25 March 2024

Legacy of Liberation: Kohima, Imphal and the Turning Point in the Far East

80 years ago, the Battle of Kohima and Imphal marked the turning point in the Far East campaign. Read on to discover the story and how the battle’s fallen are commemorated.

The Battle of Kohima & Imphal

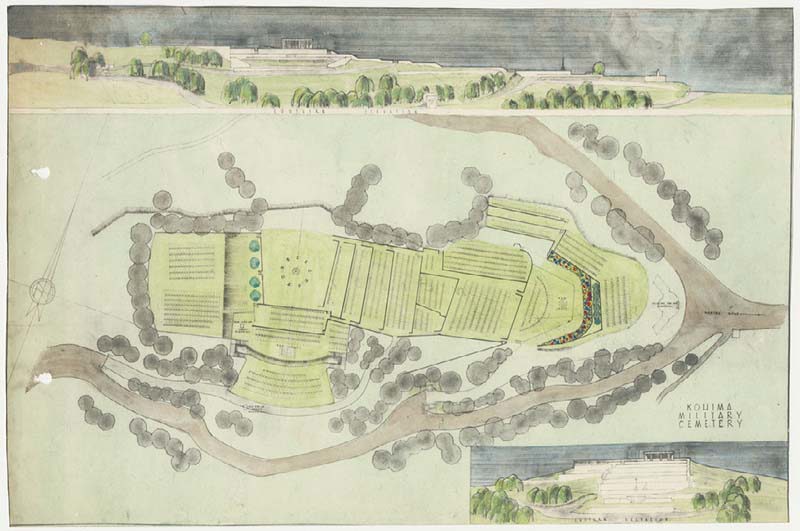

A war cemetery and a tennis court

Image: Kohima War Cemetery with the famous tennis court still visible.

On Kohima’s old Garrison Hill, overlooking the bustling provincial capital, lies a spot of peaceful tranquillity. Roses bloom in season, dotting the lush, well-kept grass with eye-catching spots of delightful colour.

Ribbons of CWGC headstones lay across the greenery, set atop small plinths, each proudly bearing the name of a fallen Commonwealth serviceman. Tiers and terraces hug the landscape, perfectly integrating the cemetery with its beautiful surroundings.

Look closely, and you’ll spot the outline of a tennis court etched into the soil. It sits beneath a central stone shelter, atop which stands the iconic Commonwealth War Graves Cross of Sacrifice.

A tennis court seems like an odd feature of a Commonwealth War Graves war cemetery. But at Kohima, it’s integral to the character and history of this storied location.

For it was here, on the ground where the cemetery lies, thousands of British and Indian servicemen fought one of the most desperate battles of the Second World War’s Far East Campaign: The Battle of Kohima and Imphal.

Britain’s greatest battle?

In 2015, the National Army Museum launched a poll to find Britain’s greatest battle.

Storied victories like Trafalgar, Agincourt, Waterloo and the Battle of Britain, or world-changing events like D-Day and the Battle of Hastings, all fell

behind the battle of Kohima and Imphal.

The five-month clash on the Indian-Burmese border has entered legend as one of the most decisive battles of the Second World War and a definitive Commonwealth victory.

But as the cemeteries and memorials that commemorate the war dead of the battle attest, victory was not without cost.

Commemoration at Kohima and Imphal

The war cemeteries in Kohima and Imphal mark the ferocity and difficulty of fighting in this part of the world.

Combat covered vast areas and, while Kohima and Imphal were more concentrated, the terrain was almost as hostile as the opposing army. Dense, verdant jungles, exposed clearings, rushing rivers, plunging valleys and rocky mountainsides all played host to fighting.

Grave Registration Units (GRUs) worked to bury and record the resting places of the dead. Such was the scale of their task that it wouldn’t be completed until the late 1940s. Then, Commonwealth War Graves took control of the Kohima and Imphal cemeteries and memorials and maintain them to this day.

Kohima War Cemetery

Kohima War Cemetery is perhaps the most iconic of the CWGC’s cemeteries in the Far East. The first burials were made here during the fighting in 1944, and it was decided soon afterwards that a permanent cemetery should be built.

Over the following years isolated burials were brought from across the surrounding area, and plots for different religions were created.

In August 1948, the cemetery passed into the care of the War Graves Commission. Colin St. Clair Oakes incorporated the unique features of the site into his design, including the tennis court across which the battle had raged, and the only cherry tree to have survived the battle.

Today, more than 1,400 Commonwealth servicemen are buried here. More than 900 Hindu and Sikh soldiers who were cremated in accordance with their faith are commemorated on the Kohima Cremation Memorial within the cemetery.

