12 February 2024

Tragedy in the Indian Ocean: The Sinking of the Khedive Ismail

80 years ago today, on 12 February 1944, Commonwealth forces suffered their largest loss of servicewomen in a single day in the Second World War. This is the story of the sinking of SS Khedive Ismail.

Sinking of SS Khedive Ismail

What was SS Khedive Ismail?

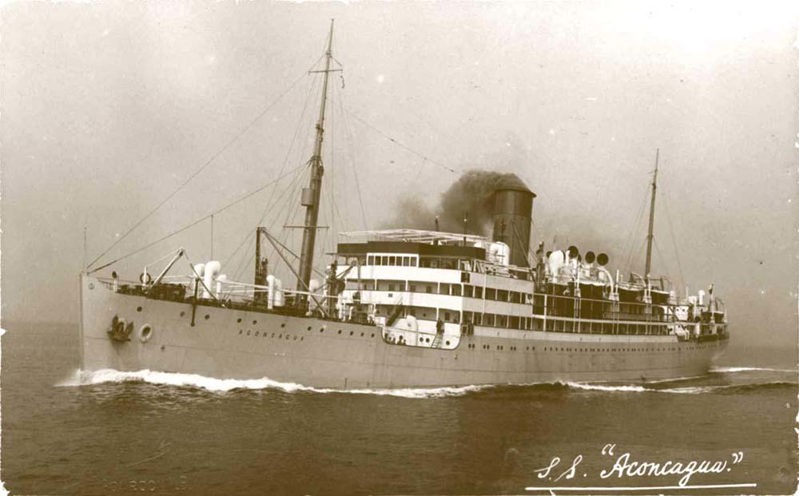

Image: SS Khedive Ismail sailing under her original name Aconcagua (Reddit)

SS Khedive Ismail was a troopship during the Second World War.

She was originally launched in 1922 under the name Aconcagua as an ocean liner. In her early service, Aconcagua ran the route Valparaiso-Panama-New York, ferrying passengers and cargo between Chile, central and north America.

In 1935, Aconcagua was sold to the Kedivial Mail Steamship and Graving Dock Company of Alexandria (KML), Egypt. She was renamed Khedive Ismail after Egyptian Khedive Isma’il Pasha who ruled from 1863-79.

She would continue to sail under the name Khedive Ismail for the rest of her career.

Khedive Ismail’s military service

The British Empire declared war on Nazi Germany in September 1939 and so began a period of acquiring ships for military purposes.

Khedive Ismail was acquired by the British Ministry of Transport alongside seven other KML ships, including her sister ship Mohamed Ali El-Kebir. Khedive was placed under the management of the British-Indian Steam Navigation Company.

She was converted into a troop ship and her tonnage was increased from 7,290 to 7,513.

Once up to full troop ship specifications, Khedive Ismail was assigned to the Indian Ocean, ferrying troops from across the Empire to bases in Egypt.

In August 1940, Mohamed Ali El-Kebir was sunk on her first troop voyage, highlighting the dangers faced by troop ships, even under escort as was the case with Mohamed Ali El-Kebir.

Khedive Ismail’s military service took her to ports all over the world, calling at Cape Town, Mumbai, Mombasa, Port Sudan and Port Said, travelling through the Suez Canal.

In April 1941, following the Axis invasion of Yugoslavia and Greece, Khedive Ismail was one of the troop ships assigned to Convoy AG 14 to evacuate 60,000 Commonwealth troops from the region.

The convoy came under attack by the German air force. Several ships were damaged and passengers wounded, and the destroyers HMS Diamond and Wryneck were sunk, but the convoy was able to reach Crete.

After that, Khedive Ismail spent the bulk of her operational life crisscrossing the Indian Ocean, carrying troops from ports up the African coast to India and Sri Lanka.

East African Military Nursing Service

As well as front-line units and logistics personnel, Khedive Ismail also transported medical personnel to where they were needed most.

One of the units transported by the troop ship was the East African Military Nursing Service (EAMNS).

The EAMNS was formed on 1 July 1940 under the auspices of the British Army’s East African Command.

It was a temporary colonial unit. Women enlisted in the EAMNS were to serve for the whole war unless they were discharged early.

Nurses were recruited locally and helped expand and solidify nursing operations in East Africa. Those recruited were drawn from the region’s private and civil sectors. Some had previous experience

EAMNS personnel also trained local African orderlies to greatly enhance the medical services in the region. A third of positions were filled by these recruits, many of whom had received Red Cross or St John’s Ambulance or equivalent training before enlistment.

Queen Alexandra’s Imperial Military Nursing Service

The Queen Alexandra’s Imperial Military Nursing Service (QAIMNS) was formed in 1902. Its remit was to provide professional nursing services to armed forces across the globe.

