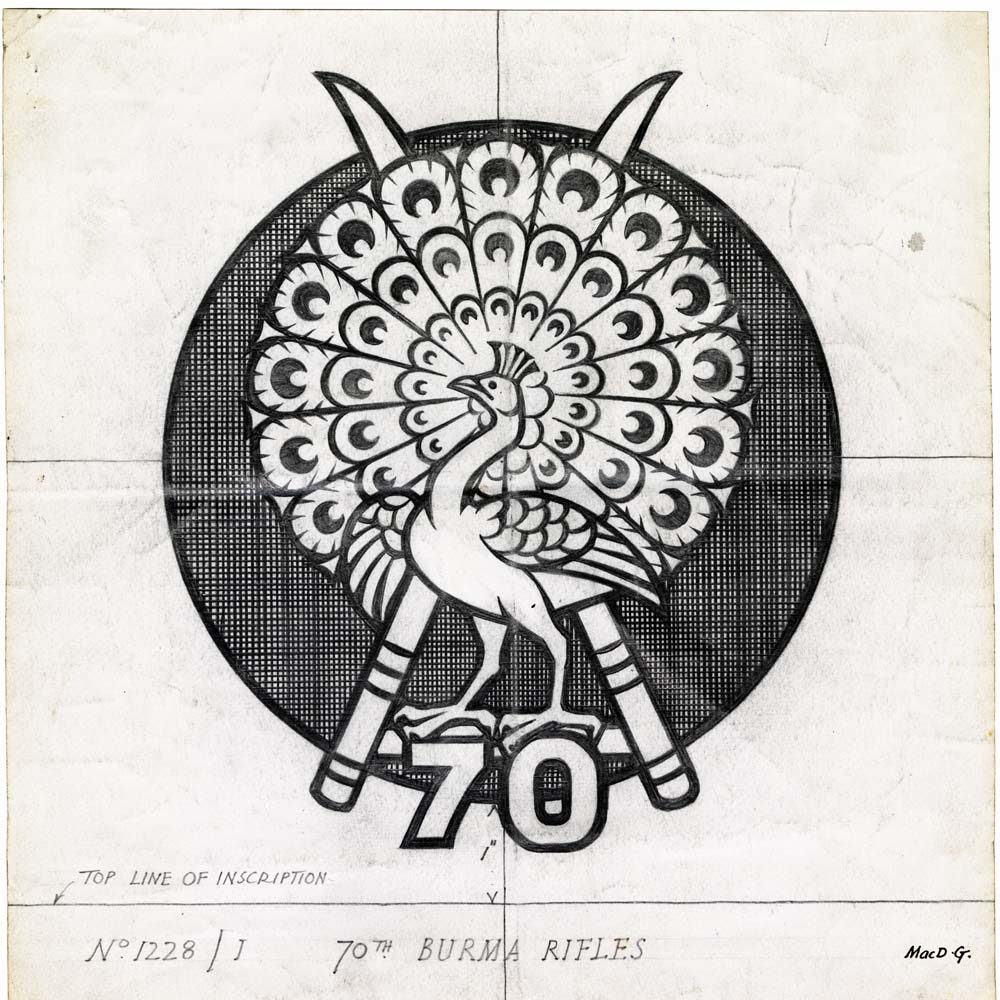

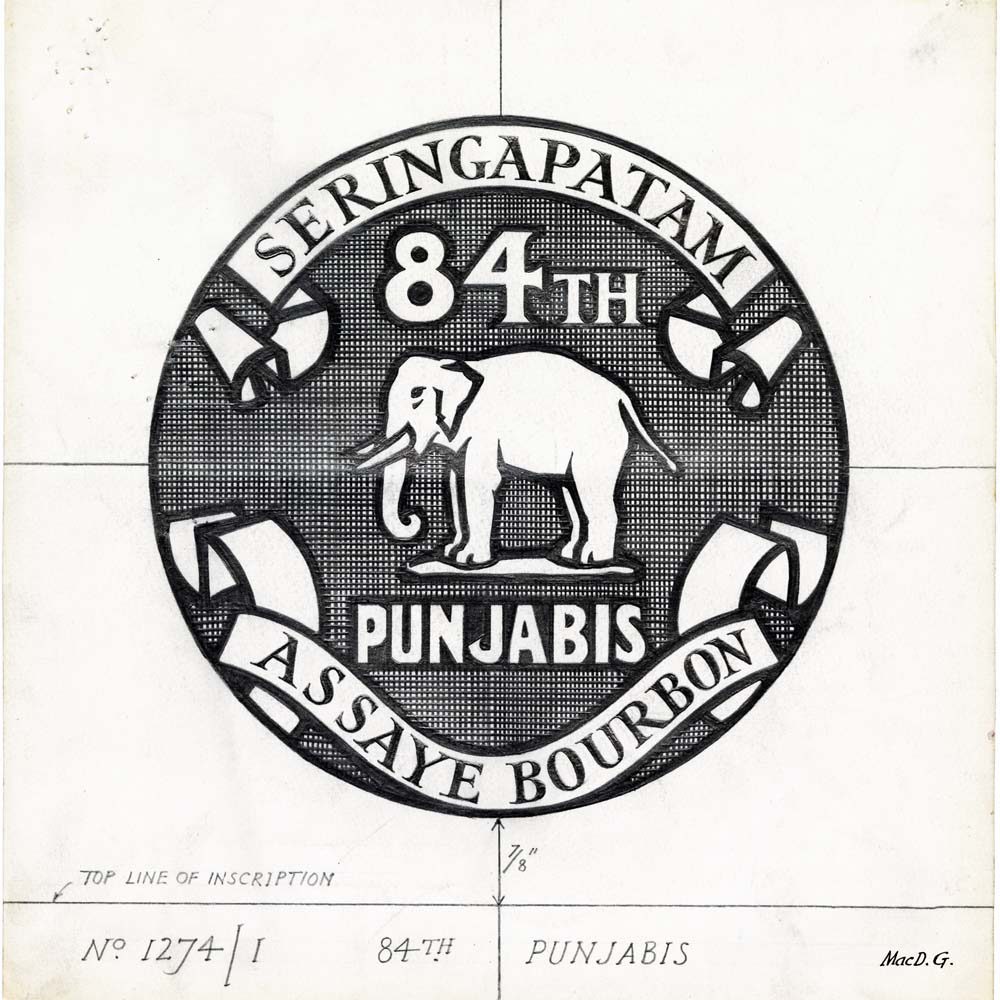

Pages from the ‘DGRE Technical Instructions’ pamphlet, rev. 1 February 1918. © CWGC.

Inevitably, there were differences of approach between the representatives of the British Empire’s ‘Dominions’ – Australia, Canada, Newfoundland, New Zealand and South Africa. Each had their own autonomous governments and arguably emerged from the war with a greater sense of national rather than imperial identity. India and other colonies, meanwhile, were represented by British government ministers at Commission meetings. Differences in religion and custom in India complicated the principle of uniform commemoration and the practicalities of burial itself. Consequently, a range of distinct policies and designs emerged through lengthy negotiation.

Burial

Meeting minutes of the Indian War Graves Committee, 20 March 1918. © CWGC.

The Directorate of Graves Registration and Enquiries (DGRE) – a military forerunner of the Commission tasked with searching for the dead – issued instructions on how to bury people of different faiths and nationalities. It included general advice like using a stake instead of a cross as a temporary grave marker, but also addressed specific burial rites. Regarding Chinese plots, for example, “The ideal site to secure repose and drive away evil spirits is on sloping ground with a stream below”.

Hindu cremation

At the Commission, an ‘Indian Graves Committee’ was established to ensure proper consultation on the distinct requirements for different religious groups; issues of exhumation and cremation were particularly debated.