There are also many memorials placed by comrades and veterans in memory of those buried here. Inscribed on the 2nd Division Memorial is the famous Kohima Epitaph:

"When you go home, tell them of us and say, for your tomorrow, we gave our today."

Imphal War Cemetery

This cemetery was begun during the war and more than 500 servicemen were laid to rest here. After the fighting was over the Imphal plain and the surrounding mountainous jungles were searched and the graves and remains of 1,000 other personnel were brought here for burial.

The cemetery was designed in the style of a Mughal garden, using geometry and water to create an atmosphere of calm reflection. The entrance is a late example of the Indo-British Imperial style developed in the 19th Century.

Today, Imphal War Cemetery is the final resting place of more than 1,600 Commonwealth service personnel, almost 140 of whom remain unidentified.

Imphal Indian Army War Cemetery

This cemetery was begun during the war, and today almost 1,700 Commonwealth service personnel are buried or commemorated here, more than 200 of whom remain unidentified.

Many of those who died at Imphal belonged to the Sikh, Hindu, and Muslim faiths. Muslims were laid to rest in Imphal Indian Army War Cemetery, while Sikh and Hindu soldiers were cremated in the cemetery in accordance with their faith.

They are commemorated by name on the Imphal Cremation Memorial, which stands at the heart of this cemetery.

What was the Battle of Kohima and Imphal?

Image: West Yorkshire Regiment soldiers & 10th Gurkha Rifles, Imphal, 1944 (© IWM)

The Battle of Kohima and Imphal was fought between 8 March and 18 July 1944 between Great Britain and India and Imperial Japan.

For many, Kohima and Imphal mark the turning point of the Burma Campaign fought in present-day Myanmar.

In his book Japan’s Last Bid for Victory, historian Robert Lyman wrote “Kohima/Imphal was one of the four great turning-point battles in the Second World War, when the tide of war changed irreversibly and dramatically against those who initially held the upper hand”.

Background to Kohima & Imphal

December 1941 saw Imperial Japan launch a series of daring attacks across Asia and the Pacific.

Hong Kong, Singapore, and Burma fell in rapid succession.

Burma’s conquest in particular set alarm bells ringing. The nation borders India and the threat of an invasion became an almost existential fear for India’s administrators.

The fear spread to the general public too. India’s free press had widely reported Japanese atrocities committed throughout Asia, especially at Nanking in China.

A full-scale invasion of India could lead to more of the same and would be potentially catastrophic.

The Fourteenth Army

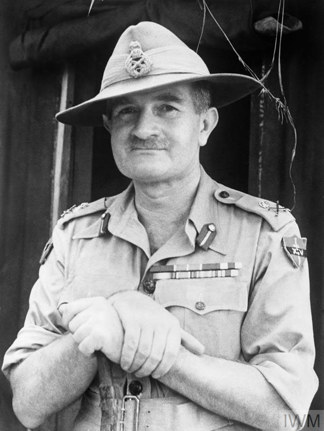

Image: General William Slim, commander of Fourteenth Army (© IWM)

Image: General William Slim, commander of Fourteenth Army (© IWM)

By winter 1942, what remained of the Commonwealth army in the Far East was recovering in the north-eastern Indian provinces of Nagaland and Manipur, on the border with Burma.

Morale was low but their enigmatic commander, General William Slim, was undeterred. He set about regrouping, retraining, and resupplying his men, intending to return to Burma at the earliest opportunity.

In 1943, Slim’s force was renamed the Fourteenth Army. It was one of the most diverse in history, with African, Indian, Gurkha and British formations.

Soldiers from the Gold Coast (present-day Cote D’Ivoire) and Sierra Leone, Uganda, and Kenya, worked alongside those from across undivided India, and the United Kingdom.

Over the next two years, they trained tirelessly to become a formidable fighting force, specialising in jungle warfare.

Battle of the Admin Box

Image: Sikh troops at the Battle of the Admin Box (Wikimedia Commons)

The Japanese knew that Allied and Commonwealth strength was building in India. They would soon have to act if they wanted to land a knockout blow.

While it worked up plans for the main invasion of India, the Japanese high command launched a diversionary offensive in Arakan.

Clashes soon erupted along the India-Burma border. One of the most famous took place between 5-23 February 1944 in an area of the Arakan called the Admin Box.

The Admin Box was a small staging area manned by a rag-tag bunch of clerks, drivers, muleteers, and base troops, reinforced by troops from Yorkshire and the tanks of the 26th Dragoons.

Facing them were some of Japan’s best infantry. Using their familiar infiltration tactics, the Japanese Army managed to cut the roads supplying the Admin Box and surround the Indian and British troops stationed within.