Though the EAMNS was established due to perceived impracticalities in supplying nursing services to East Africa, QAIMNS nurses served across the region from 1942 onwards.

Fate of the Khedive Ismail

Image: A painting of the Khedive Ismail shows the moment she catastrophically exploded (Public domain)

Image: A painting of the Khedive Ismail shows the moment she catastrophically exploded (Public domain)

On 5 February 1944, Khedive Ismail left Mombasa, Kenya, bound for Colombo, Sri Lanka with over 1,300 passengers and crew aboard.

The vessel was part of Convoy KR 8. It was the fifth time Khedive Ismail had sailed the Mombasa-Colombo route. Accompanying her were the Royal Navy warships HMS Hawkins, HMS Paladin and HMS Petard as well as four other troop ships.

The convoy had been at sea for a week when it reached waters southwest of the Maldives. The mood onboard was good with sunny skies, warm temperatures and comfortable sailing.

After lunch, roughly half the passengers took in a concert put on by the Entertainments National Service Association (ENSA). Others chose to enjoy the good weather and sunbathe on the deck.

An undersea menace

The tranquillity aboard Khedive Ismail was shattered at approximately 14.30.

An Imperial Japanese submarine, I-27, was stalking the sea near the Maldives. Soon it had Convoy KR 8 in its sights.

Submarines had been preying on Allied shipping throughout the war, and vice versa.

The Battle for the Atlantic, with Allied convoys and their escorts hunted by German U-boat ‘wolfpacks’, takes the headlines, but the Pacific and Indian Oceans were also very dangerous for shipping. Japanese submarines were a major threat to vessels here.

Aboard Khedive Ismail, a lookout managed to spot I-27’s periscope and raised the alarm.

The troopship had been outfitted with deck guns and so the gunners let fly with a fusillade aimed at the Japanese sub. Simultaneously, I-27 launched a salvo of four torpedoes, two of which struck Khedive Ismail.

Chaos erupted soon after. Khedive Ismail’s stern was engulfed by smoke and flame.

EAMNS nurse Phyllis Hutchinson was aboard Khedive when the torpedoes slammed into the ship.

As a survivor, Phyllis furnished the War Office Casualties Branch with details of the event. Her testimony paints a chaotic picture:

“I was woken up and thrown out of bed by an explosion. While I was packing myself up and wondering what had happened there was a further explosion and my cabin was darkened by a shower of water falling.

“The ship took on a sharp list to starboard… I reckon I was in the water within 15 seconds of the first explosion.”

Phyllis expanded on her experience in a further statement to the War Office:

“Miss P Cashmore somersaulted backwards into a gaping hole in the middle of the ship.

“When deep in the water, I saw the dead body of a fairly tall, slender girl shoot past me. I did not see her face but the figure was akin to that of Miss Clark Wilson.

“Miss M J Littlejohn QAIMNSR and Miss Davies QAIMNSR were sunbathing on the deck a short distance away from me prior to the attack. I did not see them again.”

The torpedoes wrought terrible destruction on Khedive Ismail. Two torpedoes hit her engine and boiler. One survivor reported leaving the main lounge where the entertainment was taking place only to open the lounge door just as the torpedo hit. The whole audience fell into the wrecked engine room below.

The boiler exploded and the ship’s superstructure was catastrophically damaged, essentially tearing Khedive Ismail in two.

Rent asunder by their impact and weakened by the inferno, she sank in just three minutes.

Many of the ship’s passengers did not have time to reach the open decks, including the roughly 1,000 soldiers of the 301st East African Regiment, and had no time to attempt an escape.

Of the souls aboard Khedive Ismail, only some 200 survived. The ship went down too fast for lifeboats to launch, although several smaller Carley floats came free. A few survivors managed to cling to the Carlies and survive.

HMS Paladin also steamed in to lower her lifeboats and pick up survivors.

The largest loss of servicewomen in a single incident in Commonwealth military history

- Queen Alexandra’s Imperial Military Nursing Service – 44 casualties

- Women's Royal Naval Service – 15 casualties

- Women's Territorial Service (East Africa) – 8 casualties

- East African Military Nursing Service – 7 casualties

The Second World War continued a process began in the Great War that challenged traditional gender roles. Many of these women had never left the United Kingdom and were taking up jobs and work not traditionally available to them.

For instance, the Wrens of the Women’s Royal Naval Service were engaged in activities such as cooking and clerking but were also wireless telegraphists, radar plotters, range assessors, electricians, mechanics and machine operators.

Although nursing was considered a traditional women’s occupation at the time, the circumstances in which these nursing sisters and matrons were serving were entirely different to peacetime.

And, of course, a large number of the casualties of Khedive Ismail’s sinking were daughters, sisters, wives and mothers.