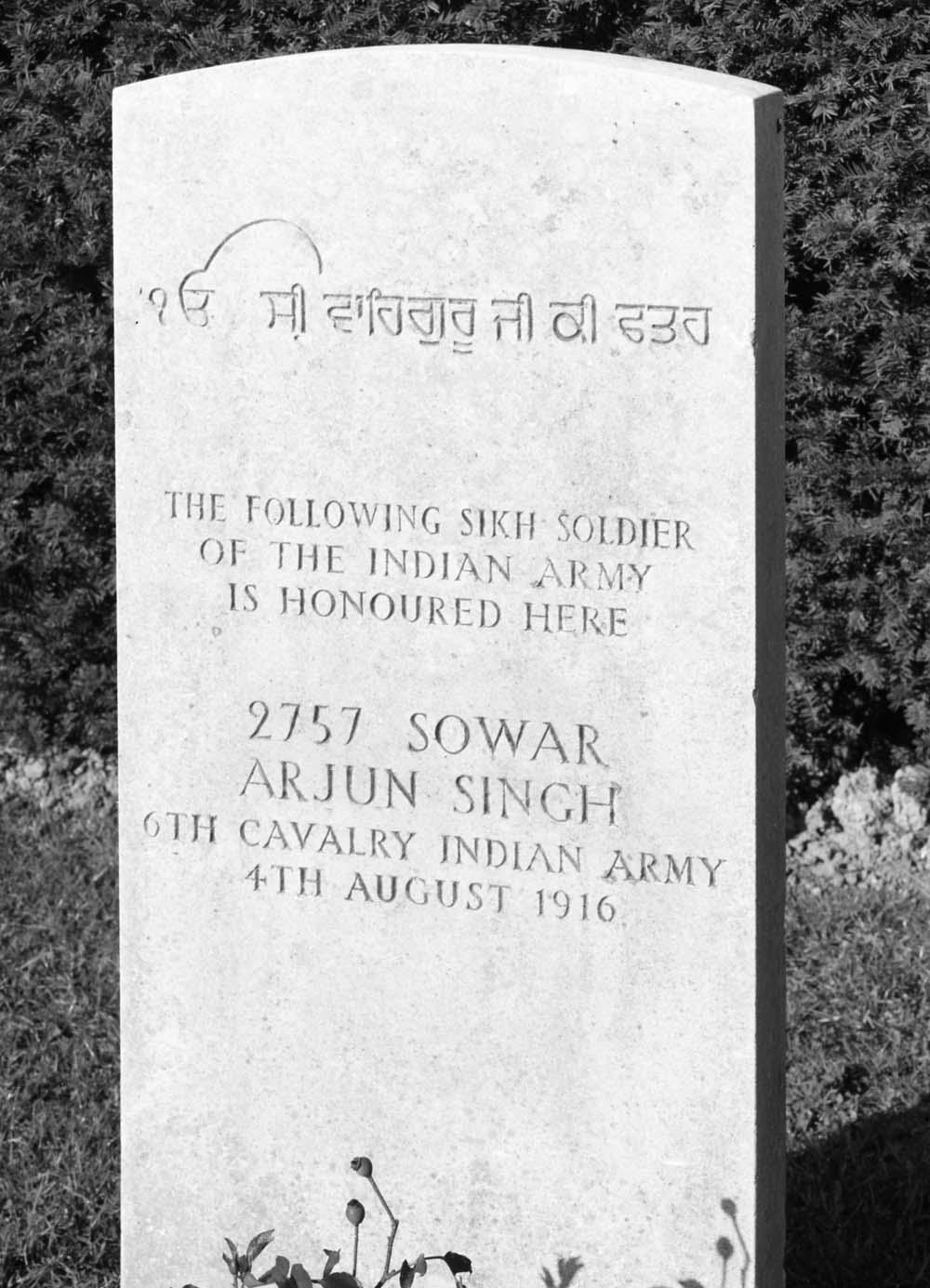

Headstones

Unlike Britain, the Australian and Canadian governments elected to cover the cost for personal inscriptions. Meanwhile, the New Zealand government banned personal inscriptions altogether, believing they contravened the principle of equality.

There are more noticeable differences between each nation’s headstones, too. While British and Indian Army casualties have their regimental badges carved into the stone, each Dominion has its own national emblem.

The national emblems of Australia, Canada, Newfoundland, New Zealand and South Africa are shown below. Also shown are several regimental emblems for the Indian Army. The artwork was created by the graphic designer Leslie MacDonald Gill. © CWGC.

Headstones could appear in different languages. We even have Chinese headstones honouring members of the Chinese Labour Corps (CLC) – volunteers who performed vital support roles on the Western Front. CLC workers were consulted on the traditional Chinese proverbs used on the headstones, including ‘A GOOD REPUTATION ENDURES FOREVER’ and ‘A NOBLE DUTY BRAVELY DONE’. Due to the intricacy of Chinese characters, it was felt that only CLC labourers could engrave the headstones, in what was described as “a work of love and not of finance”.