Fighting was brutal and up close, but, as they were able to be reinforced and resupplied by air, the Commonwealth soldiers stood their ground. The Japanese were at the end of their supply lines and soon began to run out of food and ammunition.

By 22 February, with munitions, men and morale running low, and food and water running scarce, the Japanese Army was forced to retreat.

While the British and Indian units took more casualties, some 3,500 killed, missing, captured, or wounded, the toll on the Japanese was more than 3,000 killed, 2,200 wounded, and 65 precious fighter aircraft lost.

Admin Box showed that, with enough skill, stubbornness, and airborne supplies, the Japanese Army, which had looked invincible for years, could be decisively beaten.

Operation U-Go and the Invasion of India

The Japanese were well aware of the Commonwealth and Allied forces gaining strength in India and China. Intending to destroy the threat, the Japanese launched Operation U-Go, the invasion of India.

After fierce clashes on the border in February 1944, the main Japanese force, 85,000 strong, crossed the Chindwin River on 8 March and poured into India.

The Battle of Imphal

Image: British soldiers search for Japanese snipers, Imphal, c.1944 (© IWM)

By April, the Japanese had reached Imphal.

The town lies on a vast plain, surrounded by mountains and jungle, and here the bulk of the Fourteenth Army made their stand.

The Japanese moved quickly to surround the defenders but, unlike in previous clashes, the Commonwealth troops battled on, resupplied from the air.

The fighting was brutal and confused, and groups of men could be completely isolated for days, fighting for survival.

Jemadar Abdul Hafiz VC

Image: Abdul Hafiz (Public domain)

Image: Abdul Hafiz (Public domain)

Born on 1 July 1918, in the Rohtak district of the Punjab, Abdul Hafiz served with the 9th Jat Regiment in the British Indian Army during the Second World War.

On 6 April 1944, during the Battle of Imphal, he led a counter-attack against a Japanese position.

Although twice wounded leading the advance, he charged a machine-gun, killing the crew.

He continued at the head of his men until finally collapsing. His last words were to encourage his soldiers on.

For his inspirational leadership and courage, he was posthumously awarded the Victoria Cross, the highest award for bravery.

He is buried in Imphal Indian Army War Cemetery.

The Battle of Kohima

Image: British infantry hold an improvised machine gun position at Kohima (© IWM)

60 miles north of Imphal, a small Commonwealth garrison held the town of Kohima, at the highest point of the pass through the impenetrable mountain jungles to Dimapur. If Kohima fell, Dimapur would follow, and the vital supplies for the defenders of Imphal would cease.

On 3 April, a Japanese force of 15,000 attacked Kohima.

Of the 2,500-strong garrison at Kohima, only half were combat troops. Pushed back in desperate and bloody fighting, they held out on Kohima Ridge. Before the war, the British Deputy Commissioner had lived here, and his house and tennis court became the scene of a brutal hand-to-hand struggle.

The once-peaceful ridge was transformed into a wasteland of blasted tree stumps and shell holes.

After two weeks of constant fighting the garrison held only 350 square metres of ground near the tennis court, and the situation was desperate. Few Commonwealth soldiers remained unwounded, many were almost starving, and all were severely dehydrated. The end seemed near.

Lance Corporal John Pennington Harman VC

Image: Grave marker of John Harman VC

Image: Grave marker of John Harman VC

John Pennington Harman was born on 20 July 1914, at Beckenham in Kent, the eldest child of millionaire businessman Martin Coles Harman.

In 1925, his father - an avid nature lover - purchased Lundy Island in the Bristol Channel. In November 1941, John was called up for service and in early 1943 he was sent to India, eventually serving with the 4th Battalion of the Queen’s Own West Kent Regiment.

In 1944, he was part of the Kohima Garrison when the Japanese attacked. John led a platoon during the desperate fighting and twice went out alone to attack enemy positions. The second time he was badly wounded, and lay dying in no-man’s land.

His company commander, Major Easten, braved enemy fire to bring him in. He called for stretcher bearers, but John said “Don’t bother Sir….I got the lot. It was worth it” and died in Easten’s arms.

John was 29 years old.

For his actions during the Battle of Kohima, John was posthumously awarded the Victoria Cross. His father collected the VC from Buckingham Palace and carried the medal with him for the rest of his life.

John is buried in Kohima War Cemetery. Upon his grave marker are inscribed the words, ‘Of Lundy, The Earth is the Lord’s’.

Victory at Kohima

Image: Garrison Hill after the fighting had stopped at Kohima (© IWM)

At dawn on 18 April, the exhausted Kohima garrison prepared to make their last stand. In the enemy trenches just a few metres away they could hear the Japanese massing for their final attack.