The Second World War continued a process began in the Great War that challenged traditional gender roles. Many of these women had never left the United Kingdom and were taking up jobs and work not traditionally available to them.

For instance, the Wrens of the Women’s Royal Naval Service were engaged in activities such as cooking and clerking but were also wireless telegraphists, radar plotters, range assessors, electricians, mechanics and machine operators.

Although nursing was considered a traditional women’s occupation at the time, the circumstances in which these nursing sisters and matrons were serving were entirely different to peacetime.

And, of course, a large number of the casualties of Khedive Ismail’s sinking were daughters, sisters, wives and mothers.

Sister Grace Beecher

Much like the Khedive Ismail, Grace Beecher had a connection with Chile. She was born there to English parents in February 1896.

Aged 23, Grace emigrated to the UK via Liverpool and took up nursing. The 1921 census records Grace as working at the Royal Waterloo Hospital in London.

It seems Grace spent much of her adult life travelling between Chile and the UK, but in 1937, aged 41, she left London for the final time. Her destination was Mombasa.

Grace enlisted in the East African Military Nursing Service in July 1940, making her eligible for service both in Africa and overseas.

By 12 February 1944, Grace had been assigned to the 106 East African Section General Hospital. She was one of seven EAMNS sisters to be killed that day.

East African soldiers

In addition to the servicewomen and Royal Navy souls lost aboard the Khedive Ismail, almost 1,000 East African soldiers lost their lives that day.

The East Africa Artillery 301st Regiment was essentially wiped out in the sinking, making the event even more notable. These men there were drawn from Kenya, Uganda, and Tanzania, likely on their way to fight in Burma’s steaming jungles.

Although some may remember the war in Burma (present-day Myanmar) as fought primarily by British and Indian servicemen, large numbers of troops from across Africa served there too.

Aftermath

Image: HMS Paladin and her lifeboats were instrumental in rescuing survivors (Public domain)

As Khedive Ismail went down, the rest of the convoy scattered and proceeded onwards. The escorts HMS Paladin and Petard were detached to deal with their underwater assailant.

Paladin went forward to lower her boats and pick up any survivors. Petard engaged the now-surfaced I-27 with her deck guns. The Japanese craft then submerged again, taking refuge beneath survivors still in the water.

Petard was forced to drop three further rounds of depth charges, forcing I-27 to the surface again. A torpedo salvo from Petard struck and sank I-27 bringing an end to the attack.

With this action, Petard became the only Allied ship to sink a submarine from each of the Axis powers during the Second World War.

Despite the sinking of the Japanese submarine, not something the Japanese Navy could easily replace at this stage of the war, the loss of the Khedive Ismail was heavy indeed.

Commemorating the fallen of Khedive Ismail

The lost of Khedive Ismail are recorded across several Commonwealth War Graves Commission memorials in the UK and Kenya.

Because these casualties have no known grave but the sea, the memorials act as permanent points of remembrance and commemoration.

The majority of the servicewomen aboard Khedive Ismail are commemorated on the following CWGC UK memorials:

Brookwood 1939-1945 Memorial

Situated in Brookwood Military Cemetery, the Brookwood 1939-1945 Memorial commemorates just over 3,350 Second World War Commonwealth personnel with no known grave.

44 of those on its name panels are the sisters of the Queen Alexandra’s Imperial Military Nursing Service.

Chatham, Plymouth & Portsmouth Naval Memorials

The naval memorials at Chatham, Plymouth and Portsmouth are some of the largest memorials maintained by Commonwealth War Graves.

Together they commemorate more than 45,600 Royal Navy personnel lost on operations across the world’s oceans, over 41,000 of which are Second World War casualties.

The women of the WRNS lost on Khedive Ismail are amongst those commemorated on these three naval memorials.

East Africa Memorial

On the name panels of the East Africa Memorial are carefully rendered the names of more than 2,200 East African personnel of the Second World War.

The memorial, which is situated in Nairobi War Cemetery, Kenya, mostly commemorates those with no known war grave lost on operations in Italian Somaliland and Ethiopia.

However, over 660 names come from the 301st East African Regiment aboard the Khedive Ismail when she was sunk. The nurses of the East African Military Nursing Service lost in the sinking are commemorated alongside them.

Can you share their stories? Do so on For Evermore

For Evermore: Stories of the Fallen is our online resource for sharing the memories of the Commonwealth’s war dead.

It’s open to the public to share their family histories and the tales of the service people commemorated by Commonwealth War Graves so that we may preserve their legacies beyond just a name on a headstone or a memorial.

If you have a story of someone we commemorate who died in the sinking of Khedive Ismail, or any of the servicemen and women in our care, we’d love to hear it! Head to For Evermore to upload and share it for all the world to see.