A member of the Chinese Labour Corps engraving a headstone for Noyelles-sur-Mer Cemetery, c.1919-20. © IWM Q100881.

Memorials

Each Dominion took a different approach to memorials: New Zealand opted for several small memorials spread geographically according to where their troops had fought, while Canada chose one enormous structure – the Vimy Memorial – to commemorate all its missing soldiers in France. South Africa had a national memorial at Delville Wood, but names of the missing were often listed alongside British names on memorials across the Western Front – the most famous being Thiepval Memorial.

Exceptionally, the Australian Commissioner argued that equality of treatment meant everyone who had died should have a marked grave, regardless of whether a body lay in it. This idea of ‘dummy graves’ was voted down, with Rudyard Kipling declaring “It gives me the creeps”.

Chunuk Bair New Zealand Memorial (1925)

One of four memorials erected to commemorate New Zealand soldiers who died on the Gallipoli peninsula and whose graves are not known. It bears 849 names.

Delville Wood South African National Memorial (1926)

Another Herbert Baker design, this honours all South African personnel who died during the war – totalling around 10,000. Unlike other memorials on the Western Front, this one has no names inscribed on it; many of them instead feature on scattered ‘battlefield memorials’ to the missing alongside British names.

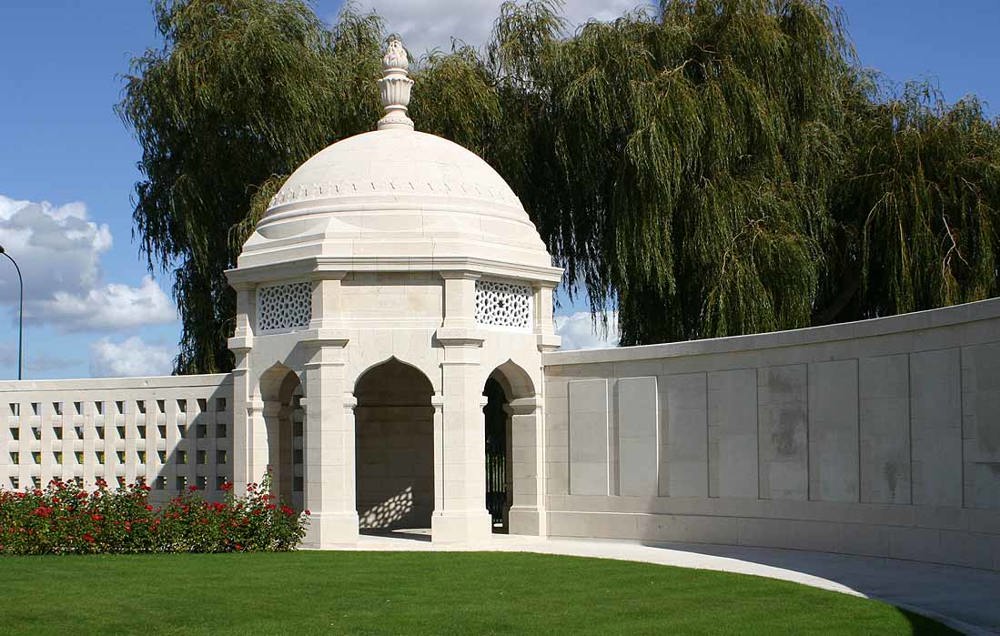

Neuve-Chapelle Indian Memorial (1927)

This memorial to the missing honours over 4,700 Indian soldiers. It was designed by Sir Herbert Baker, and the central column bears the same inscription in English, Urdu and Gurmukhi: “God is One, His is the Victory”.

The Menin Gate (1927)

Created by Blomfield, the Menin Gate is dedicated to those of every nationality except New Zealand who died in Belgium and have no known grave. It contains over 54,000 names.

Thiepval Memorial (1932)

One of Lutyens’ most famous designs, it commemorates over 72,000 missing servicemen of the British and South African armies who died in the Somme region between 1915 and March 1918.