At that moment shells began falling on the Japanese positions and tanks of the relieving force could be seen arriving. The garrison was saved from annihilation and Kohima was secured.

The Japanese, however, were far from defeated, and they fought bitterly to hold the many ridges and hills surrounding Kohima. After four weeks the Japanese soldiers were starving and they were finally forced to withdraw in mid-May. The Battle of Kohima was over.

Captain John Randle VC

Image: Victoria Cross Winner John Randle (Public domain)

Image: Victoria Cross Winner John Randle (Public domain)

John “Jack” Randle was born in India on 22 December 1917. In 1920, his family moved to England and Jack was sent to the Dragon School and Marlborough College, before going on to study law at Merton College, Oxford. In May 1940, Jack was commissioned as a Second Lieutenant in the Royal Norfolk Regiment. A year later he married Mavis Ellen Manser, and they had a son, Leslie.

In 1944, John was serving in India with the 2nd Infantry Division. Following the Japanese attack at Kohima the Division fought its way through the mountain pass to relieve the Kohima Garrison. Over the next four weeks they fought to drive the Japanese back.

During the battle John performed several deeds of incredible bravery.

He had been badly wounded in the knee by a grenade but refused to be relieved. Despite the pain, he went into no-man’s land on 4 May and brought back several wounded comrades.

Two days later his company was ordered to take a Japanese position on a ridge which was heavily fortified and where several attacks had already failed.

John was hit several times during the advance but, undeterred, he charged a Japanese bunker. He threw in a grenade and then flung himself across the entrance to seal it. He was 26 years old.

He is buried in Kohima War Cemetery. Upon his grave marker are inscribed the words ‘Remembered by his devoted wife, only son Leslie John, Parents and Sisters’.

Victory at Imphal

Reinforcements from Kohima link up with the soldiers at Imphal (© IWM)

With the road to Dimapur secured, the defenders of Imphal linked up with reinforcements advancing from Kohima on 22 June.

Under constant air attack and with their supply lines mercilessly assaulted by Chindit forces and air strikes, the last Japanese attacks at Imphal launched in late June had no success.

On 3 July, after nearly five months of fighting, the surviving Japanese forces fell back. More than 8,000 Commonwealth servicemen were wounded, killed or missing, but of the 85,000 strong Japanese force that had crossed the Chindwin River in March, less than a third returned.

The battles had been fierce, but it was starvation and disease that had caused most of the Japanese losses. It was by far the worst Japanese land defeat of the war to that date.

Serjeant Hanson Turner VC

Image: A portrait of Serjeant Hanson Turner VC (Public domain)

Image: A portrait of Serjeant Hanson Turner VC (Public domain)

Hanson Turner was born in Hampshire on 17 July 1910, but grew up in Yorkshire. He was the second eldest of nine children. He attended St. Augustine’s School in Halifax and was a member of the Rhodes Street Boys’ Brigade. After leaving school Hanson got a job as a bus conductor.

In 1935, he married Edith Rothery, a local girl from Halifax, and in November 1938 they had a baby girl, Jean. Hanson was a keen gardener and supporter of Halifax Town AFC.

In 1940, Hanson enlisted in the Army, joining the Duke of Wellington’s Regiment. He was posted to India and served as a Serjeant during the Battle of Imphal with the 1st Battalion of the West Yorkshire Regiment.

On 7 June 1944, he led the defence of an important position against a determined Japanese night assault. Fighting alone with grenades, he returned for more ammunition five times. He was killed while charging a group of Japanese soldiers. For his courage he was posthumously awarded the Victoria Cross. He was 33 years old.

Hanson is buried in Imphal War Cemetery. Upon his grave marker are inscribed the words, ‘Well done, good and faithful servant, ever remembered’.

Aftermath and the advance into Burma

After their defensive victory, the Commonwealth forces planned a new offensive to clear the last Japanese forces from northern Burma and drive them south towards Mandalay and Meiktila.

Battling through the monsoon, and supplied from the air, troops of the Fourteenth Army now crossed the River Chindwin. After fierce fighting, Meiktila and Mandalay were captured in March 1945.

The route south to Rangoon lay open and in early May the city was taken.

The Japanese surrendered three months later.

Discover the Legacy Of Liberation with Commonwealth War Graves

The Legacy of Liberation marks the 80th anniversaries of several pivotal moments during the second world war. From Kohima and Imphal to the D-Day Landings, the Legacy of Liberation remembers these remarkable events.

Join us to mark these historic moments. Visit The Legacy of Liberation today to learn more.

Join us as we mark the 80th anniversaries of some of the most pivotal events of the second world war. From events to online resources, dicover the Liberation of Legacy today.

Liberation