Canadian National Vimy Memorial (1936)

Commemorates all missing members of the Canadian forces in France during the First World War. A competition to design the memorial was held in Canada, and won by non-Commission architect Walter Seymour Allward.

Equality for all

The fighting took no account of rank or class, and members of the social elite were among the dead. The sons of the Prime Minister Herbert Henry Asquith and the Labour leader Arthur Henderson died on the same day during the Battle of the Somme, while the brother of Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon – the future Queen Consort and Queen Mother – was killed at the Battle of Loos in 1915.

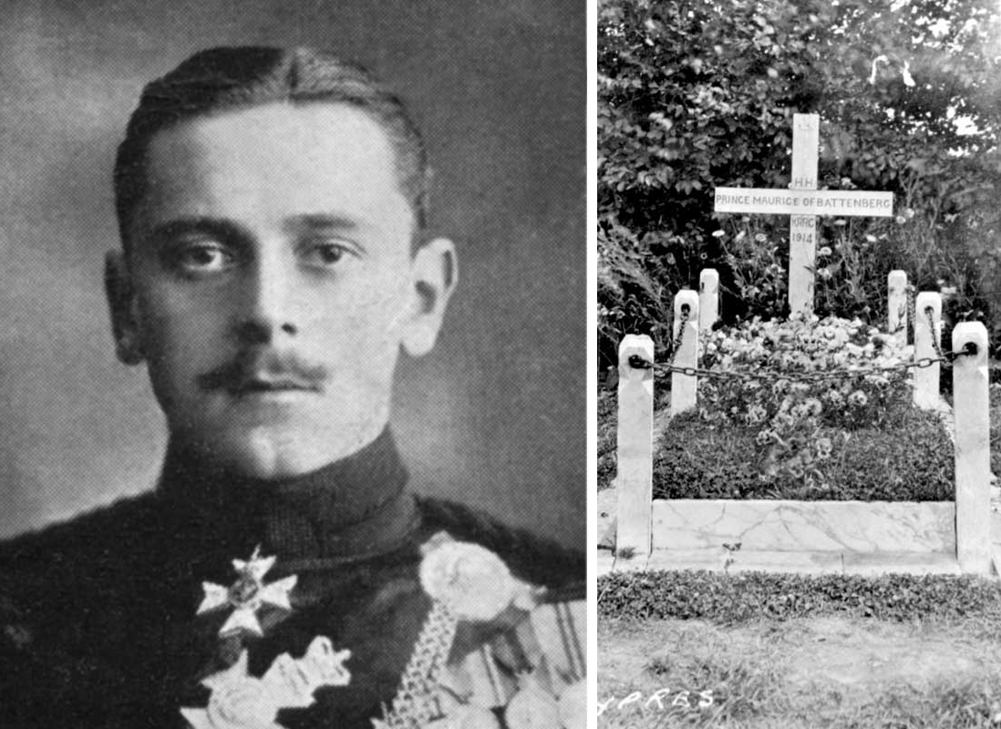

The highest-status aristocrat to die was Prince Maurice of Battenberg, the youngest grandchild of Queen Victoria. The subsequent fallout over his place and manner of commemoration severely tested the Commission’s tenet of equality.

Killed at Zonnebeke in October 1914, Battenberg was buried in Ypres Town Cemetery among civilian graves and scattered war graves. His mother, Princess Beatrice, ordered an imposing granite cross for his headstone. This contravened the standard Commission design, but Beatrice felt that the Prince’s royal status should be recognised. Thus began a tense back-and-forth between Fabian Ware and the Princess’ representatives over how to proceed.

Prince Maurice Victor Donald of Battenberg by Bassano, 1911. © National Portrait Gallery x79911. The original wooden cross marking the Prince’s grave, c.1922 © CWGC.

“I had hoped that Princess Beatrice would have been ready to give a lead in this question of equality of treatment”

Fabian Ware on Princess Beatrice, 1920

A frustrated Ware wanted Beatrice to be a powerful example of equality in action, but she held her ground. She was reportedly “exceedingly angry” at the idea of a separate location for the cross, instead requesting the moving or repatriation of Maurice’s body. By 1925 newspapers reported that Maurice would soon be receiving a Commission headstone, but Beatrice insisted that it be accompanied by her granite cross. Ware wrote again to change her mind, emphasising the “wonderful impression” that would be created if she democratised the headstone.

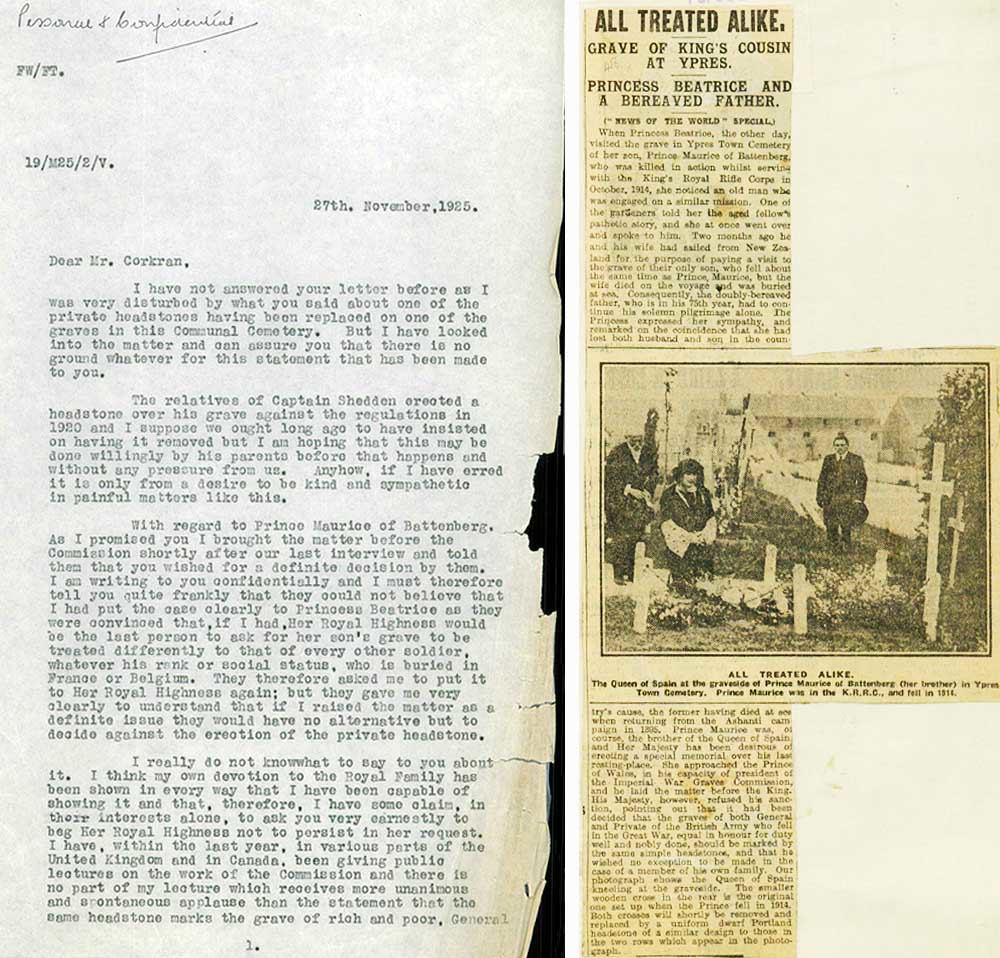

Letter from Fabian Ware to Sir Victor Corkran, Comptroller of the Princess’ household, 27 November 1925. © CWGC ‘All Treated Alike’, News of the World, 19 July 1925. © CWGC.

The controversy rumbled on until 1932, when Beatrice agreed to Maurice being commemorated in the same way as his comrades. But notably this was only at the request of his regiment – not the Commission. His headstone bears the inscription: “GRANT HIM WITH ALL THY FAITHFUL SERVANTS A PLACE OF REFRESHMENT AND PEACE”.

The original headstone, designed by Princess Beatrice and the final Commission headstone marking his grave. © CWGC.

Battenberg’s case showed that no one could escape the effects of war – a fact the Commission’s staff knew only too well. For many, their work was a means of confronting and overcoming the trauma of losing loved ones or fighting themselves. Read on to learn more about the personal anguish at the heart of the Commission in its early years.